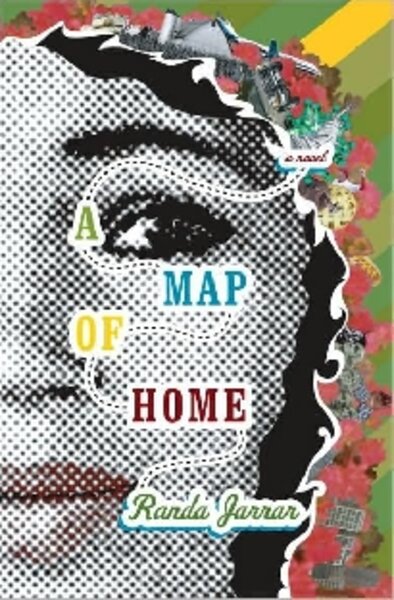

A Map of Home

Home is where the heart is. There’s no place like home. Home sweet home. Randa Jarrar takes all the sappy, beloved clichés about “where you hang your hat” and blows them to smithereens in her energizing, caustically comic debut novel, A Map of Home.

First of all, Nidali, the narrator, would be hard-pressed to pick just one spot on a map. Born in Boston, she is raised in Kuwait and Egypt. Then in 1990, Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait sends the teen and her family to Texas, where the American daughter of a Palestinian father and Greek-Egyptian mother is nonplussed to discover that her classmates regard her mixed heritage as the status quo.

In her family, home is a loaded word. “Baba said that moving was part of being Palestinian. ‘Our people carry the homeland in our souls,’ he would tell me at night as he tucked me in. ‘You can go wherever you want, but you’ll always have it in your heart.’ I’d think to myself: ‘That’s such a heavy thing to carry....’ It helped to know this when I was little, forced me to have compassion for Baba, who, obviously, had an extremely heavy soul to drag around inside such a skinny body.”

Baba is both Nidali’s staunchest cheerleader and her most vicious attacker. Take the time she enters a contest to memorize passages from the Koran. Baba, who’s intensely proud of his bright girl, is determined that she can beat all the boys. Like many a spelling-bee parent before him, he helps her in the evenings after work. However, the study aids include a wire hanger, with which he beats her when she forgets the words.

Both of Nidali’s parents are thwarted artists – her dad, who dreamed of being a poet, works as an architect, and her mother, a classically trained pianist, cannot bring herself to care about the housework and cooking that are supposed to be her lot. (“Eat poison,” she tells her daughter once when Nidali asks for a cheese sandwich.)

“Their fights were about stories, and their fights and stories were like myths, told and retold. In this way, Mama and Baba became my gods.” Tactics in her parents’ epic battles include her dad abandoning her mom in the desert and then forcing Nidali to stay up all night drawing and redrawing Palestine, “a map of home,” as he calls it.

Her father, whose sisters were forced to wed early, wants his own daughter to become a professor (and a spinster). “‘You’ll be a doctor of words, silly. Do you like words?’ I thought for a moment and then finally shrugged. ‘It depends on the word,’ I said and he laughed and said ‘Then you do.’ ”

By age 13, Nidali is getting detention to escape her accelerated classes and making out with both her first serious boyfriend and a female friend. Once in Texas, her rebellion takes on more anger and purpose as she determines that going to college out of state is the key to her sanity.

Jarrar’s tone is both comic and matter-of-fact – there’s no whining or sentimentality. And everything, even the war, is filtered through a deeply personal lens. There’s an unspoken understanding that most teens feel like the world is full of turmoil and that their parents are nuts. And there’s a frankness and courageous humor to Nidali that rarely falters. Even the flight from Kuwait has its share of absurdity: from her aunt’s much-loathed Firebird bursting into flames to the letter that Nidali composes to Saddam Hussein, explaining that his invasion has cost her boyfriend.

Jarrar also makes much of the culture clashes inherent in the immigrant experience. For example, while grocery shopping, Nidali and her mom happen upon an after-holiday sale. Her mother is overcome by their good fortune. “Oh, ze cake with ze frooooooooot,” she breathes. “The entire grocery store – its every customer, employee, bagger, butcher, stocker – is staring at us. Mama piles the fruitcakes into the cart and people are looking as though she’s loading up on hand grenades.”

It’s a shame that Jarrar didn’t tone down the profanity and the sensuality, because “A Map of Home” could have made a wonderful coming-of-age story for teens. As it stands, it’s decidedly R-rated, and with enough multilingual swearing to impress a rap artist.

Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews fiction for the Monitor.