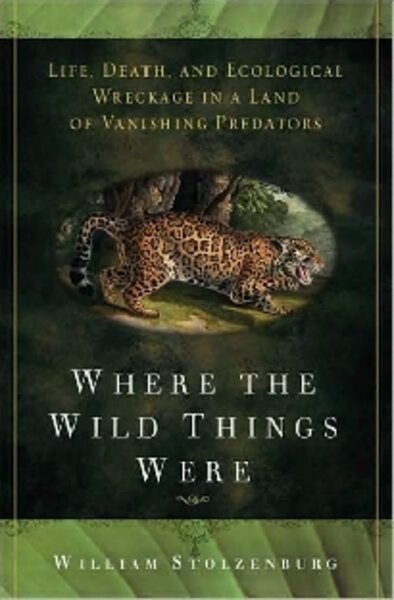

"Where the Wild Things Were"

Loading...

Where the Wild Things Were builds on one simple ecological truth: predators matter.

It should surprise no one that the best way to preserve nature is to ensure that all of its parts are in place. But the reality is that humans have long been waging a war against large carnivores – lions and tigers and bears, to name but a few. The result, says author William Stolzenburg in this absorbing and delightful work of natural history, is that we have thrown the balance of nature out of whack. The science he presents is not all new, but the scientific perspective Stolzenburg reflects will be fresh and illuminating to many readers.

From the wolves we have hunted, trapped, and poisoned out of most of the lower forty-eight states (resulting in a vegetation-destroying plague of deer, elk, and other, smaller beasts) to the sharks and other large fish we’ve all but eaten out of the sea, Stolzenburg argues that some of the most frightening animals in the world are among the most important for maintaining nature’s balance.

Predators as ‘keystone’ species

Predators are not just an important part of intact ecosystems, we learn. Often, they are true keystone species – remove the wolves from Yellowstone National Park, say, or the sea otters from a coastal kelp forest, and the whole natural edifice collapses.

A world free from predators might seem idyllic. But in a series of ecological case studies, Stolzenburg shows how removing the largest carnivores from an ecosystem lets lesser meat eaters, or newly carefree prey, come to dominate. He paints a disturbing picture of this new biological reality, from American woodlands and backyards overrun by marauding deer and raccoons to rampaging bands of meat-hungry baboons in Africa.

In doing so, he makes a strong case that we pursue our ongoing war against nature’s great meat eaters to our own detriment.

Aided by a graceful tone and a refreshing blend of scientific rigor and personal observation, Stolzenburg makes a reliable and pleasant guide through this potentially treacherous intellectual terrain.

Treacherous in part because ideas such as the large-scale reintroduction of dangerous animals are politically and scientifically sensitive to say the least; treacherous also because, to be frank, the real nuts and bolts of quantitative ecology can be astoundingly dull. Stolzenburg does a welcome job of understanding the data, methodology, and academic and political battles for us.

He clarifies without dumbing down and finds the deeper stories lurking behind the statistical models and dry language. And perhaps even more important, in revealing what might be termed the secret life of large carnivores, he helps us understand something of his own love for them.

Love for the fanged and clawed

Stolzenburg freely admits his fondness for the world’s most fearsome creatures, and while this is primarily a book of science, it is also an extended appreciation of the fanged, the clawed, and the taloned.

“All I can personally but crudely attest is that there is something fundamentally different about a land roamed by big meat-eating beasts, a sense that becomes forcefully apparent in a solitary walk through their realm,” he writes in conclusion. “And I can only believe, from somewhere deeper than any logic center of the brain, that a life of incomprehensible loneliness awaits a world where the wild things were, but are never to be again.”

“Where the Wild Things Were” is one of those rare books that provide not just an enriching story, but a new, clarifying lens through which to understand the world around us. The widespread loss of large predators is certainly not the only problem facing the natural world, but it is a significant cause of ecosystem disruptions and follow-on extinctions, and one that is often overlooked.

Make no mistake – this story is a depressing one, and the predator-centric point of view is not the only important idea in ecology. But as efforts to conserve the last bits of true wilderness intensify, and ecologists increasingly seek ways to restore ecosystems that have already been disturbed or destroyed, it is a perspective we can ill afford to ignore.

Thomas Hayden is co–author with Malcolm Potts of “Sex and War: How Biology Explains Warfare and Terrorism, and Offers a Path to a Safer World,” to be published in December.