Ireland with egg on its face

Loading...

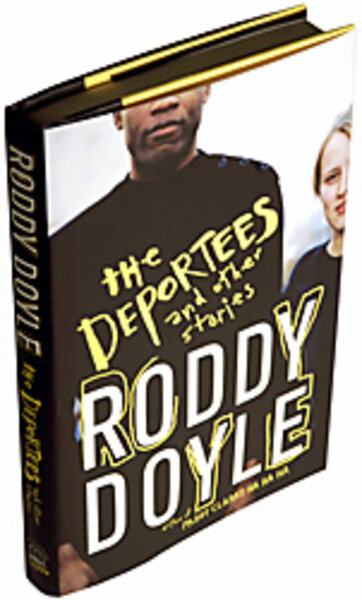

Roddy Doyle has the literary equivalent of perfect pitch, an uncanny ear for the nuances that capture individual character and voice. His deep understanding of the human condition as a juggling act between hope and despair enables him to find the uplifting – and the humor – even in narratives about alcoholism and domestic violence. He has demonstrated his particular attunement to the working class in eight novels, including "The Commitments" and his 1993 Man Booker Prize-winner, "Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha."

With The Deportees, his first book of stories, Doyle expands his range, focusing on the changing faces of Ireland – literally. "Today, one in every ten people living in Ireland wasn't born here," he writes in the book's forward. "It happened, I think, some time in the mid-90s. I went to bed in one country and woke up in a different time."

Americans, of course, are used to living in a multicultural melting pot, but until relatively recently more people emigrated from Ireland than immigrated to it. Doyle jokes that perhaps it was bootleg videos of "Riverdance" shown in Lagos that lured thousands of Nigerians, but then acknowledges that the magnet wasn't line-dancing but education and economics in what "has become one of the wealthiest countries in Europe." The social landscape has altered since his character Paula Spencer cleaned offices with other Irishwomen in the mid-1990s in "The Woman Who Walked Into Doors," he notes. By the time he wrote "Paula Spencer" 10 years later, "the other cleaners were men from Romania and Nigeria."

In other words, Doyle is not a writer stuck inside his own head; he is out there looking around, paying attention to the changing world and the adjustments people make to accommodate it. In each of these eight stories, "Someone born in Ireland meets someone who has come to live here," Doyle summarizes. The stories were originally serialized in monthly 800-word installments (slightly longer than this review) in Metro Eireann, a multicultural paper started by two Nigerian journalists living in Dublin.

Serialization poses special constraints and demands on writers. Deadlines combined with space limitations result in tales that are generally instantly engaging but not always carefully constructed. Instead of the meticulously planned, subtle little masterpieces turned out by his compatriot, William Trevor, Doyle's stories start with a bang but tend to fizzle. Nevertheless, they're remarkable for their lively, accessible take on serious subjects.

In "Guess Who's Coming for the Dinner," Larry Linnane is forced to re-evaluate his attitudes when his daughter brings home a Nigerian accountant. "He tortured himself for things to say, nice things that would prove he wasn't a bigot," Doyle writes wryly.

In the title story, Jimmy Rabbitte, whom readers may recognize as the manager of the eponymous "best Irish band never recorded" from "The Commitments," decides that life has become a bit flat. He rounds up a veritable United Nations of refugee musicians to create a new, multicultural band influenced by Woody Guthrie, which he dubs The Deportees.

Two of the stronger stories are from the perspective of recent immigrants. "New Boy" movingly describes 9-year-old Joseph's first day of school in Ireland, where he must figure out why the teacher keeps asking God to give her strength when there's "nothing very heavy in the classroom." More important, Joseph, who saw his schoolteacher father shot by bullying soldiers at his village school in Africa, must figure out how to handle the young bullies in his new school.

Even more powerful, "I Understand" gets inside the head of a man who's been in Ireland illegally for just three months, working two menial jobs. He's targeted by thugs who try to intimidate him into smuggling drugs for them. But Tom, like Joseph in "New Boy," saw his father die and is tired of running. He, too, figures out a way to reclaim his life.

"The Pram" is a horror story about a Polish nanny's revenge on her foul-mouthed female boss that evokes Henry James's "The Turn of the Screw." "Home to Harlem" concerns a young Irishman determined to find the key to his mixed identity in the Harlem of his African-American grandfather and its literature.

Whether they're immigrants or native Irish, down-and-out or thriving, Doyle shows respect for his characters. He lends them his ear, captures their voices, and endows them with the first thing the hard world so often strips away: dignity. It's a worthy accomplishment.

[Editor's note: The original version misspelled the writer's name.]

• Heller McAlpin is a freelance writer in New York.