Opinion: Why trade secrets bill will deter cybercrime

The Defend Trade Secrets Act is another sign that the US government is finally acknowledging that an active deterrence must be a key part of any successful cybersecurity plan.

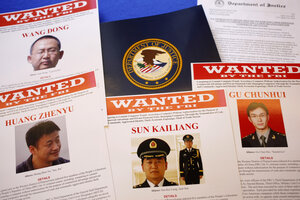

For the first time in May 2014, a US grand jury charged Chinese military officials with economic espionage and trade secret theft.

Charles Dharapak/AP/File

In a major step toward deterring cybercrime, the Senate unanimously passed a bill Monday to empower corporate espionage victims to seek damages for computer-enabled intellectual property theft.

The Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA) is yet another sign of the US government's growing commitment to deterrence as a key element in the country's cybersecurity strategy. By enabling corporate victims to recover losses from cyberenabled IP theft, the bill encourages victims to pursue perpetrators.

The bill is designed to make cyberespionage more costly for malicious hackers – either acting alone or backed by nation-states – by allowing victims the chance to recover significant monetary damages after an attack.

Until recently the dominant approach to cybersecurity in the US was to batten down the hatches. We almost exclusively focused on reducing our vulnerability to cyberattack and espionage.

This approach didn’t work. Adversaries continue to wage successful cyberespionage campaigns despite concerted long-term US efforts to bolster network defenses. The lesson learned: Stronger locks and taller fences by themselves are not enough to stop targeted attacks. That’s why deterrence is key.

One of the first public indications that the US government was embracing threat deterrence came in May 2014, when the Department of Justice indicted five Chinese military officers for economic espionage against US companies including Westinghouse Electric and US Steel.

By identifying the Chinese PLA officers involved and providing details of their activities – i.e., by "naming and shaming" the perpetrators – the US sought to deter the activities by increasing the political and diplomatic costs of engaging therein.

The US response to the Sony hack also reflected a shift toward cyberthreat deterrence. Not only did the FBI attribute the hack to the North Korean government, but also President Obama signed an executive order which enabled the Treasury Department to impose targeted sanctions on North Korean agencies and 10 government officials.

That was the first time that the US retaliated for a cyberattack perpetrated against a private company – and the first time that sanctions were used in response to a nation-state sponsored cyberattack. Given the limited extent of US engagement with North Korea, the sanctions – which bar certain commercial relationships – have had a minimal effect.

Still, the US sent a strong signal to other would-be digital adversaries that those sorts of attacks wouldn't be tolerated. As Treasury Secretary Jack Lew said at the time, “These steps underscore that we will employ a broad set of tools to defend US businesses and citizens, and to respond to attempts to undermine our values or threaten the national security of the United States."

In April 2015, just months after imposing targeted sanctions on North Korea, Mr. Obama issued an executive order establishing a cyber sanctions program modeled on US counterterrorism and nonproliferation sanctions programs.

The cyber sanctions program is designed to penalize those who engage in destructive digital attacks against critical infrastructure and/or engage in commercial cyberespionage. Specifically, it authorizes the US government to freeze assets of foreign nationals responsible for "malicious, cyberenabled activities."

Now, the Defend Trade Secrets Act is meant to create a private right of action for trade secret misappropriation. As soon as the bill becomes law – it's likely to pass the House and the Obama administration supports it – companies should take action and pursue violators. Going after malicious hackers is key to deterring cybercrime over the long run.

Melanie Teplinsky teaches information privacy law at the American University Washington College of Law as an adjunct professor. She started her career in cybersecurity in 1991 as an analyst at the National Security Agency.