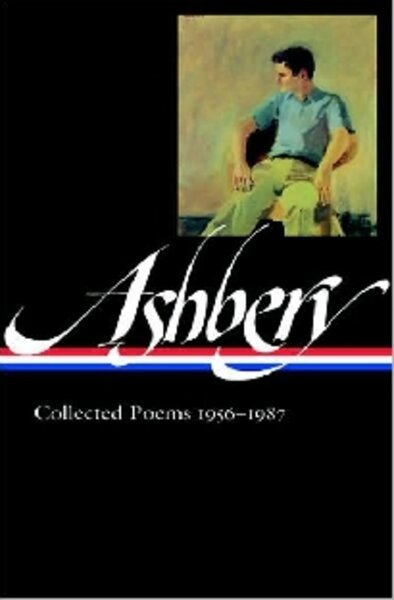

Ashbery: Collected Poems 1956-1987

Loading...

If John Ashbery’s widely acclaimed status in literary circles as “the great living American poet” were ever in doubt, the recent publication of his Collected Poems 1956-1987 as part of the prestigious Library of America series would serve to cement that stature.

This is the first time this publisher has honored a preeminent living poet. Volume One of a projected two-volume set, this almost 1,000-page collection reprints Ashbery’s first dozen books and also includes 60 previous unpublished poems from the past 40 years.

Why is this publication of the work of this spry and productive 80-year-old author astonishing? This recognition occurs amid a general consensus among even his admirers that Ashbery’s poetry is “difficult” – baroquely complicated and obscure.

Poetry has always been a tough sell in the marketplace, except for those poets classified as “accessible.”

The thought of an intensely abstruse poet getting all of this attention and a loyal readership is mind-boggling.

But Ashbery has always rejected charges that his poetry is mysteriously elusive – as does this reviewer.

“Despite what everyone said, I always thought that there was something simple and penetrable in my poetry, screaming to be let out,” Ashbery remarked to a London newspaper interviewer.

For proof, consider the opening of “The Instruction Manual” from Ashbery’s 1956 collection, “Some Trees”:

As I sit looking out of the window of the building

I wish I did not have to write the instruction manual on the

Uses of a new metal.

I look down into the street and see people, each walking with

An inner peace,

And envy them – they are so far away from me!

And this understandable distraction from a menial task leads to:

And, as my way is, I began to dream, resting my elbows on

the desk and leaning out the window a little,

Of dim Guadalajara! City of rose-colored flowers!

I’m quoting this early poem at length because Ashbery has rarely deviated in purpose from his first works. The poem’s subject is the poet’s imaginative reverie, moving from the most mundane and prosaic circumstances to flights of lyrical poetic imagination that make the mundane enticingly exotic.

Twenty-three years later in his collection “As We Know,” Ashbery still invites his readers to join him in an imaginative odyssey transforming the daily grind into a daily dream-like reality:

But it is the same thing we are all seeing,

Our world. Go after it,

Go get it boy, says the man holding the stick.

Eat, says the hunger, and we plunge blindly in again....

Unlike poetry that comments on life’s absurdities with bemusement (Billy Collins) or gazes upon nature as a mirror of human nature (Mary Oliver), Ashbery’s work takes as its subject the way that poetic imagination constructs our daily sense of meaningful reality despite the world’s “great blooming, buzzing confusion” (to quote William James).

What seems obscure in Ashbery’s poetry is the way he allows himself – and encourages his readers – to run the rapids of his capacious, fantastic, stream-of-consciousness style, which is full of unexpected shifts (not unlike the unpredictable twists and turns of our everyday lives).

Once any reader is willing “to go along for the ride” – to follow Ashbery’s meandering pathways of thought – reading his work becomes an entertaining, tragicomic, imaginative experience.

Ashbery seems to challenge us: How much can we mine our daily routines for fantastic imagery that can be animated, even as the view from a New York office building into a street becomes (in imagination) the unfolding of a Mexican street festival?

Reading Ashbery involves the ability to make sudden shifts between slangy and literary language, between rational analysis and irrational intuition, and to fuse seemingly unrelated images from paintings, film, and daily life. His poems seem to narrate stories – but they are stories constantly interrupted by paradoxes and contradictions, all part of a storytelling sensibility that loves unsolved and unsolvable mysteries.

Call this volume of Ashbery’s work a training guide for imaginative calisthenics.

Norman Weinstein is a contributor to the Monitor’s Arts and Culture section.