Reviews of three biographies for children

Loading...

Question: What do William Carlos Williams, L. Frank Baum, and the women of the American Revolution have in common? If you answered, “Their lives make good stories,” you’d be right. Three children’s authors thought so, too.

A word up front to book-buying adults: Don’t be put off by these stories’ picture-book format. There’s nothing babyish about any of these three new biographies aimed at young readers. Instead, the format allows for a multiple-level reading experience. Which means younger readers will enjoy the vibrant, detailed illustrations, while older readers (or history buffs) will delight in the little-known facts and literary allusions.

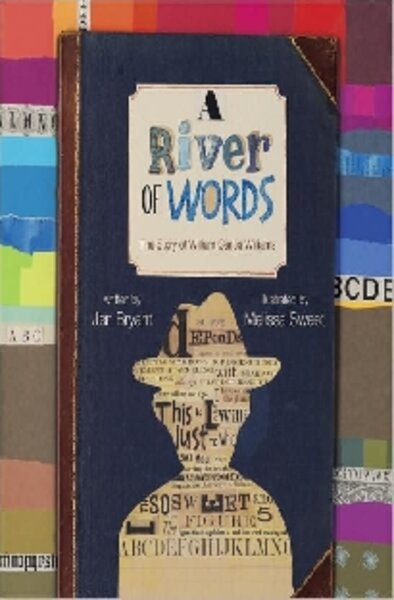

In A River of Words, written by Jen Bryant and illustrated by Melissa Sweet, allusions abound both in text and pictures. Sweet’s collage-style illustrations are especially rich, combining period paraphernalia with elements of the natural world that inspired Williams’s poetry.

But Williams-the-poet isn’t the man that readers first meet. The story opens in Rutherford, N.J., where little Willie is playing baseball and running races with friends. His long ambles in the wilds of Rutherford give us a hint of what’s to come.

“Poetry suited Willie,” writes Bryant of the teenage Williams. But financially, being a poet was an impractical career choice. In college, Williams pursued medicine, and later, he returned to his hometown where he became a busy family physician.

And yet, rather than detract from his poetry, Bryant and Sweet show how Williams’s attention to detail – both in his practice, and in the world around him – simply provided more fodder for his writing.

In a particularly poignant rendering, several lines from Williams’s poem “Complaint” are pictured scribbled on a notepad: “They call me and I go ... The door opens / I smile, enter....” Excerpts of Williams’s poetry provide additional context, and interested young poets can find the titles of Williams’s collections in a reading list provided by the author.

While Williams’s work may be unknown to most children, those who pick up The Road to Oz, written by Kathleen Krull and illustrated by Kevin Hawkes, will likely already be familiar with L. Frank Baum’s most famous work. Sharp-eyed readers will also spot references to the story of the girl from Kansas who trekked to the Emerald city – even on the first page of this colorful biography.

“It was 1860s America, rural New York to be exact, and Lyman Frank Baum’s family was rich,” writes Krull in her opening. “Rosebushes dotted their emerald-green front yard. Hundreds of rosebushes in glimmering-jewel colors.”

As the story progresses, a scarecrow watches from a neighboring field, and a grown-up Baum pedals with his family through fields of poppies.

But it was a winding road to Oz, and for Baum – much like for Dorothy and her friends – it’s the journey that offers the real fun and suspense in the story. Krull’s narrative follows Baum through his years of impractical dreaming as a playwright, chicken-breeder, and traveling china salesman, to his years of, well, impractical dreaming, but now, finally, as a celebrated author.

What emerges along the way is a portrait of a risk-taker whose varied life experiences helped him create one of the most well-loved classics in the children’s literature canon.

The women and girls of Laurie Halse Anderson’s Independent Dames (illustrated by Matt Faulkner) would relate to Baum’s risk-taking. Anderson’s spirited text chronicles the little-known patriotic exploits of the under-represented sex – from 9-year-old Susan Boudinot, who threw her English tea out the window, to Eliza Wilkinson, a South Carolina widow who stole from the British and smuggled supplies to American troops.

Forget damsels in distress; there are no shrinking violets in this story. Women wield guns, dress as men, run printing businesses, and work as blacksmiths. They protect their homes from the British and get the country back on its feet once the war is over.

Faulkner’s illustrations give a sense of time and place, while still doing justice to a group of dames who sometimes look more at home pointing rifles than wearing petticoats. And Anderson’s careful research brings to life a collection of individuals who shouldn’t be relegated to a footnote in a history book.

Which leads me to one other thing that the figures in all three of these titles have in common: Their stories deserve a place on any child’s bookshelf. And on any childlike adult’s, as well.

Jenny Sawyer regularly reviews children’s books for the Monitor.