The poetry of memories

Loading...

It’s inevitable to repeat yourself when you write as much – and as personally – as Donald Hall.

The 2006 US Poet Laureate and author of more than 30 books acknowledges the repetitions somewhat apologetically, but he needn’t worry: We enjoy the reminders of such beloved earlier works as “Fathers Playing Catch With Sons,” “Life Work,” and his trio of volumes about the illness and terrible loss of his wife and fellow poet Jane Kenyon nearly as much as fresh bulletins from his contemplative life.

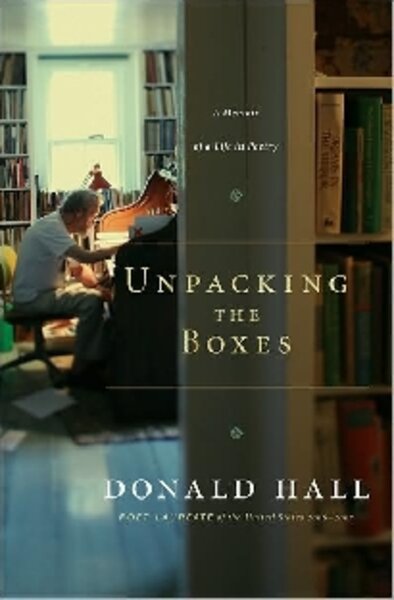

In his new memoir, Unpacking the Boxes, Hall returns to old memories and his three big themes – “Love, death, and New Hampshire.” Most remarkable, however, is the final chapter, in which he brings us up-to-date – soberly, movingly, with characteristic frankness – on his “thoughtful life on antiquity’s planet” as he approaches his 80th birthday.

He describes the effort of rising from a chair and the indignities and annoyances of deteriorating body parts.

“Gradually, on the planet of antiquity, I have become frail. Mostly I don’t feel like a codger – but I look into the eyes of others and see that they make out someone old,” he writes. Lest we find this too bleak, he assures us that the love of his children and girlfriend “sustain me, in the thin air of antiquity’s planet, where I survive to love and write poems as long as I can.”

Hall has essentially written his way through life, rising at 6 every morning for two hours of poetry composition before breakfast. He’s been a firm believer in the 20-minute refresher nap since he was a young man. For 13 years, his dawn literary endeavors were followed by a day of teaching at the University of Michigan, where he saw himself as “poetry’s evangelist preaching to convert the diffident.”

In 1975, Hall and Kenyon decamped for a life of solitude and poetry together in his maternal grandparents’ old farmhouse overlooking Kearsage Mountain in New Hampshire. She was his former student, whom he married in 1972.

Given the 19 years between them, he had every expectation that she would survive him.

In New Hampshire, he replaced teaching with freelancing, turning out articles, reviews, and as many as three or four books a year. It was a quiet, bucolic, productive existence – even when interrupted by illness: Kenyon’s depressions, his own bout with liver cancer, and then, most brutally, Kenyon’s fatal leukemia, which coincided with the loss of his 90-year-old mother in 1994.

Devastated, Hall did what he’s always done, because “making poetic lines about pain is a way of avoiding pain.”

On the subject of poaching from one’s own life, Hall quotes an article he wrote for the Hartford Courant: “Young poets sometimes fear, as they begin a life in art, that personal history may become mere material, as if one lived one’s life in order to write about it.... But as a poet ages, subject to inevitable losses, it becomes appropriate to write out of grief – appropriate, necessary, therapeutic.”

There’s much more than grief and aging here, however.

Hall gets his title – and memory prods – from the dozens of boxes that land in New Hampshire after his mother’s death. As he unloads their contents, he returns to his childhood outside New Haven, Conn., where his father’s miserable experience working in the family Brock-Hall dairy business helped fortify young Donny’s resolve at 14 to spend his life toiling at something he loved – namely, poetry.

He describes his rocky high school years at Exeter Academy, where a scathingly critical English teacher might have caused a less driven or self-assured student to rethink his literary aspirations. (Hall’s comeuppance is delectable.)

His account of his intellectual flowering at Harvard and Oxford in the company of such noteworthies as Daniel Ellsberg, Robert Bly, John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, and Thom Gunn will provide rich material for future doctoral candidates.

Why are Hall’s descriptions of a life spent mainly at a desk, arranging and rearranging words, so compelling?

Like E.B. White in his missives from Maine, Hall describes a life stripped of distractions and clutter, reduced to its most meaningful essentials – absorbing, fulfilling work, a few cherished intimates, nature’s wonders.

For most of us, it’s the road not taken – but a tempting one. Through writers like Hall, we get to experience it vicariously.

Heller McAlpin, a freelance critic in New York, is a frequent Monitor contributor.