"Nothing Daunted" – a Q&A with Dorothy Wickenden

Loading...

One day Dorothy Wickenden came across a stack of forgotten family letters penned by her grandmother Dorothy Woodruff in 1916-17. That year Woodruff, a restless debutante from a wealthy Auburn, N.Y., family, convinced her best friend, Rosamond Underwood, to move with her to Elkhead, Colo., so they could become rural schoolteachers. (Both young women were Smith College graduates but neither had really ever expected to work. “No young lady in our town,” Woodruff would later recall, “had ever been hired by anybody.”)

Dorothy and Ros stayed for a year, which Ros would later recall as the best of their lives. They boarded with a family of homesteaders and taught in a stone schoolhouse from which they daily watched “cowpunchers ... tearing around the schoolhouse and down the hill at breakneck speed.” They rode to work on horseback, cohabited with wild animals and desperados, and learned to cope with blizzards and students – mostly kids from hardscrabble homesteading families – who sometimes could only reach school by skiing there on barrel staves.

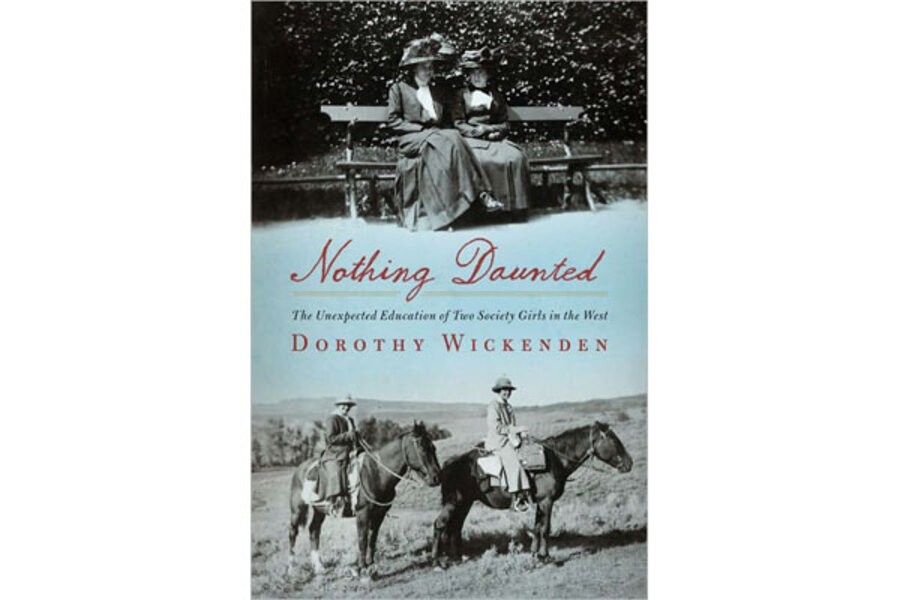

Wickenden, who is also the executive editor for The New Yorker, has written about her grandmother’s real-life adventures in Nothing Daunted: The Unexpected Education of Two Society Girls in the West. She recently spoke with me about her book.

Teaching in a rural school was such a wild and unexpected adventure for two society girls like your grandmother and her friend. Why did they accept these jobs – and how did they adapt to them?

The president of Smith College often asked students, “Are you a leaner or a lifter?” Dorothy and Ros did not want to be leaners, and the opportunities for women in the East seemed far too limited. Once they got to Elkhead, if they were taken aback by the living conditions, they were too proud to admit that to their parents. And their admiration for the stoicism of the settlers helped them shake off any complaints.

What was most unexpected to you about what happened to Dorothy and Ros out west?

What really surprised me was how quickly these two cosseted girls adapted. From the moment they stepped off the train in the tiny town of Hayden in the Rockies, they greeted every challenge either with exclamations of pleasure or with earnest determination.

The America of 1916, as seen through the lens of “Nothing Daunted,” seems at the same time both more innocent and more dangerous than life today. How would you characterize it?

During their time in Colorado, [Dorothy and Ros’s] close friend Bob Perry was kidnapped by two Greek miners – a story so shocking it was front-page news across the country. But the kidnappers, while holding him at gunpoint, were deferential and solicitous about his comfort. As Dorothy grew older, she saw the Holocaust and other horrors of the 20th century, but even late in life she retained her belief that her grandchildren were part of a world that was heading roughly in the right direction. Today I’m not so confident.

One of the more touching aspects of this book is the story of the friendship between Dorothy and Ros. What do you think drew these two girls/women so closely together?

Dorothy spotted Ros across the room on their first day of kindergarten and instantly “fell in love with her,” as she put it. They were well matched: Ros was soft-spoken, generous, gracious, and beautiful. Dorothy was headstrong, funny, and opinionated. Ferry Carpenter, [the book’s] male protagonist, later described Dorothy as the “spark plug” of the pair. Neither would have gone west alone, but together they were, as Ros put it the night before they headed over the Continental Divide, “nothing daunted.” They were friends for 83 years.

Does the America that Dorothy and Ros experienced during their year out west still exist – or has it disappeared?

Much of it has vanished. The homesteading experience didn’t turn out the way people hoped it would, and the railroad they took from Denver over the Rockies went bankrupt long ago. The sense of buoyant optimism that was shared by most of the people in “Nothing Daunted” never really returned after World War I. But during my trips to Colorado, I’ve seen much of what appealed to them – the rugged beauty of the terrain and the self-reliance and warm hospitality of the people there.

Before you wrote this book, did you know much about this story and do you think it affected your life in any fashion?

My grandmother was a wonderful storyteller, so I had heard quite a bit about her life as a child and as a young woman, but her accounts were fragmented. I was only able to put it together into a narrative when I began to track down the letters, photographs, oral histories, and descendants of the people she had described. I also knew little about the history of Auburn or about the building of northwestern Colorado, where much of the story takes place.

All of this reminded me how brief this country’s history is. I was incredibly fortunate that Dorothy and Ros were such dedicated correspondents, and that their families saved their letters. It was the letters that allowed me to reenact their experiences and bring back to life many otherwise forgotten characters.

What’s the most precious thing that you discovered about your grandmother from doing this?

Her sense of humor, which allowed her to take life in stride.

What did you learn about America and the 20th century from doing this?

I was drawn to the animating idealism of the early 20th century. In young Colorado, Dorothy and Ros discovered a triumph of will and perseverance over prudence. They didn’t see much of the darker side of Manifest Destiny, so I explored some of that, too – from Auburn to Elkhead. The big stone school where they taught – built by a few dozen families for their children on the top of a mountain – can be seen as a folly or a monument to hope. The reader can decide which it was.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor's books editor.