A 'thoroughly modern' Middle East

It’s hard to imagine a less intrepid explorer than Agnes Shanklin, Ohio schoolteacher. The middle-aged spinster (who says she looks like a cross-eyed young Eleanor Roosevelt) has never been outside her home state. And yet, Agnes tells readers of Dreamers of the Day, they’d better pay close attention. “My little story has become your history. You won’t really understand your times until you understand mine.”

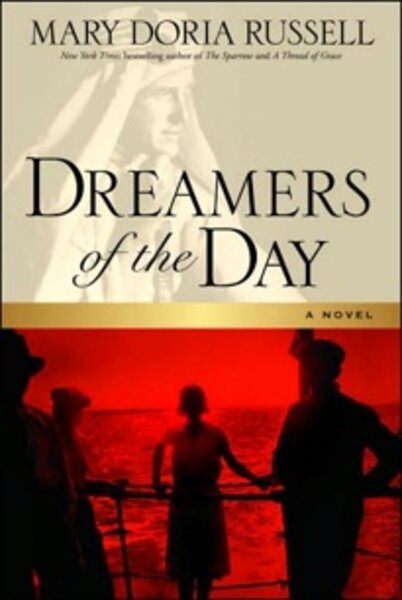

Mary Doria Russell’s fourth novel, “Dreamers of the Day,” takes its title from T.E. Lawrence’s “The Seven Pillars of Wisdom”: “[T]he dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dream with open eyes, to make it possible.”

Agnes herself isn’t much for daydreaming – it’s too painful. When a man who was courting Agnes falls in love with her pretty younger sister and whisks her off to Lebanon, “no one was less surprised than me,” she says. Agnes, meanwhile, gets to stay in Cleveland and play fun games with her mother such as “Guess what you’ve done wrong now?” If Agnes makes the mistake of asking how she’d offended her mother, Mumma replies, “I shouldn’t have to tell you, Agnes. If you loved me, you would know.”

Then the great influenza epidemic of 1919 wipes out her entire family. Reeling with grief, but finally free of her mother’s critical eye, Agnes decides to live a little. One makeover later, she’s on her way to Cairo.

“Dreamers of the Day” doesn’t shift into high gear until about 50 pages in, but patient readers will be rewarded when Agnes arrives at the Semiramis Hotel and stumbles into history. When the doorman refuses to let Agnes inside (either because of her flapper costume or because of her dachshund), the commotion attracts the attention of T.E. Lawrence and Lady Gertrude Bell, who, along with Winston Churchill and assorted other luminaries, are in Egypt to redraw the boundaries of the modern Middle East.

“Rarely has so much been decided by so few to the detriment of so many as in that fancy hotel back in 1921,” Agnes says from her vantage point in the afterlife. The parallels between British decisionmaking in 1921 and US policy in Iraq today are startling, and Russell makes the most of them. (She manages to do this without putting words in her famous characters’ mouths. Many times, she is quoting.)

The brilliant, boyish Colonel Lawrence knew Agnes’s late sister and takes Agnes under his wing. “There’s a saying here: If you think you understand Middle Eastern politics, they haven’t been explained to you properly,” he tells her.

Agnes’s outsider status makes her a useful sounding board for several of the principals. Churchill, who is always seeking a fresh audience for his oratorical brilliance, drags her with him on a painting expedition through riot-torn streets. Even Bell, who wears full-length furs while riding on a camel and is contemptuous of every woman except herself, confides in Agnes. Not coincidentally, Agnes is also befriended by a German “businessman” named Karl Weilbacher looking for inside information about the conference.

With so many outsized personalities jostling for the spotlight, Russell does a nice job of keeping Agnes center stage. (In fact, maybe too good a job – not being a Middle East policy expert, I could have used a little more background.) But Agnes holds her own with her feisty intelligence and ugly duckling charm. It’s hard to imagine a more disarming heroine than one who whispers to her dog in their hotel room, “Look, Rosie! We’re in a Palmolive ad!”

Russell clearly spared no effort with her research. Even minor characters such as Churchill’s bodyguard, a much-put-upon Scotland Yard man named Walter Thompson, are drawn from real life.

“He’s self-centered,” says Sergeant Thompson, who begged for a transfer after only six weeks on the job. “He makes the world revolve around him, and he can be an insufferable bore, but I’m starting to like the man.” Even the shopgirl who gives Agnes a makeover (and coincidentally, happens to be dating Bob Hope) really existed.

Occasionally, Russell hits her soapbox overly hard: For example, some of Karl’s more “prescient” opinings feel a tad too neat. And the head-scratching glimpse of Agnes’s afterlife that ends the novel doesn’t add a whole lot – other than to provide the chance for Napoleon Bonaparte and Civil War Gen. George McClellan to trade verbal jabs. (And, really, how many books can boast that?)

Despite the fact that many Americans have never heard of the Cairo Conference, we’re still grappling with repercussions from it 87 years later. “Dreamers of the Day” gives Agnes, and readers, ringside seats at a vital moment in history.

Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews fiction for the Monitor.