Mr. Timothy

Loading...

[The Monitor occasionally reprints older book reviews from its archives. This review originally ran on Dec. 16, 2003.] Poor Ebenezer Scrooge. Somebody's always trying to pick his pocket.

If it's not those pesky charities, it's Bob Cratchit asking to get off on Dec. 25 - " the whole day!" Pirated copies of "The Christmas Carol" appeared in England before it was two weeks old. American publishers stole it as soon as the steamer arrived in New York.

Written quickly in financial and artistic desperation just before Christmas in 1843, Dickens's classic sold phenomenally, but consumed its own profits in printing and legal costs.

Everybody, it seems, was able to benefit from Scrooge except his creator. Bah, humbug!

The story wasn't even a year old before some satirical wag brought out a sequel. And the sequels have been haunting Scrooge ever since.

This year's appearance, fortunately, is far more than "an undigested bit of beef," as the unreformed miser would complain. It's a fantastic Victorian thriller starring Tiny Tim, who's "not so tiny any more." He's not so crippled any more either, or so treacly.

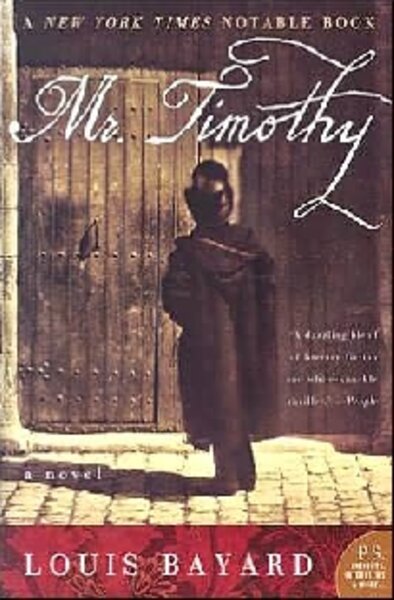

In fact, the narrator of Louis Bayard's engaging novel Mr. Timothy is now 23 years old and supporting himself by teaching a London madam how to read. That's hardly the most reputable position, of course, but Bayard reminds us that mid-19th century London was an unseemly place, its streets clogged with desperately poor people, thugs, and prostitutes.

The miraculous intervention of Mr. Scrooge after "the change" helped Tim escape an early death, but his spirit remains hobbled.

We learn that long dependence on Uncle 'Neezer's generosity saved the family from poverty, but couldn't protect them from other tragedies or more subtle humiliations. Most of the Cratchit children are now dead - or vanished, disgusted with their dependence or resentful that Scrooge's money couldn't somehow do more to transform them.

Indeed, what's best about this novel has nothing to do with what makes it such an exciting story. Tim is still untangling his complicated grief over his father's death, seeing his ghost everywhere. In letters to the late Bob Cratchit, Tim recounts the discomfort of being the subject of his father's sentimental visions of how a little crippled boy should act.

"It was a bit like a serialized novel," he notes with a touch of poststructural humor.

"I couldn't recall even thinking the words you assigned to me," he writes to his father. "But those were the words I was assigned, and so they became my words, and you became my teller."

Desperate to please his father, he practiced the dewy look, the hopeful sigh, the pitiful cheeriness, contorting his character more surely than that mysterious illness could ever twist his legs.

But now, with both his parents gone and the Cratchit family dispersed, Tim must be his own narrator in a story of his own making.

When we meet him, the plot of his new life has taken a decidedly dark turn. Little girls are showing up dead. He finds one in an alley.

Another is dragged from the bottom of the Thames. The ghost of a third passes by his window. They all sport a creepy insignia burned into their shoulders, the letter G with raptorial eyes. So, when he spots a little waif alive on the street, he's overwhelmed by a desire to warn her, to save her from the terrors of city life.

With his limping gait, he never could have caught up with her.

Fortunately, a little entrepreneur named Colin the Melodious, age 10, offers his detective and delivery services. Together they track down Philomela, a 10-year-old orphan newly arrived from Italy. She speaks almost no English, but she can convey her terror about some ghastly torture she's endured.

No sooner does Tim convince her to trust him than they're attacked by a knife-wielding policeman, and she's kidnapped, throwing Tim and his ribald little sidekick into daring rescues, near misses, and hair-raising escapes from a band of unspeakable villains.

There's one particularly wild carriage chase that's so furious I worried I'd fall off.

Along the way, Bayard draws in a host of Dickensian characters (what other kind would do?), including a cameo appearance by Scrooge himself, now besotted in the glow of Christmas cheer year round and dedicated to charity and his fungi collection.

Tim's trial for solicitation - hold on, he's completely innocent - would fit comfortably among any number of Dickens's witty satires about the court system. And Tim's boss, Mrs. Sharpe, with her thirst for classic literature and her acumen in the world's oldest profession, fleshes out the cast wonderfully.

The ending is as much Edgar Allan Poe as Mission Impossible, a plot with enough trap doors and false bottoms to show just how much fun a ripping thriller with eggnog can be.

But what's particularly satisfying is that beneath these waves of adventure rests a truly moving meditation on grief and reconciliation. Tim doesn't need anyone to torment him from beyond the grave; he's doing that well all by himself.

But the salvation he eventually earns is enough to choke up even readers who recall his sappy boyhood benedictions with a groan.

Readers haunted by Dickens's original will also want to get "The Annotated Christmas Carol," edited by Michael Hearn (W.W. Norton, $29.95). Like Hearn's annotated versions of "The Wizard of Oz" and "Huckleberry Finn," this large gift book contains a long introduction about the story's creation and reception, an enormous collection of illustrations, and voluminous footnotes.

God bless them, every one!

Ron Charles was the Monitor's book editor.