Why I make my kids read privacy policies

It's like teaching them to look both ways before crossing the street. Reading privacy policies for apps is about learning basic safety tips in the Internet Age and gives parents an opportunity to teach kids about responsibility and self awareness on the Web.

A student looks at his smartphone between classes at the Cuyama Valley High School in New Cuyama, Calif.

Christine Armario/AP

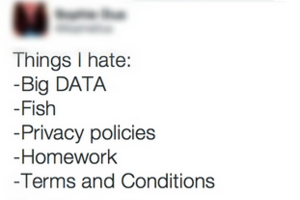

In her first public tweet, my teenager vented her top most-hated things:

Behold the tempest of teen rebellion in our house.

Put aside her dislike of seafood and homework for the moment. To fully appreciate the list, you should know that I – the mom – am a lawyer. In fact, I am a lawyer who has been helping Internet companies write privacy policies and terms of service and generally navigate global regulations for almost 20 years. More recently, I served as President Obama’s Deputy Chief Technology Officer focused on Internet, privacy (yes, including big data), and innovation.

My teen’s particular dislike of privacy policies is borne of our household rules for accessing Web services or downloading new mobile applications. We have three basic rules:

- You have to read the privacy policy before you create an account or download an app.

- You have to explain to Mom what gets shared and with whom.

- Mom and Dad have final say.

My kids hate these rules.

Yes, I know that most of the population doesn't read the small print of privacy policies. It makes their eyes glaze over. I don’t love privacy policies either, notwithstanding the fact that I have drafted scores of them over the years.

But teaching kids to read a privacy policy is like teaching them to look both ways before they cross the street. It’s a basic safety rule that instills both caution and judgment. Whether you are helping your younger child set up a kid’s account or talking with your teen about what’s on her ever-present phone, the privacy policy opens an opportunity for both of you to talk about what they may encounter online.

My kids have learned to look for the few things that I always ask about.

- Who is offering the service? Is it a company that we’ve heard of? Are they well rated? Where are they located and how do we get in touch with them?

- What information is collected? Do you have to give them anything other than an e-mail address? Are there photos? What kinds of information does the app access (contact lists? camera? GPS location?) and why?

- What information is shared? Is your information public? Can it be made private only? Do any third parties have access to your information?

These rules actually aren’t very different from what we teach kids in the real world.

Stranger danger

As a parent, when I ask who offers the service or who has access to the information, I basically want to know – and want the kids to learn – if this is a service that we can trust. There are signs of dangerous apps, just like there are characteristics in people to avoid. If an app doesn’t have a privacy policy or doesn’t provide contact information, the developers are either inexperienced, sloppy, or hiding something. If anything about a service is unexpected, weird or scary, I want the kids to find me or another trusted adult. Just like teaching your kids to be wary of strangers, we need to teach them to be wary of new apps when they engage with them.

Watch your stuff

Data is valuable and we should protect it in the same way that we protect our wallets, our bags, and our teddy bears. When I ask my kids about what data is collected and who can access it, I am asking them to think about what is valuable and what they are prepared to share or lose. I want them to be careful when they post pictures of themselves or their friends. Of course, we give up some data when we use online services. The point is that we should do so thoughtfully and with care.

Buckle up

Even when we share our personal information, we still have ways to safeguard it (at least with responsible developers). My kids generally have locked accounts, meaning that only people they actually know offline can see their stuff online. (The teenager got to go public on Twitter just recently, and you see how that’s gone.) We usually don’t download apps that share data with third parties unless there’s minimal personal information shared or good privacy controls. We look for options to terminate and uninstall an app in case we don’t like them. None of this ensures perfect privacy or safety, but the kids are developing the habits of precaution, just like buckling their seat belts in the car.

My kids may hate privacy policies and terms of service, but they know that we are a family of technology and data optimists, too. We want them to be comfortable, competent, and safe online with the tools to make good choices. Dealing with teenage snark is a separate lesson.

Nicole Wong previously served as US Deputy Chief Technology Officer in the Obama administration, legal director at Twitter, and vice president and deputy general counsel at Google. She is a founding columnist for Passcode, the new section on security and privacy at The Christian Science Monitor, and a mother of two Internet-savvy kids. Follow her on Twitter @NicoleWong.