Louise Erdrich, Minnesota, and me

I’ve met Louise Erdrich three times in my life. For some mysterious reason, the acclaimed author always seems to appear at exactly the moment where everything is going belly-up in my life: A potential move abroad. A breakup. A global pandemic.

The first time was amid a quarter-life crisis about whether to move overseas. On a dull day waitressing at the Good Earth restaurant in Minnesota, I happened to see her name on the credit card slip.

“Are you Louise Erdrich, as in, the writer?” I sputtered. She nodded graciously as I blathered on about my love for her books.

Why We Wrote This

Our writer savors three serendipitous encounters with Pulitzer Prize-winning author Louise Erdrich, and shares how Ms. Erdrich’s latest book “The Sentence” brought her home again.

It was ironic, then, that I went to see her at a Paris book fair nearly a decade later – after my subsequent move abroad and a harsh breakup – in search of a sense of home.

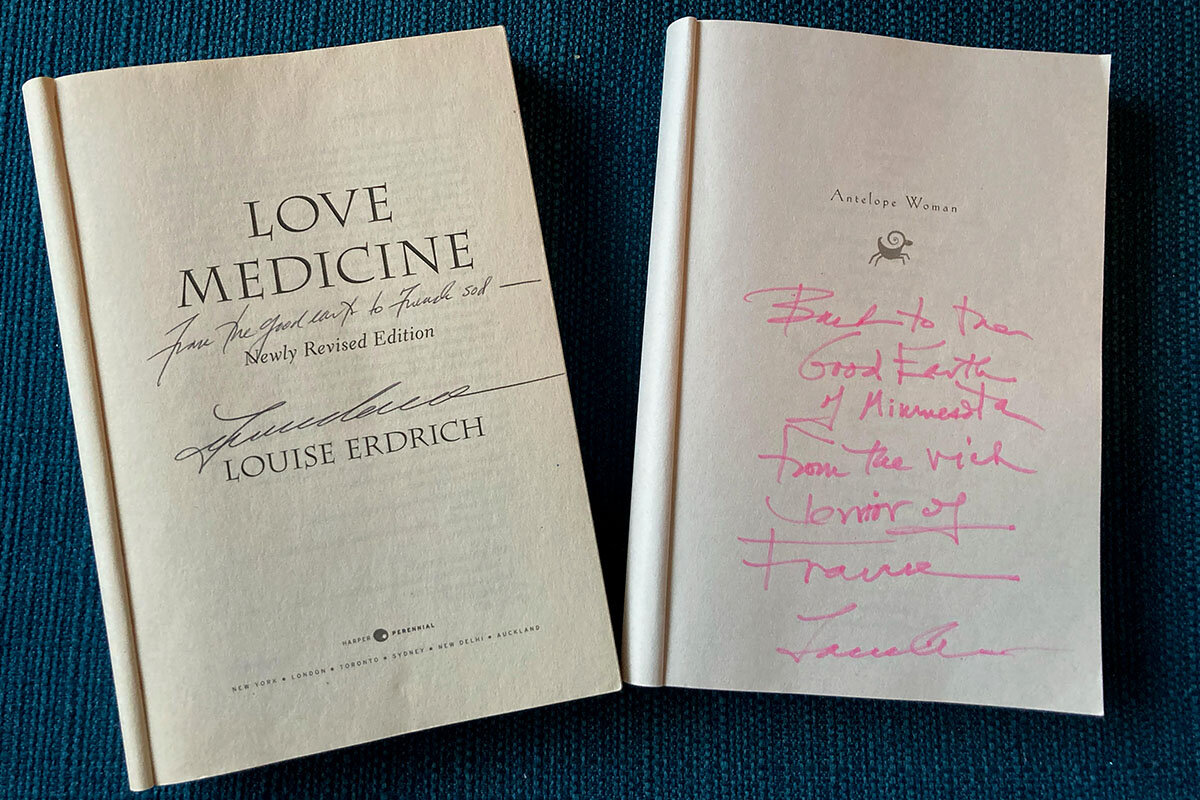

“From the good earth to French soil,” she wrote inside the cover of my copy of “Love Medicine.”

Now, 20 years after that first meeting, Ms. Erdrich has published “The Sentence,” a fictional ghost story that takes place in her real-life bookstore in Minneapolis, Birchbark Books. In it, she tackles George Floyd’s murder and its violent aftermath, Indigenous peoples’ rights, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

For people like me, who’ve been stuck thousands of miles away and unable to properly grasp my hometown’s pain, upheaval, and growth, Ms. Erdrich creates a rare portal into life in Minneapolis over the past 18 months. The main characters in “The Sentence” air common grievances, push readers to reflect on their own biases, and provide an intimate look at the city’s reckoning and rebirth.

“Everything seemed to be cracking: windows, windshields, hearts, lungs, skulls,” she writes. “We may be a striver city of blue progressives in a sea of red, but we are also a city of historically sequestered neighborhoods and old hatreds that die hard or leave a residue that is invisible to the well and wealthy, but chokingly present to the ill and the exploited.”

I couldn’t have known it then, but as I embarked on my first trip home in two years this summer, my life and Ms. Erdrich’s work would overlap once again. Not just in our third and most fortuitous encounter yet, but in parallel discoveries of our city – a Minneapolis split apart, exposed, and sewn together again.

Seeking a connection

I watched the video of George Floyd’s murder last year along with the rest of the world. But as a Minnesotan far from home, I felt helpless, detached, and yet seeking more connection to home than ever.

Mr. Floyd was killed just blocks from my brother’s apartment. My friends worked across from buildings that were torched during the violence that followed his death. I became obsessed with the trial of now-convicted police officer Derek Chauvin, streaming it from my Spanish in-laws’ apartment in June.

Now, at last, there I was in George Floyd Square in Minneapolis amid teddy bears, flowers, and artwork, to remember the man whose tragic death became a wake-up call for my hometown. His killing squashed misconceptions of a harmonious, discrimination-free, “Minnesota nice,” and gave way to the realities of redlining, racial covenants, and over-policing of minority communities.

“It gives me hope that people are listening and doing things, talking about diversity, inclusiveness, and sharing their experiences,” says Angela Harrelson, Mr. Floyd’s aunt. She was in George Floyd Square almost every day, chatting with visitors about whatever was on their minds. “People don’t want to live in fear anymore.”

Ms. Harrelson recognizes the confluence of her nephew’s murder with other acts of injustice in America – Native American land rights, climate change, social injustice, the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on ethnic and racial minority populations.

It’s exactly these themes, and the emotions they unleash, that “The Sentence” works to address. Through Ms. Erdrich’s main characters, readers experience the frustrations of racial inequality and the precariousness of life during a pandemic. Her bookstore clients – desperately and awkwardly searching for connection with the Indigenous community – feel too real to be fiction. She even places herself as the owner, also named Louise, of the bookstore where her story takes place.

“’There is something in me that aches to do the wrong thing,’ said Louise. ... ‘I almost always resist, but I understand when other people don’t. The urge is very strong,’” she writes.

With such true-to-scale depictions, “The Sentence” fulfills a longing in people like me to not just hold my hometown in love and light, but to understand its deep-seated challenges.

The third meeting

On the most recent visit to Minneapolis, I wanted to show my husband and daughters Birchbark Books, never expecting to see Ms. Erdrich there. But when a figure breezed through the front door and began signing books in the back room, I couldn’t believe it. My husband asked me if I was going to say hello.

“Only if it’s natural,” I said, silently hovering by the cash register until she made her way over.

“Hi there, thanks for coming in,” she said, when our gazes finally met.

I introduced myself, referencing our two past encounters. She flattered me, saying she remembered, even though we were both wearing medical-grade face masks. Then I asked what her favorite book was of those she had written. From a sky-high stack she was holding, Ms. Erdrich pulled out a light blue paperback.

“It’s kind of a secret book,” she said.

It was “Antelope Woman,” a newly edited version of “The Antelope Wife,” the first book she published after her husband, writer Michael Dorris, took his own life in 1997. She signed it, referencing our very first Good Earth meeting a million lifetimes ago, and offered it to me as a gift.

Now, as I sit in my Paris apartment, my two signed copies on the bookshelf and Ms. Erdrich’s most recent book on my nightstand, I wonder what effect writing “The Sentence” has had on the author herself. Did it help her process the last 18 months of her life? Has it brought her peace?

“When everything big is out of control, you start taking charge of small things,” she writes in “The Sentence.”

I can only speak to my own experience. Just like those first days in Minneapolis this summer, when I couldn’t focus my thoughts until I had visited George Floyd Square and wrestled with the demons that my city faced, reading “The Sentence” has allowed me to properly grieve.

It has shown me not just what I missed from home but what I was missing – the good, the bad, and the ugly. It’s a rare gift she’s given me – to all of us.

If, by some miracle, I should happen to meet Ms. Erdrich for a fourth time, I’ll be sure to thank her.