Could Obama, Iran's Rouhani meet 'accidentally' at the UN next week?

The Iranian government has conveyed a tone of compromise and reason ahead of centrist President Rouhani's first visit to the UN.

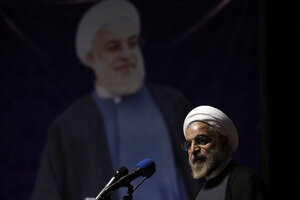

Iranian President Hasan Rouhani delivers a speech during his campaign for the presidential election in Tehran in May. The U.N. has slotted the new moderate-leaning president to address the global gathering of leaders on Sept. 24 - just hours after US President Barack Obama is scheduled to wrap up his speech.

Vahid Salemi/AP

Washington

Editor's note: This story was updated to include White House comment released after publication.

Signs are plentiful and growing that Iran and the United States are preparing to take advantage of the recent election of a centrist president in Tehran to break a logjam in stalled nuclear talks and ease a generation of mutual hostility.

From public statements to official Twitter feeds and Facebook pages, Iran’s government has launched a campaign to portray a tone of reason and compromise on issues ranging from Holocaust denial to resolving the nuclear standoff.

Iran’s new President Hassan Rouhani affirmed last Friday Iran's bedrock position that it must keep its nuclear program to produce electricity, but called for new steps in stalled negotiations: “We want the swiftest solution to [the nuclear impasse] within international norms.” Likewise, Iran's nuclear chief Ali Akbar Salehi on Monday told the UN's nuclear watchdog agency in Vienna that Iran was determined to end the nuclear dispute, saying: "This time we are coming with a more full-fledged … desire for this."

The contrast with years of combative rhetoric that defined Iran’s former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad could not be sharper.

There has already been an unprecedented exchange of letters between US President Obama and Rouhani. Mr. Obama told ABC News he had “reached out” to his Iranian counterpart, saying that Iran might play a role in solving the Syria crisis and prompting speculation that Obama and Rouhani might “accidentally” bump into each other during the UN General Assembly in New York next week. If it happens, it will be the first direct interaction between the two country's presidents since Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution prompted a bitter break in relations.

A White House official said today that Obama has no plans to meet with the Iranian leader, but did not entirely rule out the possibility.

The previous Iranian negotiating team “wasn’t genuinely interested in making a nuclear deal,” says Robert Einhorn, who until last May was the US Department of State’s special adviser for nonproliferation and arms control, and a member of the US nuclear negotiating team. They were “ideologically indisposed” to finding an accommodation with the West, hindered by “total self-delusion” about the impact of sanctions and US and Western resolve, and they “resisted all compromise.”

“This new leadership is very, very different,” says Mr. Einhorn, now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, speaking in recent days at the Atlantic Council think tank in Washington. He described Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif – who will handle the Iranian side of the talks – as one of the best diplomats he had “ever seen."

“They are realistic, they’re pragmatic, they have no illusions about the economic predicament they are in," Einhorn says.

A framework forms

Analysts say that contours of a nuclear deal to permanently cap Iran's nuclear program are increasingly clear, but that perennial stumbling blocks remain. The goal of world powers is to structure Iran's program so that it can produce only energy, not nuclear weapons. Iran insists its program is solely for peaceful purposes.

Iran has signaled a willingness to curb its most sensitive nuclear work – uranium enrichment to 20 percent purity, which is a few technical steps from bomb-grade – and accept far more intrusive inspections and monitoring. In return, Iran expects the US and other world powers it is negotiating with (known as the P5+1, with Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany) to substantially ease sanctions that have crippled Iran's economy, and to recognize Iran's "right" to enrich uranium for peaceful purposes.

“I’m optimistic about a resolution on the nuclear program because what we want is not fundamentally different from what the international community wants… for Iran’s nuclear program to not be diverted towards weaponization,” says Nasser Hadian-Jazy, an international relations expert at Tehran University who is familiar with the thinking of Iran's new government, in an interview.

He says Iran is ready to embrace a “robust” verification system, resolve outstanding issues of past weapons-related work, and perhaps eventually cut back the number of centrifuges currently installed to enrich uranium from the current 18,000-plus.

While Iran's sprawling enrichment complex at Natanz will likely be on the table, Hadian-Jazy says that the smaller, deeply buried enrichment facility at Fordow – which is virtually impregnable to US or Israeli airstrikes, and has been a key focus of the P5+1 at nuclear talks – will not be up for discussion. And if Iran is willing to scale back the number of operating centrifuges, it will not likely accept limits on improving the technical capacity of those those centrifuges that remain.

"There are red lines," says Hadian-Jazy. “This is the endgame I am talking about. Don’t expect [the Iran team] to go there and say that, ‘Yes, we are ready to cut the number of centrifuges.’ But at the end I believe that is possible,” he says.

What's 'acceptable'?

What is not yet clear is how Iran's red lines can gel with those of the US and P5+1 at the negotiating table, and if they will be enough. US officials have long said that "all options," including military force, were "on the table" in dealing with Iran, and in the ABC interview, Obama cautioned Iran not to read too much into the US-Russia deal over Syria’s chemical weapons, which averted US military strikes while agreeing to dispose of all of Syria’s chemical arms.

"They shouldn't draw a lesson that we haven't struck [Syria], to think we won't strike Iran," Obama said. "On the other hand, what they should draw from this lesson is that there is the potential of resolving these issues diplomatically."

Dispute over what both Iran and the US consider an “acceptable” form of Iran’s nuclear program have overshadowed multiple rounds of talks since early last year in Istanbul, Baghdad, Moscow, and Kazakhstan.

But the US goal to limit Iran’s breakout capability to race secretly for a bomb – entailing limitations on the number and types of centrifuges, and the size and quality of Iran’s stockpiles of enriched uranium – is such that, “to be acceptable, any enrichment capability in Iran would require much greater restriction than – so far, at least – even Iran’s new leadership is prepared to concede,” says former US official Einhorn.

New spirit of compromise

Can that form the basis of progress? Obama may have more executive leeway to sweeten the deal with sanctions relief than commonly thought, says Kenneth Katzman, a Persian Gulf specialist for the Congressional Research Service. He may be able to quickly ease some US measures in the course of a negotiating process, despite tough and time-consuming standards required by Congress to remove some sanctions entirely.

“The Iranian people need to understand sanctions would not be erased in one day, true,” said Mr. Katzman, speaking at the Atlantic Council. “But if you look at the way the sanctions work, the president, the executive branch, still has a lot of discretion about how to apply the sanctions.”

Banking on that – and buoyed by the high expectations of a new negotiating team and political reality in Iran since the shock June election of Rouhani – the Iranians have sought to show themselves as ready to deal.

“We should not expect Rouhani to perform miracles, but there is a good chance he sets Iran back on a sensible course,” said Haleh Esfandiari, director of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center, also speaking at the Atlantic Council.

“Both at home and abroad, [Rouhani] knows that politics and diplomacy involve compromise, a word that did not exist in the last eight years in the political jargon of Iran’s foreign policy,” says Ms. Esfandiari. “He knows what concessions he can secure, and what concessions he has to make.”