Linked

Loading...

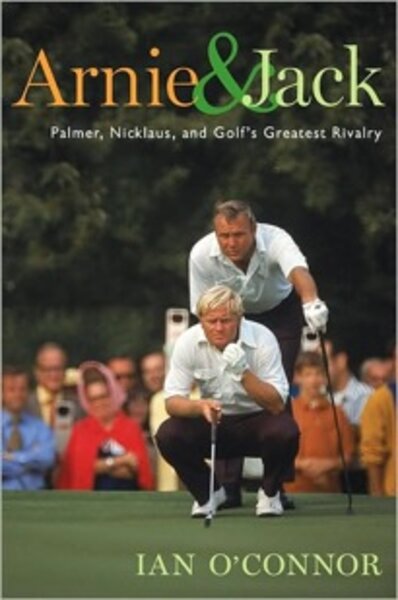

The rivalry explored in Arnie & Jack hangs palpably over the game of professional golf today.

Golf pundits wistfully, willfully want Phil Mickelson to be the Arnold Palmer of this era. Like Arnie, he’s got an army of fans. He’s the affable, approachable Everyman, with a devil-may-care way of playing. And Tiger Woods, of course, would be this generation’s Jack Nicklaus; driven, methodical, and determined to be the best ever to play the game.

But history isn’t ready to repeat itself. And after reading Ian O’Connor’s book you’ll understand why.

For five decades, the King and the Golden Bear battled each other on and off the golf course. “Arnie was the first man to prove a golfer could be an athlete, a TV star, a sex symbol all rolled up into one.... Arnie and Jack represented the perfect conflict in personality, background, and style at the perfect time – just as TV was starting to plant larger than life figures in America’s living rooms and dens,” writes O’Connor.

O’Connor traces the arc of this epic duel with more than 150 interviews, including many hours with the two protagonists and their families. O’Connor’s a good storyteller and keeps the saga moving while revealing much about the characters of both men and the evolution of the professional sport.

The rivalry begins in earnest at the 1962 US Open. Palmer has just won the Masters tournament, golf’s marquee event, for the third time and has legions of boisterous blue-collar fans who are merciless hecklers.

“ ‘Miss it! Fat Guts,’ ” was about the nicest thing being barked [at Nicklaus],” writes O’Connor. “Arnold was the King and Jack was the prince who was more like the ugly duckling,” said Frank Chirkinian, the producer of Masters telecasts. “Jack was the baby blimp with big, fat pleated trousers that made him look even bigger. He was no matinee idol.” Nicklaus seethed, but responded by beating Palmer in 1962.

It was a pattern that would continue for years. But shortly after his father died in 1969, Nicklaus began a makeover. He lost weight, grew his golden locks, and worked on his people skills. He fired his business manager Mark McCormack at IMG (who was Palmer’s manager, too), and formed a new business team under Golden Bear, Inc.

The goal? Beat Palmer off the course.

For three decades, until unseated by Michael Jordan in 1991, Palmer was the No. 1 athlete endorser. While Nicklaus never topped Palmer as a pitchman, he did surpass Palmer as a successful golf course designer.

But their business and golf games were opposites. Palmer was a conservative businessman. Nicklaus was more reckless. In the mid-1980s, he just barely avoided bankruptcy when investors bailed on two big golf community projects leaving him $150 million in debt with just $6 million a year income.

O’Connor makes clear that the competition was bitter and personal. Yet, the men’s wives, Winnie and Barbara, were close. They kept the animosity in check and prevented it from spilling over into the public arena.

Time has mellowed their rivalry. The two men no longer play professionally. But even in a friendly match, if they find themselves on the same course, each is always focused on topping the other.

David C. Scott is the Monitor’s international editor and has a closet full of swing aids.