When death came marching home

“Your son, Corporal Frank H. Irwin, was wounded near Fort Fisher, Virginia, March the 25, 1865.... He died the first of May.... He was so good and well behaved.... I do not know his past life, but I feel as if it must have been good.”

It’s not one of Walt Whitman’s better known pieces of writing but it may have been among his most heartfelt. During the US Civil War, the poet was a tireless visitor to Washington, D.C., hospitals, not only ministering to wounded and dying soldiers but also writing hundreds of letters to their families. Often the only good news he could offer was that their loved one had died honorably and not entirely unnoticed.

Sadly – horrifically – these families were among the fortunate. At least they knew. Thousands of others, on both sides of the war, watched brothers, sons, husbands, and neighbors march off and then waited for news that never came.

Decades later some were still waiting.

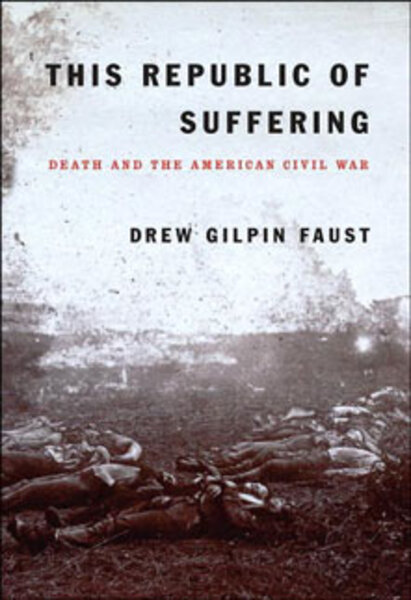

I sometimes thought while reading historian Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War that she should simply have called her book “Misery.” “We all have our dead – we all have our Graves,” intoned a Confederate Episcopal bishop in a 1862 sermon. But even by contemporary standards it’s hard to grasp the carnage of the US Civil War.

An estimated 620,000 soldiers died between 1861 and 1865 – equal to the total American fatalities in the Revolution, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, and the Korean War combined. Add to that at least 50,000 civilian deaths.

“This Republic of Suffering” is a harrowing but fascinating read. Faust (who is the president of Harvard University) makes a convincing case that since the heartbreak of the Civil War the US has never been the same.

On an institutional level, the government was prompted to become a caretaker and custodian of its citizens in a way that it never had before. But more poignantly, Faust argues, the Civil War raised questions about individual worth that we have yet to answer today.

In some ways, the peculiar horror of the Civil War was that it introduced modern warfare to a nation utterly unprepared to understand it. “How does God have the heart to allow it?” cried Confederate soldier and poet Sidney Lanier. Modern weapons deployed on small battlefields meant that “the Civil War placed more inexperienced soldiers, with more firepower and with more individual responsibility for the decision to kill, into more intimate, face-to-face battle settings than perhaps any other war in history.”

At the same time, photography brought the ugly reality of mass killing right into the home. Civilians once able to envision war as glorious had that luxury no more.

But what was perhaps cruellest about the war was its impersonality. The government had no means for tracking, burying, and acknowledging the dead. More than 40 percent of Union – and even more Confederate – fatalities were identified only as “Unknown.”

It wasn’t just that Americans experienced death. It was the way they experienced it – on so dehumanizing a scope and scale. For so many there were not even the traditional consolations – a ceremony, a gravestone, public recognition, a sense of meaning.

It is the struggle for meaning that is at the core of this book. How did mourners face the unbearable? They found ways to bear it.

Some threw themselves into the effort to find, identify, and rebury the remains of soldiers.Bravo Moon of New York traveled to Antietam to dig up his brother-in-law’s body after a colleague described where it had been buried. He bought a coffin, caulked it himself, and bribed a train official to have it shipped back home.

At Gettysburg, that story was repeated over and over again as the bodies of 1,500 Union soldiers were shipped home at private expense. In the South, bereaved women banded together to raise money for Confederate burials.

Finally, the government could no longer ignore such yearnings. National cemeteries, next-of-kin notification, military pensions, and records of the fallen all date from the Civil War. Ambulance service on battlefields began only when heartbroken Boston surgeon Henry Bowditch learned that his son had died unnecessarily on a Virginia battlefield, waiting for help that never came. Bowditch made it his quest to change the system.

But on a deeper level, many Americans wrestled with questions of why it had happened and whether such loss could ever be compensated. The literal word of the Bible wasn’t sufficient consolation for some. Elizabeth Stuart Phelps caused a sensation with her bestselling novel “The Gates Ajar” in which a grieving sister declares, “I am not resigned” to traditional ideas of death and insists on new, more comforting notions of afterlife.

The struggle for meaning took many shapes and forms. For a slave named Aunt Aggie, the sight of so many dead white bodies could only mean one thing: God was finally punishing slavery. For Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., wounded at Antietam, it meant a “collapse” of all the beliefs of his youth, Christianity included.

But what fascinates Faust – and makes for a grim conclusion to her book – is the sense that the conundrum introduced by the Civil War is with us yet. As long as modern warfare permits mass killing, she writes, “we still struggle to understand how to preserve our humanity and ourselves in such a world.”