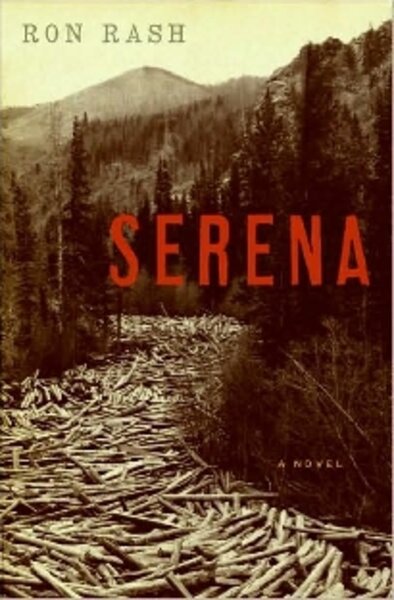

Serena

Loading...

As far as Shakespearean villains go, it’s hard to top Lady Macbeth. Ambitious, ruthless, and totally memorable – and then she unexpectedly fizzles out in Act 5. With all due admiration for Shakespeare, I never thought she seemed the type to be driven suicidal by guilt.

Author Ron Rash is apparently also skeptical about Lady M’s capacity for remorse. In his new novel, Serena, he looks at what might have happened if Lady Macbeth never went mad. Warning: Results may be harmful to the environment (not to say fatal to most of the characters in the book).

Set in the Smoky Mountains of North Carolina during the Great Depression, “Serena” opens when lumber baron George Pemberton brings his new wife, Serena, back to town.

Waiting at the train station are Rachel Harmon, the teenage girl Pemberton impregnated before he left, and her drunk, knife-wielding father. Rather than be appalled at her husband’s negligence or terrified for his safety, Serena coolly urges Pemberton to fight. After he kills the older man, she hands Harmon’s knife to Rachel and suggests she sell it, since it’s the only thing Rachel will ever get from the Pembertons.

That little matter taken care of, the Pembertons get to work clear-cutting their logging claim. There’s a certain amount of urgency, since the Secretary of the Interior is viewing the mountains with an eye to creating a national park, and the Pembertons are determined to fight this affront to unbridled capitalism by any means necessary.

The Pembertons are Ayn Rand characters taken to sociopathic extremes. Physically imposing, brave, and intelligent, Serena hunts rattlesnakes with a Berkute eagle from Mongolia (fear was slowing the men down) and can estimate better than a logging foreman how many board feet are in an ash tree. She has no use for faith, nostalgia, or charity.

“My experience has been that altruism is invariably a means to conceal one’s personal failures,” she tells Interior Secretary Albright, when discussing the local environmentalist spearheading the national park movement. (He, as it happens, drinks too much and abandoned his family.)

Serena recognizes only the present and demands the same of her husband. As a teenager, Serena survived the illness that wiped out the rest of her family.

When one of Pemberton’s business partners says he’d like to hear more about the father who taught her the logging business, she seems baffled. “ ‘Why?’ Serena said, as if puzzled. ‘He’s dead now and of no use to any of us.’ ”

Also of no use, in Serena’s estimation, is Pemberton’s business partner Buchanan, who is inclined to offer workers a dime a day raise and who isn’t opposed to being bought out by the government. Serena urges Pemberton to take care of the matter in the most expeditious manner possible.

Then an event occurs that causes Serena to turn her implacable attention back to Rachel and her baby and the bodies really start piling up.

“Serena” manages to be terrifying without ever turning graphic, as Rash matter-of-factly lays out his characters’ course. Most of the murders occur off the page and are reported back to the logging camp, but are no less chilling for that.

Rash supplies plenty of grim wit, courtesy of his Greek chorus, a group of loggers led by one Snipes, who are trying to survive a job that was dangerous enough before their boss got married. In addition to falling trees, logjams, axes and saws, and record cold, there are the rattlers and a panther that is rumored to be stalking the mountains.

No one’s ever seen it, but, Snipes points out, there are all kinds of things people can’t see that are there. “Well, They’s love, that’s one. And courage. You can’t see neither of them, but they’re real. And air of course. That’s one of your most important examples. You wouldn’t be alive a minute if there wasn’t air, but nobody’s ever seen a single speck of it.’ ”

“ ‘And chiggers,’ Stewart said helpfully. ‘You’ll never see one but you get into a mess of them and you’ll be itching for a week.’ ”

The bestseller lists are filled with stories of sociopaths on the loose and few of them qualify for greatness. Despite the darkness of the plot, Rash fills “Serena” with a deep humanity and some downright terrific writing. His themes of greed and the destruction wrought by unfettered capitalism couldn’t be more timely.

But it’s his patient crafting of life during a bygone era that will delight readers. His evocation of the harsh conditions, where the only way to survive was to destroy the beauty surrounding you, is powerful, and his dialogue is a delight.

Buchanan, who, before his unfortunate hunting accident, liked to write down colorful mountain sayings, would be scribbling nonstop.

Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews fiction for the Monitor.