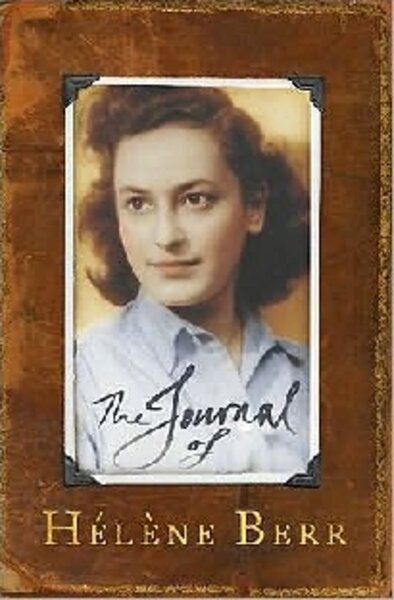

The Journal of Hélène Berr

Loading...

When The Journal of Hélène Berr was published in France early this year it became an overnight publishing sensation. Now, as the book is released in English, readers in the US will have a chance to discover why.

Hélène Berr is being called the Anne Frank of France. Like Anne Frank, she was a young Jewish woman living in Europe during the Nazi occupation who kept a diary. Unlike her younger counterpart, however, she was French and did not live in hiding. A gifted young student at the Sorbonne and daughter of a wealthy industrialist, Berr lived with her parents in their Parisian home until March 1944, when they were arrested and sent to their deaths in concentration camps.

In intelligent, heart-wrenchingly lucid prose, Berr chronicles the escalating horror of the last couple years of their lives. Berr herself is transformed from a privileged, promising youth into an adult who must grapple firsthand with horrifying questions about the existence of evil in the human experience. What elevates her account to the heroic are the clarity, calm, and compassion which she maintains throughout.

Berr’s diary begins in April 1942, when, despite the German occupation of her country, she is still living a fairly normal life. Her entries brim with enthusiasm for her family, English literature (her subject at the Sorbonne), classical music (she was also a gifted violinist), and Paris itself.

Her biggest worry at the time is whether or not she is really in love with Gérard, her absent boyfriend. Amid her confusion on this topic, she meets fellow student Jean Morawiecki, a young man of “energy and moral strength.” They fall in love and become engaged.

But Hélène’s joy is short-lived. In June, her mother tells her about the yellow star they must now wear to identify themselves as Jews. Hélène tries not to think about it.

“But I knew there was something unpleasant at the back of my mind,” she writes.

A week later, she wears the star to the Sorbonne for the first time and, “Suddenly [I] felt I was no longer myself, that everything had changed, that I had become a foreigner, as if I were in the grip of a nightmare.”

The nightmares would only multiply. Soon, her father, Raymond, is arrested. (Because of his utility to the government as a prominent chemist, the Berrs had mistakenly imagined that he would not be touched.)

“I could no longer quite understand why the whole of Paris looked so beautiful on this radiant morning in June,” a devastated Hélène writes on that day.

The Berrs are able to free Raymond by paying a bribe but they are never again free of fear.

Although many of Hélène’s Jewish friends and siblings have now fled Paris, she resolves to stay and help her parents and others. “Leaving would be an act of cowardice,” she writes. “There are also the compensations of friendship and of community in resisting.”

She eventually leaves off all connection with the Sorbonne (“I no longer belong among the studious,” she decides) and devotes herself to helping other Jews, particularly children whose parents have been arrested.

Struggling to keep fear at bay, she and her family create new routines. “In the daytime, life forms a crust on top of thought,” she writes.

But horror comes closer and closer to the Berrs. There are more arrests, more deportations, and gradually it becomes hard to imagine any but a tragic end for them.

Hélène finally decides to entrust the pages of her journal to the family’s cook, Andrée Bardiau, who is not Jewish. She instructs Bardiau to keep them and – should Hélène not survive – to give them someday to Morawiecki (who has since escaped to fight with the French resistance.)

At the war’s end, Morawiecki did receive the journal and shared a copy with the surviving members of the Berr family.

After decades of privacy, the family finally made the decision to publish Hélène’s writing as a book (a development oddly parallel to the publication last year of “Suite Française,” a novel written by Jewish author Irène Némirovsky during the Nazi occupation of France, smuggled out by family, and just published now.)

“Will anybody ever be able to understand what it was like to live through this appalling tempest?” Hélène wonders in her journal in the fall of 1943. “Will they ever acknowledge the merit ... there was in preserving a sense of fairness in the mind and softness in the heart throughout this nightmare?”

Thanks to the publication of this book, the answer to Hélène’s question is yes. Millions of readers will now be able to at least begin to comprehend and to appreciate.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor. Send comments to kehem@csps.com.