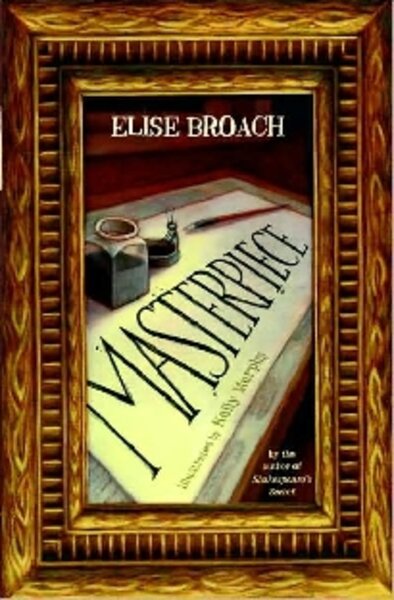

Masterpiece

Loading...

If you thought E.B. White’s Charlotte was an artist, wait until you meet Marvin. He’s the heroic beetle at the center of Masterpiece, Elise Broach’s new mystery, and if you’re squirming at the combination of “heroic” and “beetle” then get a load of Marvin’s talent.

Marvin’s a pretty ordinary bug when “Masterpiece” opens. He spends his days watching the goings-on in the Pompadays’ New York City apartment. His main enemies are stiletto heels and insect-averse humans.

But when 11-year-old James Pompaday leaves open his birthday present – a bottle of ink, gifted to him by his artist father – Marvin finds himself thrust into a world of forgeries, art heists, and FBI operatives.

Things start out innocently enough when Marvin, drawn to the ink, discovers an artistic talent that rivals that of Albrecht Dürer, a Renaissance artist known for his detailed miniatures.

James receives credit for Marvin’s drawing, but not before boy and bug form an unlikely friendship – and a complex (if unwitting) deception.

The real intrigue begins when a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art asks James to copy a Dürer piece. It’s part of a top-secret plan to get a stolen Dürer back, but in true art-heist fashion, nothing goes as planned.

And though Marvin’s just a tiny beetle caught in an elaborate web of trickery and danger, he vows to save the masterpiece – with James’s help, of course.

With “Masterpiece,’ Broach makes another welcome contribution to the art-mysteries-for-kids genre recently populated by offerings from Blue Balliett (“The Calder Game,” “Chasing Vermeer.”)And like any good title of this type, “Masterpiece” will keep readers guessing – and turning pages. Broach’s pacing is sublime; you can’t help speeding on to the next chapter.

But “Masterpiece” also bridges the gap between the commercial and the literary. Rather than sacrifice character development for intrigue, the story allows both to develop organically. The characters’ emotions feel true, their moral dilemmas real.

And the pacing benefits, rather than suffers, from Broach’s “time-out” moments: a philosophical reverie on virtue, the cottony sky at dusk.

In addition, Broach doesn’t shy away from conversations about art. In a less-capable writer’s hands, these moments could feel didactic or leaden. Instead, education itself becomes part of the story: the nature of the Dürer drawings, what they stand for, helps to inform and explain the characters’ motivations.

For Marvin, the motivation is twofold – helping a friend and drawing close to the master he dreams of emulating. Both impulses are thoroughly believable. Marvin isn’t zany enough (or big enough) to invoke the bugs in Roald Dahl’s “James and the Giant Peach.” But the best of all human-animal friendships are echoed here: “Charlotte’s Web,” “The Cricket in Times Square,” even Sterling North’s “Rascal.”

Which is to say that in spite of his family’s misgivings (and in spite of strict codes of behavior relating to human-beetle relationships), Marvin is determined to stand by James. In many instances, this means risking the displeasure of his relatives – not to mention his own life.

It also leads to thrilling moments of suspense – and laugh-out-loud moments of hilarity. For example, when you’re a beetle who can neither write nor speak, how do you communicate that you’ve found a stolen painting? And once the painting has been recovered, how do you keep those humans from accidentally putting it back into the hands of the thief?

I won’t give away the ending here, but I will venture that even skeptical readers will have a hard time not calling Marvin heroic by the end of this tale. Heroic because of his bravery and cunning, sure. But more so because of what Marvin brings out in James – and what both boy and beetle learn about friendship in the process.

Jenny Sawyer regularly reviews children's literature for the Monitor.