Influencers: Antihacking law obstructs security research

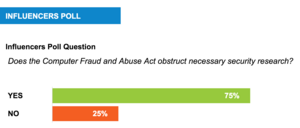

A strong 75 percent majority of Passcode’s Influencers said a US government law used to prosecute hackers overly restricts necessary security research.

Illustration by Jake Turcotte

A strong 75 percent majority of Passcode’s Influencers said a US government law used to prosecute hackers overly restricts necessary security research.

Passcode’s group of digital security and privacy experts say the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) – meant to prevent illicit trespassing on computer systems – is written far too broadly and often results in punishments that are too harsh for the infractions. They complain the law’s vague language enables prosecutors to go after legitimate security researchers investigating potentially dangerous security vulnerabilities that could harm consumers – and even target users of video streaming services such as Netflix and HBO Go who share their passwords with friends and family.

“You could indict a ham sandwich with the CFAA,” says Jeff Moss, founder of the DEF CON and Black Hat hacker conferences, in response to the Passcode’s Influencers Poll, a regular survey of more than 150 leading voices from the government, defense, private sector, and advocacy communities.

The law allows for “intimidation by companies of lone researchers,” Mr. Moss says, and needs to be updated to “reflect the current reality of what consent means in a hyperconnected and always-on world.”

While some tech companies have started so-called “bug bounty” programs to allow and even incentivize hackers to legally search for security flaws, others have opted to use the CFAA to prosecute researchers whose findings they feel overstepped terms of service or accessed their databases improperly. For instance, in May, the FBI arrested Texas-based security researcher Justin Shafer after he discovered a vulnerability in dental software that could allow anyone to view sensitive data for 22,000 patients on a publicly available server. The company that developed that software said Mr. Shafer’s decision to access that data violated the CFAA – even though it was meant to root out vulnerabilities that could endanger consumers.

The law specifically bans “unauthorized access” to computer systems, but Influencers say it doesn’t clearly define what that means. “The vagueness of ‘unauthorized access’ makes researchers gun shy when their research requires interacting with systems and services exposed to the public internet,” says Chris Wysopal, chief technology officer at the cybersecurity firm Veracode.

And if researchers are unable to investigate technical flaws, everyone’s security is at stake, Mr. Wysopal adds. “This stifles our understanding of the risks present in the technology and the way we use the internet.”

Researchers’ roles are vital to consumers, adds Rodney Joffe, a senior vice president at the analytics firm Neustar, yet the law “has repeatedly stymied solutions that could have mitigated the damage caused by criminals and nation-state actors. And it has done nothing to reduce these malicious activities.”

The “overzealousness” of attorneys who prosecute CFAA cases is another thing that can deter security researchers, adds Cris Thomas, a strategist at Tenable Network Security also known by the hacker name Space Rogue. The case of famed programmer Aaron Swartz, who committed suicide in 2013 while facing 35 years in prison and a $1 million fine on federal data theft charges for leaking millions of documents from behind the paywall of an academic database to the public internet, drew public attention to the tough penalties.

Christopher Doggett, a senior vice president at the data backup company Carbonite, also cites reports that members of US law enforcement have threatened security researchers with indictment in response to their efforts to discover vulnerabilities. “When these considerations are combined with the fact that the statute can result in multiple redundant felony counts with high penalties, there can be almost no doubt that the ‘white hats’ and ‘grey hats’ in the security community have a very real reason to be concerned,” Mr. Doggett says. “And that in turn can mean only one thing: fewer vulnerabilities are discovered and disclosed by those who seek to make the online world a safer place.”

The broad legal boundaries of the CFAA have also allowed prosecutions of computer crimes to proceed if hackers are found to have violated a website’s terms-of-service agreement, some Influencers say. “That overreading should be soundly rejected,” says Jonathan Zittrain, a professor at Harvard Law School.

In fact, linking violations of terms of service to computer fraud and abuse might not be so easy if a recent court challenge is successful. Last month, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit claiming the CFAA violates the constitutional right to free speech on behalf of a group of academics and journalists from several universities and First Look Media, which publishes The Intercept. The researchers complained overly restrictive terms of service on websites they needed to use for an investigation racial discrimination in housing and employment prohibited them from scraping data that was otherwise publicly available.

Just this week, that case may have gotten a boost when the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in a separate case that violating the terms of service for a website can’t be the sole basis for prosecuting cases under the CFAA.

Originally signed into law by President Reagan as part of a 1984 revision of the US criminal code, there has already been motion in Congress to update the law. For instance, Sen. Ron Wyden (D) of Oregon and Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D) of California unsuccessfully pushed for legislation last year that would clarify vague language in the law to help low-level hackers.

Some of Passcode’s Influencers are in a position to push for change on Capitol Hill. “The vital role security researchers play in protecting our systems today was certainly not anticipated by the drafters of the CFAA, and while the Justice Department has been making strides in communicating with researchers about their prosecutorial discretion, it is clear that the language of the statute is chilling research,” says Rep. Jim Langevin (D) of Rhode Island. “It is clear that the CFAA is in need of updating thanks to rapid advances in technology and cybersecurity practices.”

Still, Mr. Langevin stressed that “any reform of the CFAA must ensure that we possess the necessary tools – such as botnet provisions – to prosecute the many malicious actors who attack US networks each day.”

On the other side, a 25 percent minority of Influencers said that changes to the law are not necessary, since they see many violations as fairly clear-cut.

“Doing ‘research’ on a network without the network owner’s permission is a highly questionable practice,” said Stewart Baker, a former National Security Agency counsel who currently serves as a partner at the Washington-based law firm Steptoe & Johnson. “One person’s researcher is another person’s hacker,” added an Influencer who chose to remain anonymous. Influencers are given the choice of responding on record or anonymously to preserve the candor of their responses.

Others think that legitimate security researchers haven’t been seriously held back by the CFAA, while, at the same time, pushing changes passed through Congress could prove particularly difficult. “Sure, there are aspects of it that could be improved, but the security research community isn’t really one to be held back by laws,” said one Influencer. “I think it’s doing pretty well – and trying to make changes to it would take a lot of political capital out of a Congress that doesn’t seem able to do much of anything of value.”

What do you think? VOTE in the readers’ version of the Passcode Influencers Poll.

Who are the Passcode Influencers? For a full list, check out our interactive masthead here.

Comments:

YES

“In its current form, the 1984 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act is too broad and needs clarification in scope on activities that can hamper legitimate security research. There is pending bipartisan legislation in Congress would exclude terms of service violations from the Act. The Act is important in the rapidly changing digital economy, especially for combating cyber crime, and specifically identity theft. But like technology itself, it needs to be updated and adapted to the newest and most critical threats while achieving a balance of security, commerce and privacy.” – Charles (Chuck) Brooks, Sutherland Global Services

“The CFAA needs to be ‘modernized’ - blanket declaration of criminal activity when someone violates a website’s Terms of Service is just too broad.” – John Pescatore, SANS Institute

“But it is increasingly important to have a sense of how much it does so. Almost any conceivable regulation will restrict, intentionally or otherwise, some kinds of research (and this is true not just of IT). Not all those restrictions are bad; some are justified on the basis of a benefit-risk analysis. But how are we to know if any particular restriction is ‘worth it’? The ‘chilling effect’ arguments are often theoretical and unmeasured. Time to get more precise.” – Steve Weber, UC Berkeley

“Many researchers fear that the onerous terms of service of internet sites may trigger the Act through basic security research, or even by mistake. Now that the [Defense Department] has offered a bug bounty for testing the security of their sites and systems, the legal landscape becomes even more confusing.” – Günter Ollmann, Vectra Networks

“Obstruct may not be the right word but there is definitely a chilling effect on security research because of poorly worded provisions in the CFAA. Fear of criminal prosecution has forced many researchers to reconsider their actions leaving the public at risk. The problem isn’t limited to just the ambiguities and vagueness in the wording of the CFAA but also in overzealousness of prosecuting attorneys. Companies who threaten civil litigation are also a major problem and use the threat of the CFAA to force researchers and the companies they work for to bend to their demands.” – Cris Thomas aka Space Rogue, Tenable Network Security

“The CFAA is well-intended but out-dated. It has only been amended a handful of times since it was first passed in 1984, while the technology landscape has changed utterly over those thirty years.” – Nate Fick, Endgame

“The CFAA plays an important role in society but has been applied beyond its original intent to the detriment of legitimate security research. The [Justice Department] could play a constructive role here by providing thought leadership to fellow prosecutors on the appropriate parameters to be applied in CFAA cases involving security researchers.” – Abigail Slater, The Internet Association

“The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act is long overdue for reform. Sometimes, important security issues can be uncovered by poking at a product or service in a way that the manufacturer never intended. Unfortunately, the CFAA criminalizes unauthorized poking by default, even if there is no intent to do harm. This certainly deters valuable security research and provides a cudgel that providers have used to silence critics rather than respond to the underlying problems they are identifying. It certainly behooves service providers to explicitly authorize responsible security research on their products. Even the Pentagon explicitly authorizes security research of their systems and networks. However, Congress should act by heightening the mens rea requirement for prosecution under the CFAA. The balance that was struck in the 1980’s is no longer relevant today.” – Tom Cross, Drawbridge Networks

“The CFAA - a statute suffering from both definitional ambiguities and circuit splits - is, unfortunately, a part of the standard tool-kit of legal threats aggressive attorneys sometimes use to silence researchers attempting to report security vulnerabilities to companies.” – Andrea Matwyshyn, Northeastern University

“The framers and authors of CFAA never could have imagined the kind of cutting edge offensive computing research that is commonplace today. The vagueness that makes it so effective against today’s cyber-crime is a double-edged sword when it comes to the risk security researchers must subject themselves to just to do their job. And by using CFAA as a litmus test, legislators who don’t understand the inherent nuance are likely to ban huge swaths of necessary security research, with the misguided intent of ‘fixing’ cyber security.” – Nick Selby, Street Cred Software

“The ‘elasticity’ that the Justice Department has read into the CFAA allows them to go after a range of well-meaning behavior. That’s obviously going to have a chilling effect on researchers. The problem then becomes deciding how you draw lines between legitimate researchers and ‘intruders.’ The bad guys don’t wear burglars’ masks anymore.” – Influencer

“In its current form, the CFAA is written with such broad terms that it makes it possible for prosecutors to use it in an extremely wide range of scenarios, which poses a real threat to all types of security researchers at any time. And the risk is not theoretical, precedents have already been set in a notable cases such as United States v. Auernheimer and United States vs. Swartz, to name two. In addition, there have been reports that members of U.S. law enforcement have threatened security researchers with indictment in response to their efforts to discover vulnerabilities. When these considerations are combined with the fact that the statute can result in multiple redundant felony counts with high penalties, there can be almost no doubt that the ‘white hats’ and ‘grey hats’ in the security community have a very real reason to be concerned. And that in turn can mean only one thing: fewer vulnerabilities are discovered and disclosed by those who seek to make the online world a safer place.” – Christopher Doggett, Carbonite

“As technology has evolved so must the law. CFAA should be updated so the research community can improve cybersecurity without fear of prosecution.” – Influencer

“Numerous security researchers have pointed out the overbroad nature of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. With so many technologists voicing concerns about CFAA’s impact on the field, only the woefully ignorant would suppose that it has no detrimental impact on security research. As should be obvious, even if the intent of CFAA isn’t to limit security research, the self-censorship within this field that has been caused by CFAA is already creating a detrimental wake.” – Sascha Meinrath, The X Lab

“We have been trying to reform this for a long time.” – Nico Sell, Wickr

“Actually, current interpretations of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act are probably more materially obstructing computer security research than the CFAA. That having been said, there is a history of private sector actors invoking the CFAA and leveraging the power of government to respond to a wide variety of activities that don’t necessarily appear malicious.” – Bob Stratton, Mach 37

NO

“Sure, there are aspects of it that could be improved, but the security research community isn’t really one to be held back by laws. And they seem to be crushing it in some many ways. I think it’s doing pretty well - and trying to make changes to it would take a lot of political capital out of a Congress that doesn’t seem able to do much of anything of value, so I’d rather they focus on ISIS and climate change than try to spend time working on this issue.” – Influencer

“Doing ‘research’ on a network without the network owner’s permission is a highly questionable practice.” – Stewart Baker, Steptoe & Johnson

“One person’s researcher is another person’s hacker.” – Anonymous Influencer

“No. But it does obstruct information sharing.” – Dan Geer, In-Q-Tel

What do you think? VOTE in the readers’ version of the Passcode Influencers Poll.