Justice Dept. vows to strike harder against hackers, nations behind cyberattacks

John Carlin, chief of the Justice Department’s National Security Division, says the US needs to raise the stakes for cyberattacks on the US: If the cost of stealing information from American companies results in swift criminal action or sanctions, hackers may eventually decide it's not worth it.

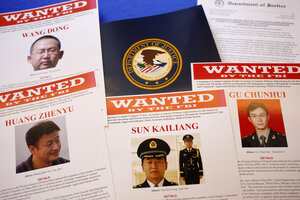

Last year, the Justice Department charged five Chinese hackers with economic espionage and trade secret theft in the first-of-its-kind case involving international cyberespionage case.

Charles Dharapak/AP/File

The US government has ramped up efforts in recent months to hold hackers and nations behind cyberattacks on American companies more accountable.

After the Sony Pictures attack, the US pinned blame on North Korea and responded with sanctions. Last year, the government publicly indicted a group of Chinese military hackers for economic espionage against prominent American companies including US Steel Corp. and Westinghouse.

At the center of these responses is John Carlin, the assistant attorney general for National Security. “We’re not giving out any free passes,” he told Passcode.

Mr. Carlin’s promise to punish countries engaged in digital spying on American companies is part of an emerging, broader US government strategy. Charging those responsible for cyberespionage until recent years was an incredibly difficult prospect for the US government, which treated nation-state attacks on companies to steal trade secrets or plots for major cyberattacks on the country exclusively as an intelligence matter. The cases were essentially decriminalized by default.

That started to change around 2012, when the Justice Department’s national security division expanded its focus beyond more traditional counterterrorism threats to cyberthreats, growing teams of specially trained lawyers to investigate and prosecute digital attacks. The national security division was trained on handling cyber cases, and every one of the 93 US attorneys’ office gained at least one prosecutor trained to deal with cyberespionage.

Now, Carlin is widening the aperture. “We’re not wedded to criminal prosecution. It shouldn’t have been off the table because it should be a tool in the toolbox, but the goal here has to be threat driven: To stop the activity, to protect our companies from having their intellectual property stolen, protect our infrastructure from a terrorist attack,” Carlin said. The right response to a cyberattack, Carlin said, “might mean using sanctions, it might mean designating an entity, it might mean working with the State Department on how to do that diplomatically.”

Passcode sat down with Carlin to discuss the department’s approach. Edited excerpts follow.

Passcode: What are some examples of the Justice Department stepping up its efforts?

Carlin: One is the [People’s Liberation Army] case. That [indictment last year] showed we can find who’s behind the keyboard, we can do it with great detail, and when we do it, we’re not afraid of then taking the next step of attempting to hold them responsible for their actions when they’re stealing information from American companies.

Secondly, you saw in the Sony case another example of tackling something as a national security problem. In that instance, doing attribution very quickly, making the decision to then publicly state that we know who did it, and this is who did it, and follow up with sanction activity. We’d talked in theory about how we were going to apply these two approaches, and I think last year was a watershed in seeing it applied twice.

Passcode: Now that Justice has the resources, how does that ramp up the pressure to actually hold people responsible?

Carlin: We’re going to look to determine when you see a significant intrusion, whether it’s the theft of information from an American private company that’s going to be used against them by a competitor, or the destruction of data. We need to follow the evidence and information where it leads. We’re not giving out any free passes ahead of time. If it leads to someone who’s in a criminal group overseas, an organized criminal group in eastern Europe, we’re going to work to use our criminal tools and hold that person to account. If it turns out they’re a nation-state actor, we’re going to look to hold them to account as well.

Passcode: But probably those Chinese military hackers won’t see the inside of a courtroom here. And with North Korea, the US increased sanctions on a country that already has a lot of sanctions in place. Do you see any of these responses as being able to really deter potential hackers, or will the responses escalate if the behavior doesn’t stop?

Carlin: What we need to do is continue as a country to get better at the attribution and determining who did it. Showing that when we can figure it out, we’re going to say who did it. Because that in itself is a form of deterrence. And we need to keep increasing the costs of stealing information from US companies to use it against them for economic advantage, until those who are doing it decide it’s not worth [it].

If what we’ve done to date doesn’t work, we’re going to need to keep doing it and keep applying that pressure until the costs outweigh the benefits. That’s how you change people’s behavior.

Passcode: How does attribution play into this? Some people in the information security community were skeptical about the speed at which the administration put the blame on North Korea for the Sony attack.

Carlin: The abilities of the community writ large – both law enforcement, intelligence, and others – to analyze cyberevents and figure out who did it have improved exponentially since, say, a decade ago … including [creating] things like the National Cyber Investigative Joint Task Force [at the FBI]. With that came a realization, ‘Boy, certain countries are stealing a whole lot of information from our companies, we’d better do something about it.’ Applying that same apparatus – and not just doing the intelligence collection, but getting that information into a form you can use to do attribution – is an area you’re going to need to continue investing resources. So much of this [information] is in private hands, so we’re going to need to increase the cooperation.

Passcode: What are some ways to do that?

Carlin: Get US attorneys out there in the community, meeting with the companies, particularly the C-suites and general counsels, developing relationships of trust so that when incidents occur they share the relevant threat information and give a context as to why someone would be doing this, why would they be stealing this, why would they be attacking you.

Passcode: President Obama is pushing his cyberthreat information sharing plan pretty hard. Would that actually prevent major attacks?

Carlin: With or without it, we’re working on some of these. In particular that legislation would help companies share information within sectors in a way where they didn’t worry about potential legal liability for sharing the information, to better share the information to figure out what they’re seeing in the sector and share threat indicators with the government … . Legislation that says, ‘If you do this type of activity, you will be immune,’ is what most of them want to be able to share the information.

Passcode: What about from the privacy side? Some privacy advocates are concerned about the immunity and sharing people’s information with the government.

Carlin: You always need to be concerned, and at the DOJ we’re about making sure that on the one hand, we’re protecting people from legitimate national security threats, including the theft and loss of private sector information– and [we’re] doing so under respect for the law.

Passcode: Where does Justice fit into this newly announced Cyber Threat Intelligence Integration Center?

Carlin: Having a center that focuses on having a coordinated view across the community helps us in our policy role. When we sit at the National Security Council it helps us in doing the training, and feeding US prosecutors across the field, and could help us in a specific case where they tie together different threads and say, ‘Here’s the bad actor, and here’s what their conduct looks like, so if you see this type of intrusion occur at a facility this is the likely attribution.’

Passcode: So let’s go back to Sony. If it were up and running at that time, how would the national information sharing center center have affected the government’s response?

Carlin: I think one thing we realized in responding to Sony is that we were able to put that together ad hoc with very capable work and under the leadership of the FBI, but we didn’t have a standing group that put together that type of cross community assessment on particular incidents – and it’d be good if we had one.

Passcode: The Sony attack was distinctive because it was not just an attack that stole data, but destroyed computers and servers. And it was considered an attack on free speech, as a coercive means to prevent the showing of the movie “The Interview.” Are we going to see more of this?

Carlin: I think we’ll see more of everything. We’ve put almost everything we value into cyberspace. It’s where your systems run, it’s where we store what we value most, it’s where your kids play. Every type of crime, threat that we’ve seen is just moving into cyberspace.

Passcode: Do you think a terrorist group is going to carry out some big catastrophic attack down the line?

Carlin: They’ve announced their desire to cause a catastrophic cyberattack. Terrorists often say what it is they’re willing to do; we’ve got to listen carefully and take the necessary steps. There are steps that we can take to make sure we’re effectively sharing and integrating information and intelligence and therefore act on it to disrupt threats.