Moving to Higher Ground

Loading...

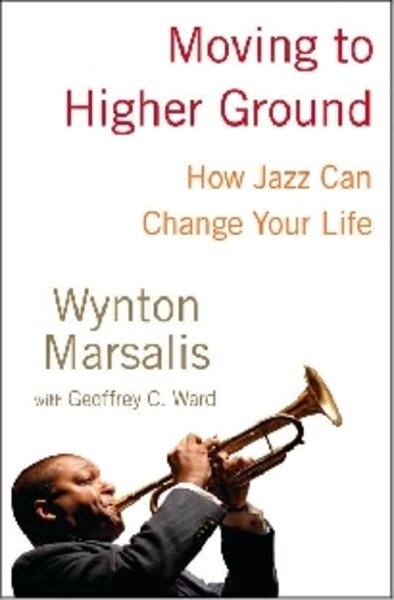

The title of Wynton Marsalis’s new book, Moving to Higher Ground: How Jazz Can Change Your Life, evokes both post-Katrina New Orleans and a self-help book, drawn together by a remarkable pedigree, the most acclaimed jazz artist of his generation.

Geoffrey W. Ward, Marsalis’s assistant with the book, is the author of a noteworthy jazz history book, a companion to the Ken Burns television documentary, “Jazz,” that included extensive commentary by Wynton Marsalis, suggesting a simpatico collaboration. The book’s back cover includes endorsements by Yo Yo Ma and Maya Angelou, so you might find this review unnecessary if you find them sanguine reviewers. If you’re curious about another point of view, read on.

Like many jazz historians and critics, I have the deepest regard for Wynton Marsalis as a remarkably eclectic and imaginative musician. But not content to be known solely for his musicianship, he has fashioned an identity as the most publicly loquacious jazz musician ever. For two decades he has positioned himself as an educator and advocate for his particular jazz slant. This book amplifies that advocate identity, one also reinforced by five previous books.

The book’s subtitle uses the phrase “your life.” This book, however, is almost entirely about Marsalis’s life and opinions about jazz. Jazz did surely change his life – and we can experience the world as a better place musically since it did. But even the most eloquent musician can falter as a spokesperson for his or her art. If this is read as an autobiography, what is its purpose? Marsalis has been thoroughly generous in giving the gist of his life story in numerous interviews, articles, and previous books. But this book is less a carefully fashioned autobiography than a jumble of personal anecdotes, or sermons with obvious, and often repeated, moral and aesthetic injunctions, all about what is and isn’t “jazz.” In fact, if you want to enjoy jazz without fussing over a precise definition of what jazz means, you – and I mean you, dear reader – will be ridiculed by Marsalis. See page 92 to discover that you’re one of those who “so successfully attacks the central nervous system of education” by not caring whether the music you like is “jazz” or not.

Yet there is a nobility in a musician of Marsalis’s artistry connecting jazz to core values such as integrity, intellectual curiosity, passionate perseverance in learning artistic craft, and democratic tolerance. All of these ideas and more are expressed with more specificity, eloquence, and wit in “The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison.” To be fair, Marsalis and Ellison had a mutually satisfying intellectual connection until Ellison’s death in 1994, and Marsalis wrote the introduction to a selection of Ellison’s essays entitled “Living with Music.” But Ellison was a painstakingly cautious writer who rarely confused his cherished musical opinions with grand public proclamations of musical truth. Marsalis is a reckless talker, as undisciplined in his rants as he is exquisitely refined and delicate in his music.

While Marsalis states in the book’s opening that “jazz teaches empathy,” empathy is curiously lacking for any musician or jazz writer who disagrees with him or whose musical direction he disdains. Not only is empathy for John Coltrane and Miles Davis in their later years missing, but anyone who enjoys hip-hop or the Rolling Stones should be prepared to stand accused, repeatedly, that they are contributing to what Marsalis identifies as a new version of a national minstrel show. And empathy is not extended to the first electric jazz bassists who cranked up their volume when performing, thus destroying for Marsalis the proper lifespan of acoustically produced, big-band jazz.

In a transparently revealing passage, Marsalis relates how the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie once chastised the young Marsalis for giving an interview where “I said all sorts of things in an indelicate manner about people selling out and ignorant jazz writers....” Dizzy responded with, “But you can’t talk like that and remain unscathed.”

Indelicacies aside, why is there such a lack of information about how to cultivate an interest in jazz, let alone how jazz can change your life? A sketchy discography includes little more than three dozen albums. There is no jazz timeline, bibliography, or new information about his own recordings. If you think jazz might change your life, go to some jazz concerts, purchase some CDs, or get a copy of an informative and open-minded book, “John Szwed’s Jazz 101: A Complete Guide to Learning and Loving Jazz.”

Norman Weinstein is the author of 'A Night in Tunisia: Imaginings of Africa in Jazz' and a contributor to the Monitor’s Arts section.