Bringing down America's House of Oil

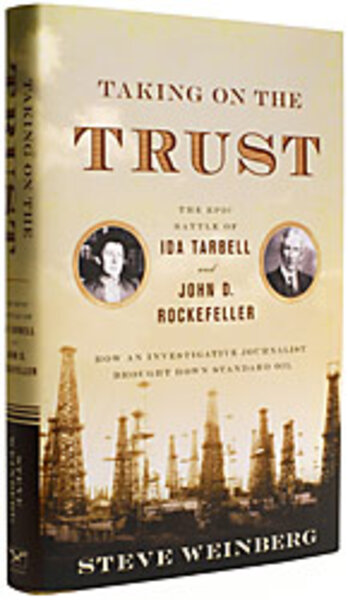

In Taking on the Trust, Steve Weinberg has written a dual biography with a powerful plot: Ida Tarbell, the first investigative journalist, brings down John D. Rockefeller, America's first billionaire and the head of Standard Oil. Weinberg's book tell us how she did it and what it meant for the United States.

Weinberg, who is a journalist himself, clearly sides with Tarbell, the star reporter for McClure's, the trendsetting magazine of the Progressive Era. Tarbell paved the way for women journalists, with bestselling biographies of Abraham Lincoln and Madame Roland. But despite her literary success, she harbored strong grievances against John D. Rockefeller, whose ability to market oil at eight cents a gallon enabled him to sell a phenomenal 60 percent of all oil sold in the world.

Back in Rockefeller's heyday, oil was mainly refined into kerosene to illuminate homes and offices. While most refiners dumped oil by-products into nearby rivers, Rockefeller hired researchers to develop waxes, paving materials, and detergents from the seemingly unmarketable sludge. He also developed the technology that enabled him to extract more kerosene out of a barrel of oil than anyone else. Rockefeller became a billionaire by making a fraction of a cent selling millions of gallons of kerosene to every civilized part of the earth.

New wealth for many

Weinberg admits that the deal was often a win-win for everyone. The US became a major industrial power and inefficient refiners in the US sold out for Standard Oil stock, which often made them comfortable for life. As one editor in oil-rich Titusville, Penn., exclaimed, "Men until now barely able to get a poor living off poor land are made rich beyond their wildest dreaming."

What, then, was the problem? For many Americans, there was none. Ida Tarbell, however, grew up in the Pennsylvania oil fields with a father who chose to compete with Rockefeller rather than sell to him. When Franklin Tarbell proved unable to market oil for eight cents a gallon, he brooded at home and Ida's blissful childhood was damaged. Her brother later became an officer for a competing oil company, adding to the family's grumbling about Standard Oil.

Entrenched at McClure's, Tarbell decided to tell her version of the Rockefeller story. He was a cutthroat competitor, she insisted, who relied on rebates to outsell his rivals. "The ruthlessness and persistency with which he cut and continued to cut their prices drove them to despair," she wrote. Furthermore, he low-balled those whom he sought to buy out. Innuendo became a powerful Tarbell tool: "There came to be a popular conviction that the 'Standard would do anything.' " Even his house was ugly, Tarbell complained.

Taking on monopolies

Her "History of the Standard Oil Company," when published in 1904, came right after a wave of mergers – U.S. Steel, for example, was a billion-dollar company that controlled about 60 percent of the steel market. Were monopolies – with higher prices that would come later – the future for American industry? Competitors of Rockefeller and U.S. Steel were quick to say yes and to ask for a strict interpretation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Presidents Roosevelt and Taft agreed, and they helped set the precedent that allowed the government to break large companies into smaller pieces.

As for Rockefeller, Weinberg observes that he chose to ignore Tarbell's attacks. A high-quality product and millions of customers, Rockefeller argued, were the proper antidote to Tarbell's charges. However, that passive strategy failed, and Standard Oil was broken up into more than 30 separate companies by the Justice Department in 1911. Weinberg wryly notes that these companies often went on to even greater prosperity, but, nonetheless, the idea prevailed that "restraint of trade" needed to be interpreted narrowly in order to break up behemoth corporations such as Standard Oil.

Weinberg seems pleased with that result, and the Wal-Marts of today should take note: Political agitation plus muckraking can defeat a competitive product.

The depth of research on display in "Taking On the Trust" is impressive, but Weinberg is too quick to take Tarbell's allegations as facts. She exaggerated the dangers of Standard Oil, which saved both whales and rivers by finding uses for Pennsylvania's black gold.

Today, as we pay hostile Middle Easterners for more than half of our oil supply, we should perhaps look longingly, not antagonistically, toward John D. Rockefeller, the man whose US company in its prime sold more than half of the oil used in the world.

• Burton W. Folsom, Jr. is professor of history at Hillsdale College and author of forthcoming "New Deal or Raw Deal."