Thrilling woes of that thing called ‘love story’

Loading...

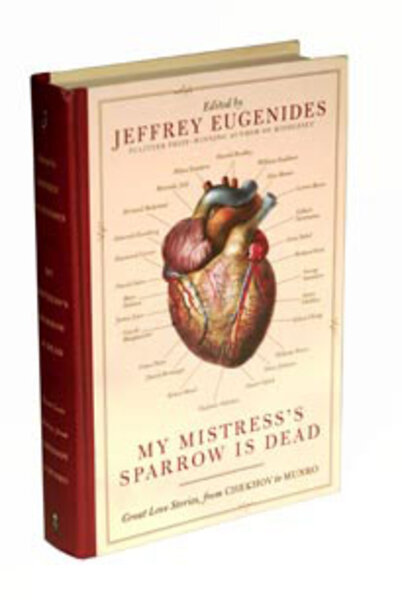

Don’t be put off by the strange title, which Jeffrey Eugenides plucked from the Latin poet Catullus’s verse bemoaning having to share his lover’s attention with her pet sparrow.

It’s the only off note in this otherwise irresistible anthology of 27 love stories sure to make hearts flutter well beyond Valentine’s Day. My Mistress’s Sparrow Is Dead was edited by Eugenides at Dave Eggers’s behest, to benefit the Chicago chapter of 826 National, his writing programs for teens, a cause as worthy as amour.

Eugenides’s point is that love stories – as opposed to love itself – thrive on obstructions: sparrows, dead or alive. As he explains in his introduction, they “depend on disappointment” and “nearly without exception, give love a bad name.” What he doesn’t mention is that reading love stories thrillingly combines the pleasures of prurience and schadenfreude.

Unlike Zadie Smith, who commissioned new stories by hip young writers for “The Book of Other People,” her anthology for Eggers’s literacy project, Eugenides sought suggestions rather than submissions from contemporary authors.

Although some of Eugenides’s featured writers – Harold Brodkey, Mary Robison, Vladimir Nabokov, William Trevor – also appear in Roger Angell’s 1997 anthology of love stories from The New Yorker, “Nothing But You,” there is, remarkably, no duplication of stories. Eugenides’s collection tucks many old favorites together between covers for the first time.

What a treat to reread William Faulkner’s Gothic tale of perverse attachment, “A Rose for Emily.” Or Bernard Malamud’s beguilingly cagey give-and-take between a young rabbi and his matchmaker in “The Magic Barrel.” Anton Chekhov’s “The Lady with a Little Dog,” one of the best stories ever written about how even illicit, initially cavalier, love gets under your skin, is another welcome classic. My only complaint is that the translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, responsible for the acclaimed new translation of Tolstoy’s “War and Peace,” replaces the familiar pampered “Lapdog” of the title with the more literal but less resonant “Little Dog.”

Eugenides also shows unerring taste when cherry-picking from more recent story collections. Deborah Eisenberg’s “Some Other, Better Otto” movingly captures the domestic dynamics between a curmudgeonly lawyer and his “sunny, his patient, his deeply good” longtime better half, William. Alice Munro’s heartrending story about a woman with Alzheimer’s disease, “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” – the basis of the film “Away From Her,” starring Julie Christie – is a nuanced portrait of a marital connection that transcends transgressions.

Equally well chosen are the unfamiliar revelations. In “Red Rose, White Rose,” Eileen Chang spins a subtle morality tale about a Chinese businessman in simple, unaffected prose. After sleeping with a friend’s flirtatious wife, “It was as if he’d fallen from a great height. An object that falls from high above is many times heavier than its original weight.”

Adultery is a perennial fascination. Vladimir Nabokov’s “Spring in Fialta,” an exquisite elegy to a doomed extramarital affair, concerns a woman who, for 15 years, “Again and again ... hurriedly appeared in the margins of my life, without influencing in the least its basic text.”

More ferocious – and funny – is Lorrie Moore’s “How to Be An Other Woman.” This second-person tour de force captures the desperation of being pulled into a hopeless romance. “When you were six you thought mistress meant to put your shoes on the wrong feet,” she writes. “Now you are older and know it can mean many things, but essentially it means to put your shoes on the wrong feet.”

The vulnerability of first love is another object of writers’ affections. It is often filtered through what Nabokov calls “memory, that long-drawn sunset shadow of one’s personal truth.”

David Mezmozgis’s “Natasha” presents a fresh voice set among recent Russian immigrants in Toronto’s suburbs. His horny 16-year-old narrator’s dismaying relationship with the prematurely hardened young daughter of his uncle’s Russian mail-order bride provides “connection to a larger darker world.”

Stuart Dybek’s “We Didn’t,” about a couple who miss their moment, is mesmerizingly beautiful: “But we didn’t, not in the moonlight, or by the phosphorescent lanterns of lightning bugs in your back yard ... because of fate, karma, luck, what does it matter? – we made not doing it a wonder....”

The wonder of “My Mistress’s Sparrow Is Dead” is that it manages to capture a deep as well as broad range of this funny thing called love, without succumbing to the laundry-list effect that afflicts anthologies that try to be all-encompassing: adultery, check; lesbians, check; May-December romance; check. By focusing on literary merit, Eugenides has produced a treasury worth holding dear.