The Socrates of second grade: Adventures in philosophy with children

Loading...

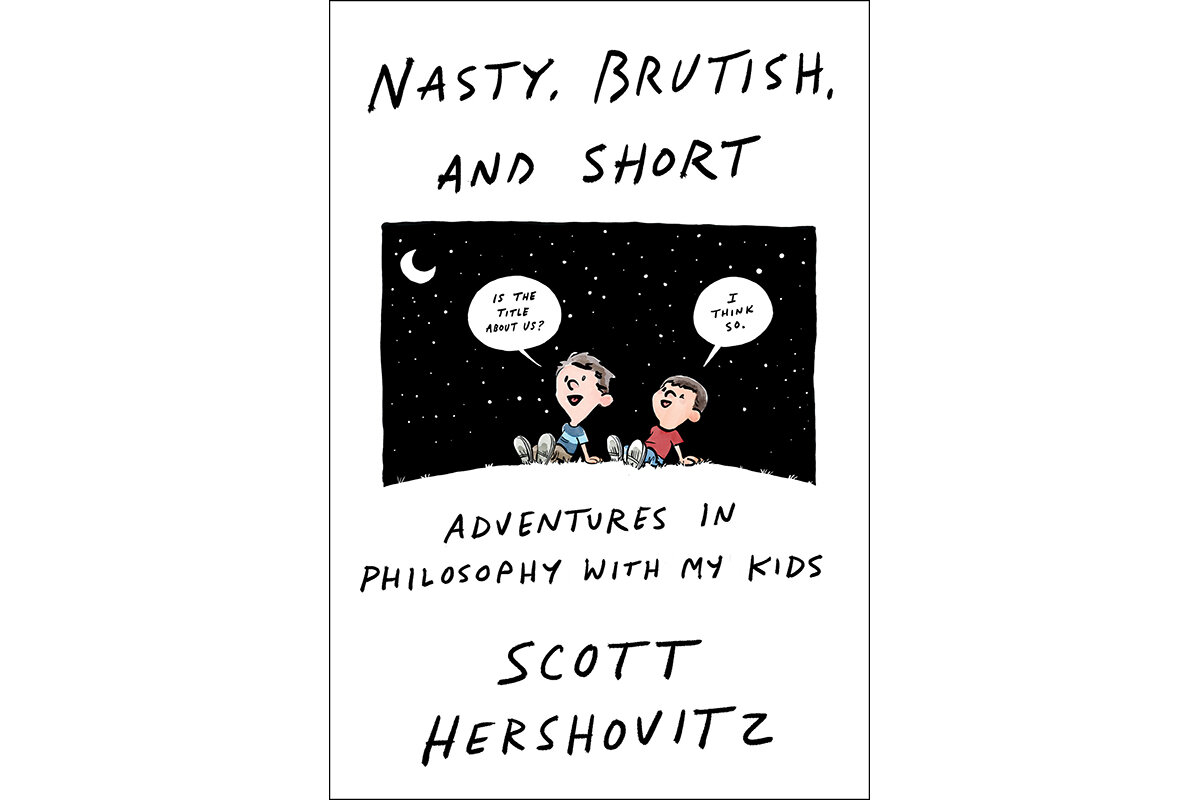

If you’re the parent of a young child, Scott Hershovitz says you’re raising a philosopher “whether you know it or not.” In the delightful “Nasty, Brutish, and Short: Adventures in Philosophy With My Kids,” Hershovitz, a law and philosophy professor at the University of Michigan, uses thoughtful and amusing conversations with his sons, Rex and Hank, to prove his point. He insists, though, that all children harness their creativity and curiosity to make sense of the world, not just those with their own in-house philosopher.

“Nasty, Brutish, and Short” is a bit reminiscent of the NBC show “The Good Place.” The philosophy professor on the sitcom endeavors to teach morality and ethics to an unapologetically amoral person, and his bite-size lessons are woven into the show’s action and humor. Here, the action and humor – of raising children, in this case – offer Hershovitz opportunities to expound upon an assortment of philosophical principles related to rights, punishment, knowledge, infinity, and more.

The book, like the show, is funny (its title uses Thomas Hobbes’ 17th-century description of what life would be like in a state of nature as a tongue-in-cheek characterization of the author’s kids). Not only because kids indeed say the darnedest things – his do from the very first page, when 2-year-old Hank, in need of a tooth flosser, repeatedly insists that he needs “a philosopher” – but also because Hershovitz, raising the boys with his social worker wife, Julie, has a witty and winningly self-deprecating style. In that instance, he is thrilled and then quickly crushed as Hank’s true meaning becomes apparent. “A philosopher is not something that people need,” Hershovitz ruefully observes. “People like to point that out to philosophers.”

Why We Wrote This

What can you learn from children? Many thoughtful and amusing things, if you listen closely and ask respectful questions. From the silly to the profound, the resulting conversations cement family bonds.

Some chapters are responses to a position those familiar with young children will recognize, of a rational being attempting to reason with an irrational one. When Rex refuses to put on his shoes, deploying “you’re not the boss of me,” a phrase he’d recently picked up in preschool, Hershovitz follows with an examination of that claim, exploring the philosophical differences between power and authority. But like many parents, he eventually shuts down the endless back-and-forth with “because I said so,” a phrase he thoroughly parses.

More often, the author is recounting philosophical conversations with his sons. Some are initiated by Hershovitz, as when he asks Hank, in reference to the family dog, “What’s it like to be Bailey?” Others begin with a thought or observation from one of the boys, as when Rex, at age 4, says, “I wonder if I’m dreaming my entire life.” In all cases, Hershovitz takes his sons’ ideas seriously, letting them do most of the talking. “I never pull rank on my kids,” he says. “I won’t tell them what to think about a question, even if I tell them what I think about it. I’d rather they work their ways toward views of their own.”

The book also wades into current cultural debates over transgender women and sports, climate change, and reparations for slavery and segregation. In the latter case, Hershovitz cites philosophers who study race but also applies an example from parenting. “Suppose your kid plays at another kid’s house and breaks something,” he suggests. “You might think that you should take responsibility, even though you weren’t responsible.”

While the author clearly gets a lot of joy out of parenting, he’s no doubt aware that the experience will change. Hershovitz points out that these forays into philosophy work best with young children, who approach the world with wonder and aren’t yet self-conscious enough to worry about embarrassing themselves. His open-ended questions, which yield such fertile results in the book, might soon be met instead with eye-rolling. And when his boys are teenagers testing their independence, he will likely see his parenting recommendation “ask them questions and question their answers” take on an entirely different meaning. By then, though, the bond evident in their mutually respectful dialogues should serve them all well.