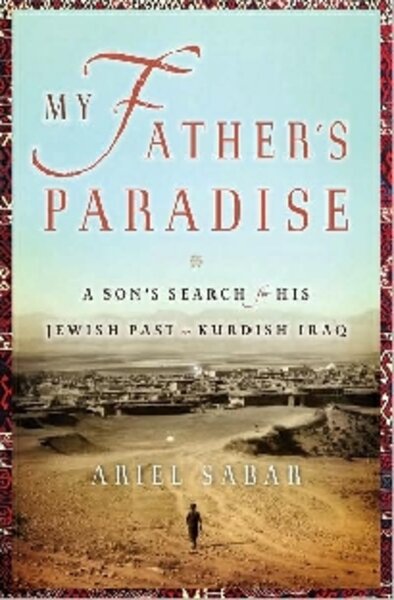

My Father's Paradise

Loading...

“Ours was a clash of civilizations, writ small,” writes Ariel Sabar of his relationship with his father. “He was ancient Kurdistan. I was 1980s L.A.”Sabar, who until recently covered the 2008 US presidential campaign for The Christian Science Monitor, is the son of an Iraqi Jew from Kurdistan, a gentle scholar forced from his homeland by politics, a man who grew up in a corner of the world so isolated that he was raised speaking the ancient Aramaic of Jesus.

If this sounds exotic or thrilling to the rest of us, it was nothing but mortifying to the youthful Sabar who was raised in Los Angeles.

“Mostly ... I kept my distance,” he writes of his father. “He lived in his world, I in mine.... [A]t some point, as a teenager, I even stopped calling him Abba or Dad. He was just ‘Yona’ ... the odd-looking, funny-talking man with strange grooming habits who lived with us and who may or may not have been my father, depending on who was asking.”

My Father’s Paradise is Sabar’s quest to reconcile an ancient past with his own life today – and to knit his father’s story to his own. It was when Sabar began his own career as a journalist and then became a father himself that the formidable challenges his father had faced began to earn his respect.

Using his journalistic skills, Sabar began to delve deeper into his father’s past. As he did, the value of his father’s uniqueness became clearer to him.

Eventually, in full pursuit of family knowledge, Sabar proposes to his father that they travel together to Zakho, in Iraqi Kurdistan, to see his father’s native village.

Not too surprisingly, Yona resists. “The height of the Iraqi insurgency against the American occupation wasn’t necessarily the ideal time for a sentimental journey by two American Jews,” he points out to his son.

Yet Yona finally relents and in 2005, the two visit Zakho, now a booming metropolis of new housing developments, factories, and Internet cafes. The trip overwhelms Yona with nostalgia and paternal pride.

But Sabar begins his story in the remote Zakho of his father’s past, where a large, Jewish, Aramaic-speaking enclave had lived in isolation and relative harmony for centuries.

This tightly knit community seemed the entire universe to Yona, who was born in 1938. But world events soon changed everything. The creation of the state of Israel in 1948, coupled with Arab hostility to its founding, forced Yona out of his paradise for good.

After Iraq and its Arab allies lost a war to Israel, virulent anti-Semitism spread all over the region. “Muslim Iraqis started eyeing their Jewish neighbors and friends with suspicion,” writes Sabar, “[and] the Iraqi parliament made Zionism a crime.” Prominent Iraqi Jews were rounded up, imprisoned, and sometimes executed. Faced with increasing persecution, Zakho’s ancient Jewish community fled Iraq for Israel.

The exile from his homeland served to focus Yona’s academic intensity: He proved to be a brilliant Aramaic scholar first at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University and later at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

But cultural isolation as an Iraqi Jew shadowed his every step. The bright promise of 1960s America also triggered an “existential depression,” brought on by Yona’s encounters with “spiritual shallowness” and endless small talk.

“America is a country of 200 million lonely people,” he wrote to his sister in Jerusalem.

Yet Yona would make his mark, becoming a leading scholar of the Aramaic language. He met and married a young Jewish woman from New Haven and began an American family life as best he could.

“Behind him were home, family, roots,” writes Sabar of his father. “Ahead, America, where, free of history, you could fly.... How could a man abandon his past and hold on to it at the same time?”

But to Ariel, as a sulking, rebellious California kid, these sorts of identity questions only meant his father was an eccentric academic (Yona taught at UCLA), a penny-pinching embarrassment.

“In a city of $300 coiffures,” writes Sabar, “my father cut his own hair,” drove a beat-up Chevette, and possessed zero fashion sense.

“I mocked [him] and I pulled away,” he recalls. “I tried to morph into the ultimate L.A. boy, some hybrid of actor, surfer, and rock ’n’ roller.”

Sabar admits his work sits somewhere between history and biography. Personal stories are unconfirmed, family mysteries remain unsolved.

And yet his own struggles to trace his family’s path draws him ever closer to the impetus that drives his father: “I saw now that his work [as an Aramaic scholar] was ... the outward expression of an intensely personal struggle to reconcile past and present.”

This must be why Sabar has resolved – with this labor of love – to educate his own young son and daughter about Zakho and to teach them the dying Aramaic language, searching “for signals about what part of our past might survive into the future.”

A reader is left with no doubt that Sabar’s children are being offered a legacy of surpassing value.

“My Father’s Paradise” is an engaging account of a wonderful, enlightening journey, a voyage with the power to move readers deeply even as it stretches across differences of culture, family, and memory.

Chuck Leddy is a freelance writer and member of the National Book Critics Circle.