Your Internet router is a security risk. Here's why

Not only are many home and small office routers sold with security vulnerabilities, the devices are often difficult for users to update and easy for hackers to penetrate.

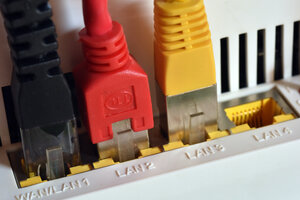

AP/File

BERLIN

Over the past year, a team of hackers invaded more than 100,000 home routers around the world, gaining access to the devices through weak and default passwords.

But they weren't out to swipe users' personal information or infect computers with malicious software. Quite the opposite. They set out to rid insecure routers of malware and in the process make them safer.

The vigilante techies, who recently revealed themselves as the White Team when they published their source code on GitLab, developed their Linux.Wifatch software in part to prove how easy it is to compromise small office and home routers.

Security researchers have long warned that home and office routers can be a malicious hacker's entryway into a computer system. But router security has long been overlooked or ignored by consumers and manufactures alike. Making matters worse, the router is often the last piece of hardware that is updated or replaced, as it’s often hidden away and forgotten in cabinets and closets.

Yet, these devices act as gateways between an individual or businesses' devices and the Internet, making them crucial components in even the smallest home networks. When routers are compromised or aren't secure, malicious hackers can infect them with malware, reengineer routers to direct user to spam sites, or take them over for use in distributed denial of service, or DDoS, attacks to overwhelm targets' networks with Web traffic.

"There are routers that have spent years on the market and haven’t seen a single security update," says Jan-Peter Kleinhans, program manager of the European Digital Agenda Program at the stiftung neue verantwortung (New Responsibility Foundation) in Berlin.

What's more, says Michael Horowitz, a computing expert who launched RouterSecurity.org earlier this year, consumer-grade routers are attractive targets to criminal hackers because they are passing along any information from within a home network 24-hours a day. As a result, many criminal hackers use technology that can constantly scan nearby routers, looking for default passwords and other vulnerabilities.

The problems with routers is so widespread that nearly 75 percent of Amazon's top 50 best-selling home and small office routers have security vulnerabilities, according to research in 2014 by software company Tripwire.

"A lot of devices are rushed out to the marketplace without having proper security vetting," says Craig Young, a Tripwire security researcher. "Companies that are making them don’t always have people with security expertise – they don’t always think, 'What if somebody tries to use this by giving it input that we’re not expecting.' "

One common flaw lies within the diagnostic functions of most routers. Users are typically able to test their routers' Internet connectivity, but that ability can let others take remote control of the device, too, says Mr. Young.

Adding to the risk, 46 percent of consumers and 30 percent of technology professionals do not change their routers' passwords from its default, according to the Tripwire report.

"People should be thinking about routers the same way they would think about their computers,” says Young. "If you’re not periodically updating them and doing basic hygiene steps, then bad things are going to happen."

A compromised router could, for example, allow digital intruders to redirect users to fake bank sites designed to steal financial information. In 2014, the cybersecurity firm Team Cymru discovered such an attack on some 300,000 SOHO routers manufactured by companies such as D-Link and Tenda.

Consumers often put convenience ahead of security when it comes to their routers, says Mr. Horowitz of RouterSecurity. Many want functions such as Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) that allows devices in a network to interact with each other, but punches a hole in the firewall, he says.

What's more, says Mr. Kleinhans of the European Digital Agenda Program, consumers typically do not demand security updates for their routers. As a result, most manufacturers are not motivated to provide them.

He hopes that will soon change in Germany, where the Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) recently published a set of criteria for manufacturers to improve router security.

The level of router security does varies from one make to another, as the majority of router software isn't open source, says Tony Lee, the technical director at the security firm FireEye. Yet there are a number of projects that allow users to replace the commercially shipped firmware with an open-source alternative, says Mr. Lee.

"With open-source firmware you are trusting a larger community of developers that often includes security experts," he wrote in an e-mail. "But most importantly, the end user has the option of performing their own code review and security checks – provided they have the desire and skill set."