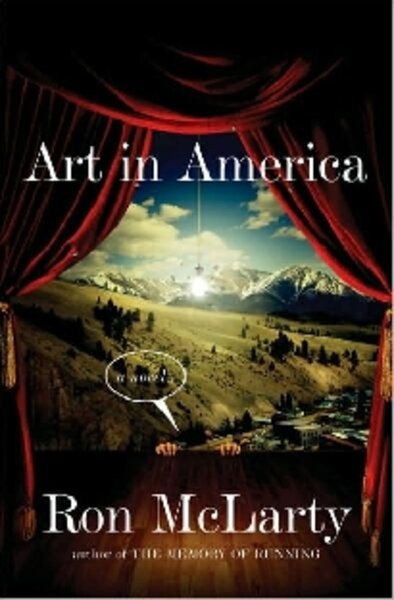

"Art in America"

Loading...

When it comes to writing, Steven Kearney is the Cal Ripken Jr. of literature – or perhaps he’s the North’s answer to Ignatius J. Reilly.

Having filled some 18,000 pages (epics, poems, free verse, plays) since 1978, the New York writer just might have outproduced Joyce Carol Oates. Of course, there is the small matter of his having never been published.

Kearney, like the heroes of Michael Chabon’s “Wonder Boys” and John Kennedy Toole’s “A Confederacy of Dunces,” is in the grip of whatever the opposite of writer’s block is. Writer-actor Ron McLarty’s Art in America opens with a summary of Kearney’s oeuvre, which includes such gems as “The Lensman of Holland,” 1,821 pages on “the adventures, successes, and tragedies of the fabulous Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, father of protozoology.”

When we first meet him, Kearney is undergoing a bit of a personal crisis – he’s just been run over by a cab, after having been evicted from his apartment and dumped by his foul-mouthed girlfriend (who also drained his checking account for good measure).

Despite the opening, “Art in America” isn’t a bitter satire. In fact, at heart it’s downright optimistic. But sweetness and optimism are a little difficult to graft onto the New York art scene (at which McLarty pokes some obvious fun), so he gets his hero out of town as soon as possible.

Kearney is offered the unlikely position of playwright-in-residence for Creedemore, Colo., where he is expected to write and direct a play about the history of the town. Once the no-longer-young-man heads west, “Art in America” really takes off.

Creedemore is undergoing its own existential crisis, courtesy of a court case brought against a nonagenarian rancher, Ticky Lettgo, who shot up the rafts of a white-water expedition that cut through his land. Also, the local sheriff has just gotten out of the hospital after having been involved in a much less comic shootout with two criminals. Both cases made headlines, and the news media and environmental and land rights activists have descended en masse.

The town itself is divided between the ranchers and folks involved in the new tourist trade. “Make no mistake, friends, the fabric of community has been worn thin in the great Weminuche wilderness,” warns Historical Society member Wilma Kirk, Kearney’s patron.

Steven arrives to find that he’s not only expected to make sense of the whole mess, but that members of the Historical Society are counting on his play to restore harmony. (Rehearsals start in three weeks. The seats already have been borrowed from the high school football stadium.) Oh, and local poet Cowboy Bob Panousus isn’t pleased that the job’s been farmed out to an outsider.

At heart, Steven’s a sincere guy with the spaced-out gaze of a daydreamer and the persistence of a day laborer. “I’m kind of a failure, although I still write, and I guess that I still write means I’m not a failure. I tell myself that,” he explains.

His take on art is so gentle and inclusive, it’s enough to send a hardened CPA running for his paintbrush: “The theory is that art, any art, is an infinite thing. There’s no time limit. Nobody to say, ‘Time’s up, you fraud, you phony, you talentless piece of nothing.’ ”

Possibly to disguise the essential sweetness of his tale, McLarty swaths his comedy in yards of profanity. (The sheriff, in particular, is impressively inventive.) And some of his comic characters – a priest who doesn’t believe in God, a radical activist who seduces college girls – aren’t exactly original.

But after the first couple chapters, “Art in America” finds a charming groove with plenty of chuckles. Those turn into snorts of hysteria once the curtain opens on Kearney’s Creedemore epic, which is of a scale and lunacy deserving an honorary Tony for funniest play never staged in real life. If you enjoy your antiheroes scruffy and your comedy topped with a dollop of Americana, buy a ticket for “Art in America.”

Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews fiction for the Monitor.