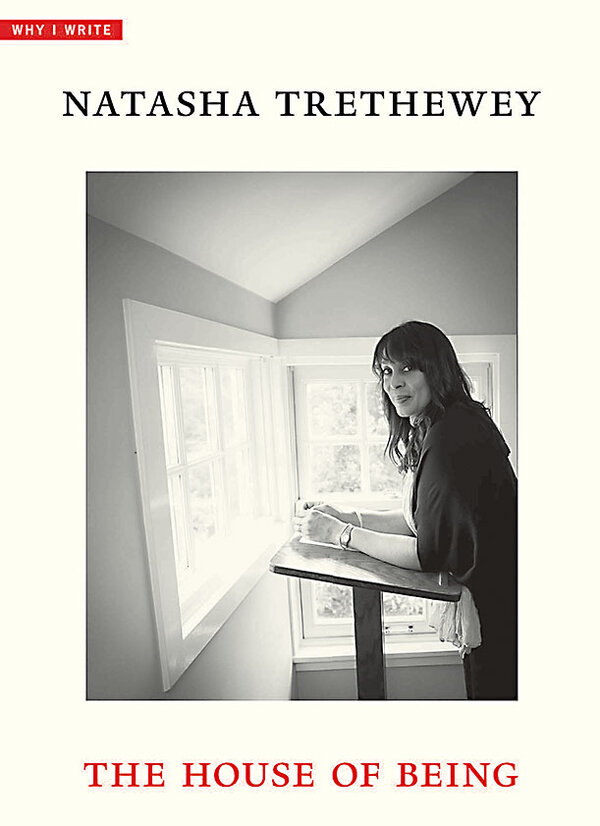

Poet Natasha Trethewey delves into memory in ‘The House of Being’

Loading...

When Natasha Trethewey was born in 1966, her maternal grandmother purchased a set of World Book encyclopedias. The gift spoke of a grandmother’s love, and the books later provided a respite from the world outside.

As the child of a Black mother and a white father growing up in the American South, Ms. Trethewey and her family faced bigotry and hatred. But the encyclopedias, along with her grandmother’s fabric murals, sparked the future poet’s imagination, as she describes in “The House of Being.” The book is part of the “Why I Write” series from Yale University Press.

Why We Wrote This

April is National Poetry Month in the United States. Our poetry reviewer talks with Natasha Trethewey, former U.S. poet laureate, about her new book, “The House of Being,” and about the memories that propel her writing.

In a recent interview, the 2012-2014 U.S. poet laureate discussed how her childhood memories, which include her father teaching her the importance of language, have shaped her desire to write.

“I think he was trying to teach me that all of language influences how we see,” she says. “Language can be used to contain and define us. That understanding was such a gift and so necessary for someone like me, growing up in the Deep South.”

Natasha Trethewey, who served as poet laureate of the United States from 2012 to 2014, deepens her exploration of the memories and landscapes that have shaped her writing in “The House of Being.” The book is a slim yet stunning collection of essays published as part of the Yale University “Why I Write” series.

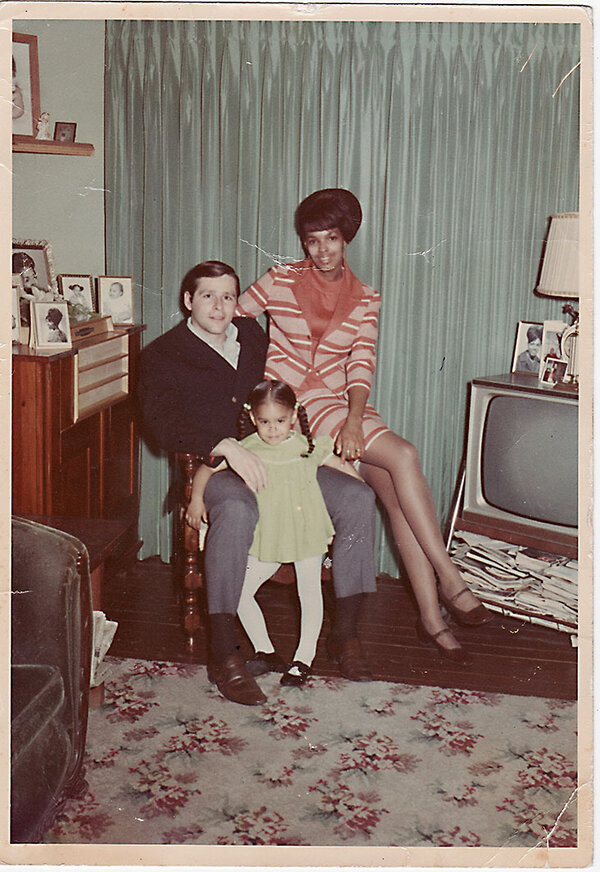

Fans will recognize the broad thematic strokes in “The House of Being,” as illustrated by her parents’ interracial marriage, which was illegal in Mississippi in the year of Ms. Trethewey’s birth. Her mother, Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough, a Black woman, and her father, Eric, a white poet who had emigrated from Canada, met when they were in college in Kentucky. They married in Ohio and returned to the South. Natasha was born in Gulfport, Mississippi. Her grandmother, a seamstress, cared for young Tasha while Gwendolyn and Eric were at work.

Natasha was 6 years old when her parents divorced. Her mother later married a Vietnam vet who was deeply troubled and abusive. For 10 years, he was physically violent with Gwendolyn and emotionally tormented Natasha. After they divorced, he continued to stalk Gwendolyn. When Natasha was 19, he shot and killed her mother.

Why We Wrote This

April is National Poetry Month in the United States. Our poetry reviewer talks with Natasha Trethewey, former U.S. poet laureate, about her new book, “The House of Being,” and about the memories that propel her writing.

“The House of Being” addresses those and other defining experiences, as well as the racial inequities in the South, through the lens of memory and metaphor. The book opens with vivid details about the baby gift Natasha’s grandmother purchased for her: a 20-volume set of World Book encyclopedias. Those books, like the fabric murals her grandmother created, sparked a sense of wonder. They also reminded the future poet of the stark differences between the love and acceptance she experienced within the walls of her grandmother’s house and the bigotry outside them.

Ms. Trethewey has addressed some of those issues in “Native Guard,” a collection of poems, which won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize, and in her memoir “Memorial Drive,” published in 2020.

In a recent interview by video call, the poet discussed how her childhood memories, which include her father teaching her the importance of metaphorical language, have shaped “The House of Being” and her desire to write.

“I think he was trying to teach me that all of language influences how we see,” she says. “Language can be used to contain and define us. That understanding was such a gift and so necessary for someone like me, growing up in the Deep South.”

The importance of metaphor runs throughout the book, as does the impulse to transform one’s surroundings into something more beautiful. Ms. Trethewey learned the latter from her grandmother, who used fabric and oil paint to create window-sized nature scenes of owls and mountains.

“I think everyone has that desire to make something beautiful and to surround yourself with it,” Ms. Trethewey remarks. “People try to curate their worlds and their lives.”

Those fabric pictures decorated a long, windowless hallway and reminded the family of the pasture that once existed behind the house. The art was also a subtle reminder that Black people in Mississippi could only dream of many freedoms. That fact became frighteningly real the night the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross in front of her grandmother’s house, perhaps because they thought it was part of the church across the street, which was holding a voter registration drive, or because of the interracial family inside. “We never knew which,” Ms. Trethewey says.

More lasting markers were visible throughout the South, most noticeably Stone Mountain – a Confederate Mount Rushmore – which could be seen from the front gate of the apartment where Ms. Trethewey’s mother lived and died.

The metaphor of monuments is relevant, she says, because “we’re living in a moment in which the contests over what is remembered, contests over statues and memorialization, and what they inscribe onto the physical landscape and into the landscape of our cultural imagination, are more fraught than ever.”

“I think some people thought of monuments as things that ... no one paid attention to, that they weren’t somehow still speaking to us, some of us at least, about what our place in the culture at large was supposed to be,” she explains. “In the aftermath of the death of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests that were centered around a lot of these monuments, people began to rethink what their place is now, which is why some of them are being removed and put in their proper places.”

In “The House of Being,” Ms. Trethewey revisits themes, including the idea of constellations – both stars and circumstances.

“When you look at the night sky, so many of the stars are, to our view, brighter than others, and there are countless tiny ones that are perhaps harder to see,” she says. “I think of that as a metaphor for how we tell stories about our lives. Which of the stars do you pick out, and how do you draw lines between them to make connections? When I wrote ‘Memorial Drive,’ and when I wrote ‘The House of Being,’ there were countless other details I could have chosen to tell, but you choose the ones that are creating the constellation of story that ... is the one that you can exist inside of, and thrive within.”