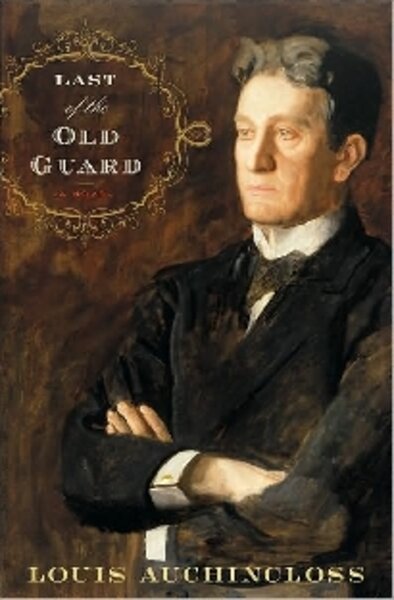

Last of the Old Guard

Loading...

Some people make the rest of us look like idlers. Case in point: Louis Auchincloss, who has written, on average, a book a year for six decades – even while practicing trust and estate law full-time for more than 40 of those years.

At 91, he’s produced his 65th book overall and 47th volume of fiction, Last of the Old Guard. The title refers to Ernest Saunders, a chilly New York attorney whose greatest passion is the law firm he founded with a Harvard classmate in 1883.

But Auchincloss, who was honored as a Living Landmark by the New York Landmarks Conservancy back in 2000, may well feel like the last of the old guard himself.

There’s something oddly comforting about reading this patrician novelist of manners, successor to Edith Wharton. You know, to a certain degree, what you’ll be served – rather like eating at an exclusive social club.

The food is rarely exciting, but it’s never alarming, either, and it’s impeccably presented. Manners are genteel, language is as proper and crisp as white linen napkins, and everyone is educated and well-heeled. It all feels like a throwback to a more gracious time.

Wisely, Auchincloss doesn’t attempt to set “Old Guard” in the frenetic, often rude world of text messaging and blogging. Instead, he rolls the clock back more than a century, trying to capture the decades between when Ernest Saunders and Adrian Suydam formed their partnership during the unbridled growth of the late 19th century and Ernest’s death, at 84, in 1942. Historic benchmarks along the way include Teddy Roosevelt’s administration, World War I, and the Great Depression.

Even so, the timing often seems off by about 50 years, with anachronisms such as casual Fridays and female associates cropping up in the 1930s.

Throughout his long writing career, Auchincloss’s abiding subject has been moral standards – the tenets by which people choose to live. The old-fashioned virtues of honor and dignity matter a great deal to him – much more than pedigree.

So, too, does the law. Like many of his books, “Old Guard” concerns a Wall Street corporate law firm and is narrated in the first person.

Two years after the death of his partner, Addie Suydam sets out to profile this brilliant but flawed human being, making use of material that wasn’t suitable for his recently completed official history of their firm. Unfortunately, long confessional letters from Ernest, his wife, and a former partner sometimes strain credulity and come across as a somewhat creaky narrative device.

Central to Addie’s account is his worry that he’s been a pushover to his dominating partner, whose specialty is fighting antitrust cases.

“What I am concerned with,” he states, “is the history of my own spiritual development and the evaluation of what Ernest and I have accomplished in our joint lives, as opposed to what we might have.”

A mixed portrait of Ernest emerges, indifferent to “the tumults of human passion” and content to confine himself “to the serene pastures of moderation and common sense.” One exception was his attachment to his son, a relationship that ends unhappily. His most successful connection is with Addie.

Auchincloss’s unsentimental autocrat may remind readers of Jane Gardam’s crusty retired barrister from “Old Filth.”

But whereas Gardam’s stiff-lipped raj orphan was endearing in his fusty detachment, Auchincloss’s Saunders is a belligerent force to be reckoned with. He recognizes his limitations unapologetically and, interestingly, often ends up doing the right thing – even if for the wrong, selfish reasons.

Central to the yin-yang push-pull of Addie’s relationship with Ernest is their fundamental disagreement about the role of government in protecting its citizens – not just militarily, but economically.

Ernest, who benefits richly from laissez-faire policies that enable industrialists to amass unprecedented fortunes, opposes government intervention and FDR’s New Deal. He comments about those suffering during the Depression, “They’ve been living too high on the cob. It was time for a chastening.”

His more humane partner wonders, however, if inequities are “the inevitable price of rapid industrial growth” and whether it’s their “moral duty to correct flagrant injustices.”

Auchincloss could well be writing about debates taking place today about imposing new government regulations on the financial industry. So, despite its focus on a bygone standard-bearer of a bygone era, “Last of the Old Guard” manages to surprise us with its timely relevance.

Heller McAlpin, a freelance critic in New York, is a frequent Monitor contributor.