As those of us who are kickball-challenged know, there is nothing that can make you feel small and helpless faster than not being picked for a team.

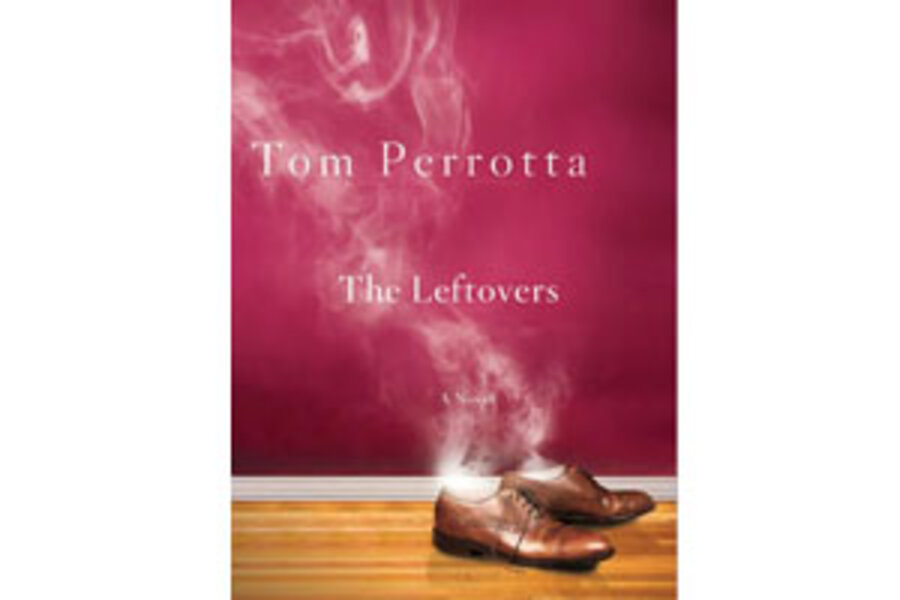

But the feeling of rejection is infinitely worse when the one not picking you is the Almighty, as is the case in Tom Perrotta's The Leftovers.

Set three years after millions of people disappear in a “Rapture-like event,”as the experts termed it, “The Leftovers” follows the Garveys, a family of four who are among the dazed and disillusioned left behind. Society is torn between grieving for those who are gone and trying to figure out what it's supposed to do now. The four horsemen never showed, and neither did Michael or his angels, but it's sort of hard to worry about grades or work or even global warming. “[T]hese days no one bothered much about the hole in the ozone layer or the pathos of a world without polar bears.”

Not everyone is convinced that it was the Rapture, including a number of Christians, who are baffled because the roster of the Chosen did not exactly follow the evangelical playbook. “[M]any of the people who'd disappeared on October 14th – Hindus and Buddhists and Muslims and Jews and atheists and animists and homosexuals and Eskimos and Mormons and Zoroastrians, whatever the heck they were – hadn't accepted Jesus Christ as their personal savior.” On a more personal level, at least one minister can't understand why, after dedicating his life to God, he didn't make the cut. “It didn't matter that God hadn't factored religion into his decision-making – if anything, that made it worse, more of a personal rejection.”

Aside from the supernatural event that launches his novel, the author of “Little Children” is back in familiar suburban territory, surrounded by self-destruction, hypocrisy, and moral ambiguity. Mapleton mayor and Decent Guy Kevin Garvey is determined to make the best of things, end times or not. His wife, Laurie, a former agnostic who “hadn't been raised to believe in much of anything, except the foolishness of belief,” has joined the most ominous of the cults that have sprung up. Members of The Guilty Remnant walk around in pairs dressed all in white, silent and chain-smoking, to serve as “as living reminders of God's awesome power.” Their son, Tom, dropped out of college to follow Holy Wayne, who is now being investigated by the FBI on sexual abuse charges. Tom, in the novel's least-successful storyline, is supposed to take one of Wayne's “spiritual wives” to friends in Boston. Meanwhile, high-school daughter Jill, who was with her best friend when she vanished on Oct. 14, rebuffs her dad's efforts to remain a family, however fractured.

“The Leftovers” isn't as funny as Perrotta's early work, but it's absorbing, intelligent, and has nothing but its central event in common with the “beam-me-up theology” of the Left Behind series. It is unlikely that Harold Camping will make time to read it before next month, when the world is supposed to end again. But the rest of us really should: Perrotta has written a Rapture novel for people who can't stand Rapture novels.