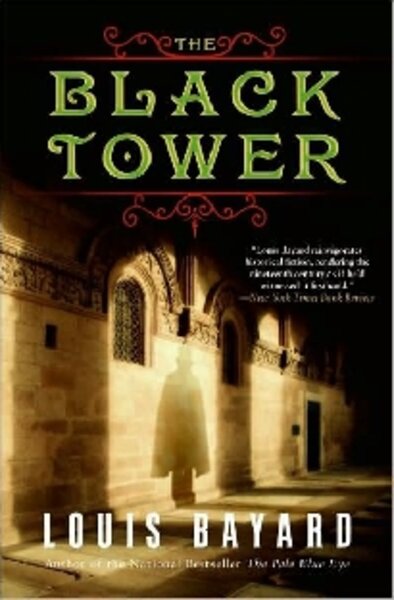

The Black Tower

One of my favorite bits of wisdom comes from P.G. Wodehouse, who opined, “I always advise people never to give advice.” Unfortunately, I’ve never been able to follow it.

Actually, the only two pearls of wisdom I can honestly say I’ve never violated come from “The Princess Bride” and Miss Piggy: “Never go in against a Sicilian when death is on the line,” and “Never eat more than you can lift.”

To this company, I add the first line of The Black Tower by Louis Bayard: “Never let your name be found in a dead man’s trousers.”

This unimpeachable counsel comes courtesy of one Hector Carpentier, a French doctor whose story serves to illustrate to readers just how right he is.

Complicating matters is the fact that Hector’s never met the dead man, Chrétien LeBlanc, who was on his way to see him when he was murdered in an alley. Carpentier discovers a link between LeBlanc and his father, a doctor who once had a very secret patient: the younger son of Marie Antoinette, Louis-Charles, who died while imprisoned in 1795 at age 10.

“Other towers, other turrets protruded from the medieval château they called the Temple (deceptively religious name!), but this tower was different. Larger – easily 60 feet in height – and black, like the inside of a chimney, and lord of all its secrets.... Whatever was in there stayed there.”

However, at least one person believes the dauphin escaped this impregnable fortress and, against all odds, managed to make it to adulthood. And they’re gunning for anyone who can provide a link to the lost prince.

Nineteenth-century novels have been good to Bayard. After turning a grown-up Tiny Tim into a bitter avenging angel, he conscripted a young Edgar Allan Poe to solve the murders at West Point in “The Pale Blue Eye.”

For “The Black Tower,” Bayard borrows again from Poe, appropriating his real-life inspiration for the very first detective story, with protagonist Eugène François Vidocq, a criminal who became one of the first private detectives and the first director of France’s Sûreté Nationale. (Among other things, Vidocq invented indelible ink and was the first to make plaster casts of footprints.)

“Legend has it that if you give Vidocq two or three of the details surrounding a given crime, he will give you back the man who did it – before you’ve had time to blink,” Carpentier says. “More than that, he’ll describe the man for you, give you his most recent address, name all his known conspirators, tell you his favorite cheese.”

Bayard is hardly the first person to see the fictional possibilities in Vidocq: In addition to serving as a model for C. Auguste Dupin, he was Victor Hugo’s inspiration for both Jean Valjean and Inspector Javert in Les Misérables.

“The Black Tower” reads more like Alexandre Dumas, though, with a little Conan Doyle mixed in.

Vidocq whirls onto the scene like Sherlock Holmes, disguised as a beggar and demanding answers. (Unlike Holmes, Vidocq has no interest in ascetics – his superhuman strength is equaled only by his appetites.)

Like Holmes, he has a doctor as his assistant and chronicler. But Carpentier isn’t a stalwart campaigner, but a broke milksop whom Vidocq press-gangs into investigating LeBlanc’s murder – once he’s convinced that Carpentier isn’t the killer. (“You’re not a fainter are you?” Vidocq asks Hector before taking him to the Paris morgue. “Well, that’s a relief. You look like one.”)

Over the next few weeks, Hector lives out an adventure story, complete with murders, flights down rat-infested drainpipes, fossilized royal beauties, and the secret that destroyed the happiness of both his parents. Bayard winds the novel ever tighter, twisting it until a reader is sure the whole thing’s going to come unsprung.

But he pulls back from the excesses that marred “The Pale Blue Eye” to pen a tale that has as much energy and cunning as the detective propelling it forward.

Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews fiction for the Monitor.