Bohemian rhapsody: Two writers celebrate Greenwich Village of the ’60s

Loading...

Los Angeles had Laurel Canyon. San Francisco had Haight-Ashbury. And New York City had Greenwich Village. Their respective music scenes shaped the 1960s. Greenwich Village came first.

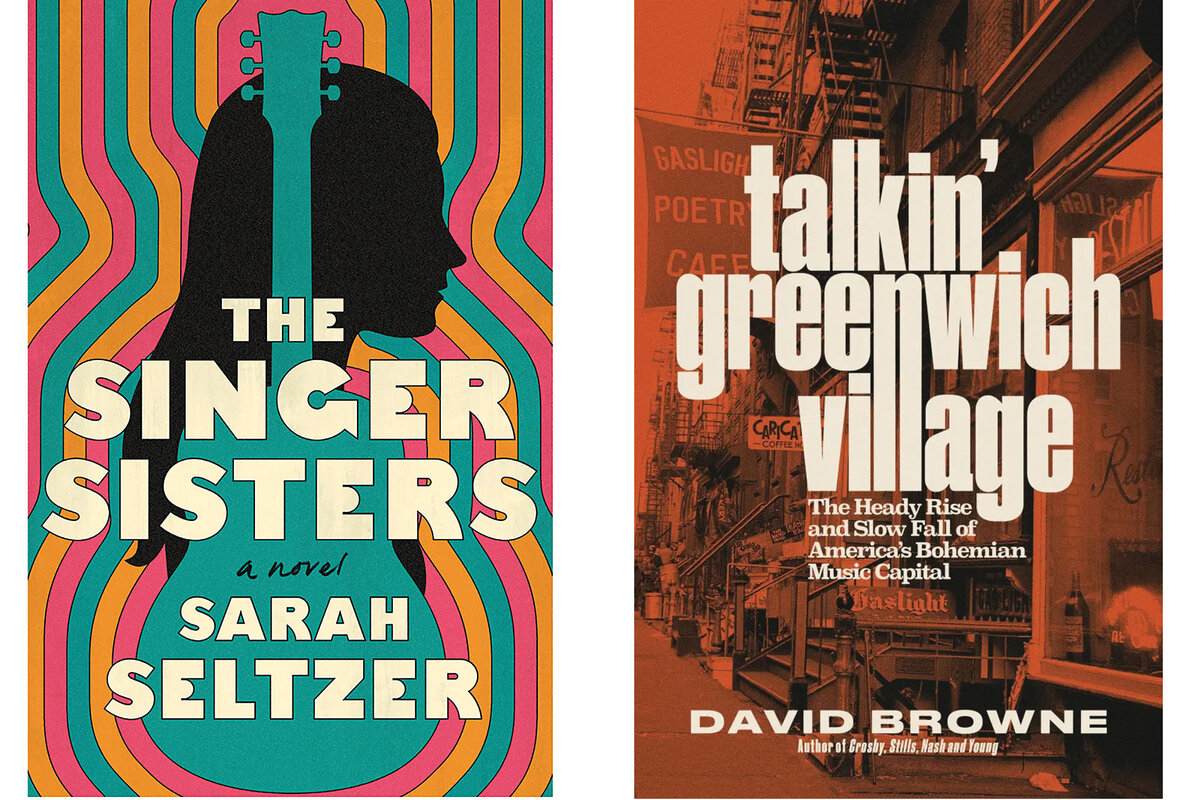

Two new books capture the cultural impact of the lower Manhattan neighborhood that sits almost 30 blocks south of Times Square. Sarah Seltzer’s debut novel, “The Singer Sisters,” is about a songwriter, Judy, who arrives in the Village in 1965. David Browne’s nonfiction “Talkin’ Greenwich Village” is a history of the bohemian locale. Originally a hub for writers and, later, beat poets, its clubs birthed the cool jazz of Miles Davis. It also incubated modern folk music.

It was a neighborhood where the likes of Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and the trio Peter, Paul and Mary could develop their singular musical styles, says Mr. Browne, a journalist at Rolling Stone. That certainly describes Ms. Seltzer’s fictional character, who becomes the matriarch of a folk rock dynasty.

Why We Wrote This

The 1960s music scene in New York’s Greenwich Village shaped American culture. We invited a novelist and a music journalist – both with recent books about the Village – to explore the neighborhood’s vibrant legacy.

The Monitor convened the two New York writers on a video call to discuss Greenwich Village’s legacy. This interview has been condensed and edited.

Can you describe what your books are about?

Ms. Seltzer: It’s a family saga about two generations of folk rock singers in the ’60s and the ’90s. And their secret betrayals and brushes with fame and infamy, and mostly about their relationships and how those are expressed through song.

Mr. Browne: My book is a history of the rise and heyday and gradual crumbling of the legendary Greenwich Village music scene. And how, over those decades, it fostered all kinds of talents and iconoclasts and musical rebels in many genres. And became an iconic ... gathering place.

What was your response to each other’s book?

Ms. Seltzer: I’ve been thinking about how important setting is. And using place as an organizing principle for a nonfiction book is really cool. ... But what’s so interesting about this book is how the locus of what was cool and the public spaces where new music was being fostered were also shifting around, even within the space of a few blocks. And that really resonated with me just as a New Yorker myself. As someone who’s made pilgrimages down to that part of the city my whole life, seeing how it changes and how the cool spot can change from one year to another – that’s really captured so well in this book.

Mr. Browne: It was fascinating to see some of the places that I wrote about, some of those clubs that are mentioned, like the Bottom Line and the Washington Square Hotel, which was a gathering place for musicians, kind of seedy back then. That blend of fiction and nonfiction reminded me of a book like E.L. Doctorow’s “Ragtime,” which I read when I was a kid and just loved. But I also love the alternating stories of two generations of musicians and how they each embodied their eras. [The character of] Judy captures a certain ’60s and ’70s moment in music and the singer-songwriter thing. And [her daughter] Emma captures that ’90s kind of a Lilith Fair vibe, which was very much an inheritor of the previous generation. I joked to Sarah when she told me about the book, “Oh, it’ll be like if Joan Baez gave birth to Jewel.”

Who were some of the real-life musicians who influenced your characters in “The Sister Singers”?

Ms. Seltzer: Some touchstones are obviously the Wainwright-McGarrigle [family] and Roche mega family and all their drama. There’s Joan Baez and her sisters. Carly Simon and her sister [Lucy] were in a band together, The Simon Sisters, and they did folk music at first. Joni Mitchell, obviously, as well. I also read a biography of Janis Joplin while I was researching. I found that really helpful in different ways, like her relationship with her family. While she was rebelling against them in this very serious way, she was also writing these heartfelt letters back and forth to them. That really helped thinking about the emotional tenor of the family relationship [in my novel].

Actor Timothée Chalamet plays Bob Dylan in the upcoming biopic “A Complete Unknown.” It’s set in Greenwich Village during the ’60s. Why does that era still have such a powerful hold on popular culture?

Ms. Seltzer: There’s so much ferment in the ’60s in New York. It’s political; it’s cultural; it’s musical. And it’s a beautiful neighborhood. ... It exerts its call on every generation of artists because they know what happened there. I have a book my parents got me when I was a teenager [about] literary Greenwich Village in the 1920s and ’30s. Edna St. Vincent Millay and Dylan Thomas were hanging out in these same places before the people that David wrote about. I hope the movie’s really good. And I hope that people discover Dylan’s music. It’s for every generation.

Mr. Browne: It’s been fascinating over the last decade or so to see the Village come back a bit more into pop culture, with [the Coen brothers’ movie] “Inside Llewyn Davis,” of course, and [the streaming series] “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.” [Midge Maisel] starts off her career as a comedian in the Gaslight and hanging out with Lenny Bruce. And now leading up to this movie, it really shows the ongoing allure of that neighborhood, not just the music that came out of it, because those songs really endure. Not just Dylan’s [songs], but “Four Strong Winds” by [the folk duo] Ian and Sylvia, and “Reason To Believe” by Tim Hardin, and “Tom’s Diner” by Suzanne Vega.

These days, if you go to the Village, it’s all [marijuana] dispensaries and drugstores and banks. If you’re young and you go down there, the idea that there was all this stuff happening and all these little basements and storefronts and things, I think it’s very romantic. It’s very tantalizing.

Years ago, Taylor Swift briefly rented an apartment in Greenwich Village on Cornelia Street – and wrote a song by that name. What would you tell Swifties about the musical lineage of the neighborhood?

Mr. Browne: I have a friend who lives on Cornelia Street right next to that building. He sees the Swifties. They gather in front of that building and have their photos taken. What made [the area] special was just a combination of things. Within less than a mile, there were a half a dozen or more clubs. You could just pop in from one to the next, and you could see jazz here and folk here and some blues rock there. We think of the Village as [associated with] protest songs, and it really wasn’t. A lot of the songwriters, even back in the ’60s, were writing about what was going on in their minds and relationships.

Ms. Seltzer: I was like, should I have my book [release] party down there? Because it’s kind of touristy now. As my brother was coming to the party, he texted me Counting Crows’ lyrics [for] “Sullivan Street” because he was crossing Sullivan Street. In that radius, there are more songs with the names of streets. So there’s [Taylor Swift’s] “Cornelia Street.” There’s “Bleecker Street” by Simon and Garfunkel. Dar Williams is my favorite folk rock singer from the ’90s and 2000s. She has a song called “Spring Street” that is so good. There’s [Dylan’s] “Positively Fourth Street.”

I can’t think of anywhere else that’s like that, you know? Even with all the waves of decay that David describes so well in his book, and reinvention, it still feels really special.

Which performers do you hope gain greater recognition as a result of “Talkin’ Greenwich Village”?

Mr. Browne: When people think of the Village, they think of Bob Dylan – and they think of some of his peers back then, Phil Ochs or Tom Paxton – but it often doesn’t go beyond that. There were a whole raft of people of color on the scene. Folk singers who have been forgotten. Len Chandler being one of the big ones. He was a peer of Dylan’s and the first folk singer to sing in the Gaslight Cafe. He never quite got his due. I tracked down a woman named Delores Dixon, who was a Black folk singer in the Village, who was in a group called The New World Singers. They did the first cover of “Blowin’ in the Wind” before Peter, Paul and Mary. Most people don’t remember her.

What role did Greenwich Village play in helping the culture accept gay rights?

Mr. Browne: There was a lot of gay entertainment in the Village in these little bars and clubs back in the ’20s and ’30s. All of them got shut down pretty quickly because they were raided. But it continued. There were these tea rooms where gay women would gather. I discovered a place called the Page Three, which was on Seventh Avenue South and had cross-dressing clientele in the ’50s. That was an amazing thing for me to discover and to talk to some of the performers. The Stonewall riot in 1969 in the Village was such a horrific thing, but also an important moment for gay rights. Even the Village People, as silly as that seems, grew out of the West Village. Those [music] producers going to gay bars and seeing all these people dressed in different outfits and thinking, “Oh, there’s this audience. They love this kind of music. Let’s concoct a group and even name it the Village People.” So the Village paralleled the emergence of gay rights.

When you were each doing research, what surprised you?

Ms. Seltzer: Reading in David’s book – and then I also read “Folk City” [by Stephen Petrus and Ronald Cohen] and a couple of others – about the women who were so instrumental in hosting gatherings and bringing male artists to the attention of record labels. There’s always those women in any kind of scene making connections happen, and whose names have been forgotten.

Mr. Browne: When I was interviewing John Sebastian of The Lovin’ Spoonful, he lived in a building on Washington Square West. He was one of the few musicians who actually was from Greenwich Village. And, briefly, his neighbor was Eleanor Roosevelt. There was a movement in the ’50s ... to run a highway through Washington Square Park. One of the people who really publicly advocated against that plan was Eleanor Roosevelt. Woody Guthrie sometimes crashed in John Sebastian’s family’s apartment because John Sebastian’s father was a classical harmonica player. So the idea that in this one building, at one point, you had the future leader of The Lovin’ Spoonful, Woody Guthrie, and Eleanor Roosevelt – that just captured the whole crazy quilt of the Village arts and politics scene.