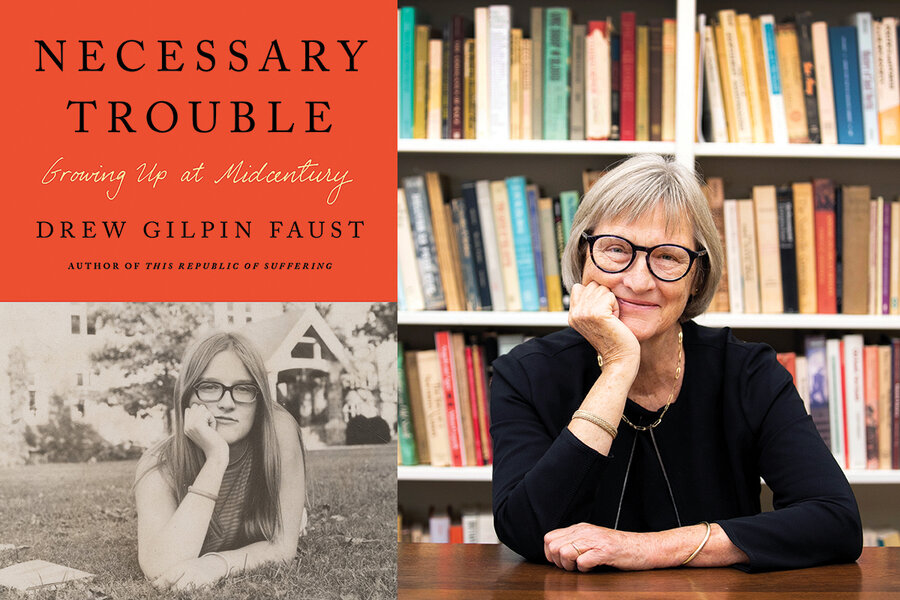

Making ‘Necessary Trouble’: A historian rises above her roots

Drew Gilpin Faust’s memoir is both a moving personal narrative and an enlightening account of the transformative political and social forces that impacted her as she came of age in the 1950s and ’60s. It’s an apt combination from an acclaimed historian who’s also a powerful storyteller.

“Necessary Trouble: Growing Up at Midcentury” describes Dr. Faust’s upbringing as a privileged white girl in segregated Virginia, where she chafed at constraints placed on her because of her gender and was outraged by the racial discrimination she saw around her. (The book opens with a copy of her handwritten letter to President Dwight Eisenhower, penned at age 9, asking him to end school segregation.)

By the time “Necessary Trouble” concludes in 1968, with Dr. Faust’s graduation from Bryn Mawr College, she had rejected the culture in which she was raised, embracing the civil rights and anti-war movements and daring to imagine a different future for herself. She went on to become a scholar of the American South and, later, the first woman president of Harvard University, a position she held from 2007 to 2018. She recently spoke with the Monitor.

What led you to write this book now?

As a historian, I’ve spent so much time listening to voices of the past, be they the voices of bereaved people in the Civil War [in 2009’s “This Republic of Suffering”] or others in the South. I decided it was time for me to be a voice instead of a recorder of voices.

How did you go about balancing the personal and the political?

I was influenced by my work to think that I could explain my life better by situating it within the context of its times and seeing how my choices as an individual had been structured by the events and social expectations that surrounded me. Even as a child I was very concerned about the world beyond my little Virginia farm.

How did the social expectations you describe set you up for conflict with your family?

I hope I paint a sympathetic picture of both my mother and my grandmother. I wanted to show how limited their choices were. They both ended up as unhappy people even though one could say that everything was available to them. They came from very privileged backgrounds, and yet the limits on their ability to pursue meaningful work and make meaningful choices in their lives were enormous. In my lifetime, things were beginning to change in ways that enabled me to find paths that they had not been able to.

As a young girl, you rejected notions of racial hierarchy. How do you account for your keen sense of justice?

I think my awareness of race grew out of my own resentment about the limitations on me for being a girl. I had three brothers, and they could do certain things while I had to do other things. The expectations of us were very sharply different. I was suffused with a sense of “this isn’t fair.” But when I looked around me, I saw social structures that were even more unfair in the ways that Black people were treated in segregated Virginia in the 1950s.

How did books help you see beyond the limitations placed on you?

Nancy Drew and Anne Frank and “To Kill a Mockingbird” and other books showed tough young women who were forging their own paths. They empowered me in ways that continued to influence me into high school and college.

You write that from an early age you recognized “the force and the burden of history.” Can you say more about that elegant phrase?

I grew up in the Shenandoah Valley in the years leading up to the Civil War centennial, so the war was very much around me, and it was very much a hagiographic approach to the "Lost Cause." Understanding that this event that had happened 100 years ago was still something people felt so vividly was part of my learning about the sense of history.

Then I came to understand that what that war had really been about was slavery. [In the aftermath of the Brown v. Board of Education decision, when there had been] a rather genteel approach to race relations on the part of white Virginians, where race was not much talked about, race was suddenly talked about constantly, with a need to resist the mandated integration of schools. I could see links between this Civil War heritage and this [challenge to integration]. So in that sense, history was always present, and its implications were essential elements of my life.

Your title was inspired by U.S. Rep. John Lewis. What did he mean to you?

I had the great privilege of getting to know him during my years as Harvard president. He agreed to speak at my last commencement. Before he started speaking, he turned to me and said, “Thank you, Madam President, for making necessary trouble.” That moved me greatly.

When I was thinking about this book, it seemed to me that that was absolutely the right phrase for my childhood, that in a way I had no choice: If I was not going to be miserably unhappy like my mother and grandmother, if I was going to lead a life that seemed just and fair, I was going to have to make trouble. And so it was necessary trouble for me.