Gandhi and Churchill: parallel lives, divergent world views

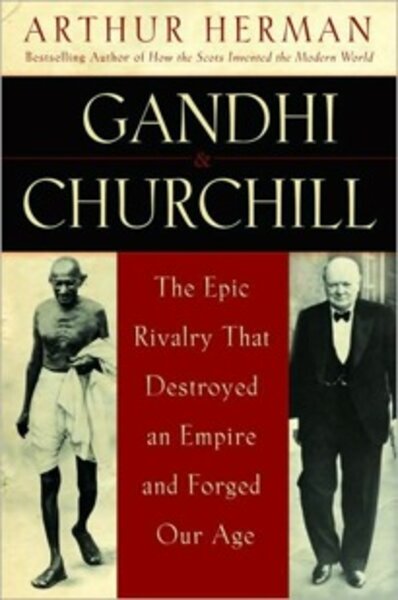

Compare-and-contrast biographies of great leaders which weigh the similarities and differences of each have long proved a popular and informative subgenre. Now, historian Arthur Herman (author of “How the Scots Invented the Modern World”) brings us his version of the parallel biography in Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age.

Mohandas Gandhi was born in rural India in 1869; he studied law at London’s Inner Temple. He subsequently found work in South Africa, serving with the Ambulance Corps during the Boer War, working for Indian rights, founding communes, and writing philosophical treatises on nonviolent civil protest. Returning to India, he founded more communes, became a key member of the Indian National Congress, and a leader in the movement for Indian independence. He was assassinated in 1947.

Winston Churchill was born in England in 1874; he served with the British Army in India; he saw action in what is now the Pakistan/Afghanistan border region, also in the Boer War in South Africa. He was a member of Parliament and served in several cabinet posts including that of chancellor of the exchequer. Throughout the 1930s, he warned of Hitler’s rearmament of Germany. As prime minister during World War II, he was, with Roosevelt, the driving force behind the Allies’ ultimate victory over Nazism, the Axis powers, and Japan. He was also a prolific author and historian, winning the 1953 Nobel Prize for Literature for his five-volume work on World War II.

Yet a side-by-side biography this is not, for it is remarkably short on the facts of either man’s life. Instead, its 704 pages are frequently filled with Herman’s soliloquizing on Gandhi’s political-cum-spiritual theories.

Certainly, this describes the first half. Here, Herman treats us to lengthy discussions of Gandhi’s first encounters with vegetarianism, various theosophists, and spiritualists, as well as Gandhi’s evolving ideas which fused elements of Hindu spiritualism, a rejection of Western modernity and industrialization (with an emphasis on the universal use of the spinning wheel), with his nascent political aims and his ideas for nonviolent civil disobedience. The latter he tried to implement on behalf of his fellow Indians in South Africa, but with limited success. Actually he failed to achieve any of his objectives.

Gandhi returned to India in 1915 and channeled all his energies into the causes of Indian nationalism and independence. Yet his plans for independence were based upon his own utopian dream of Indian history, unrelated to the facts of religious, political, or tribal history. For a brief spell, this dream captivated his fellow countrymen, unifying them.

Initially, Churchill emerges as engaging, energetic, and intellectually vibrant, although Herman understands little of the nuances of British education, class and political divides, or the subtleties of British patriotism as engendered by a public school education, which was central to Churchill’s character.

Churchill, wholly alive to the discrepancies between Gandhi’s beliefs and reality, vigorously opposed Indian independence, seeing it as a blueprint for bloodshed and chaos on an unimagined scale. Churchill is vilified as a hateful, bombastic, belligerent, reactionary racist, prone to pursuing disastrous political and military policies and deranged on Indian matters. Rarely missing an opportunity to quote from a Churchill detractor, Herman lays the blame for whatever went wrong in two World Wars squarely on his shoulders. He views the attempted British evacuations of Malaysia and Burma in 1941-42 as cowardice.

Herman depicts Gandhi as a 20th-century Francis of Assisi, yet as the fight for independence advanced, and especially during World War II, he appears increasingly willful and manipulative. Though constantly stressing the difference between Gandhi’s “spirituality” and Churchill’s faith in the betterment of humanity through civilization, Herman writes of the bloodbath that preceded full independence: “[Gandhi’s] decade and a half of defiance of the law through civil disobedience had bred an atmosphere of contempt for social order, a celebration of recklessness and militancy ... by encouraging others to see themselves in his exalted image, Gandhi helped to spread the dangerous fiction that all street action was soul force and vice versa.”

Finally, in no sense were Churchill and Gandhi rivals, despite Herman’s suggestive title. But their legacies are plain to see. Churchill’s is a stable, prosperous, Europe, while Gandhi’s dream of a primitive utopia has given way to an Indian subcontinent whose quest for international technological status and democratic principles would make Churchill beam from ear to ear.

M.M. Bennetts is a freelance writer in Hampshire, England.