From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776

Loading...

As the world awaits the historic inauguration of Barack Obama, there are daily reminders of the far-reaching impact of the foreign policy of the United States. The extraordinary global interest in the 2008 US presidential campaign and the universal excitement that followed the election of the first African-American president demonstrate the degree to which the world’s peoples understand that decisions made by American policymakers can have profound consequences, for better or worse, on the fate of nations.

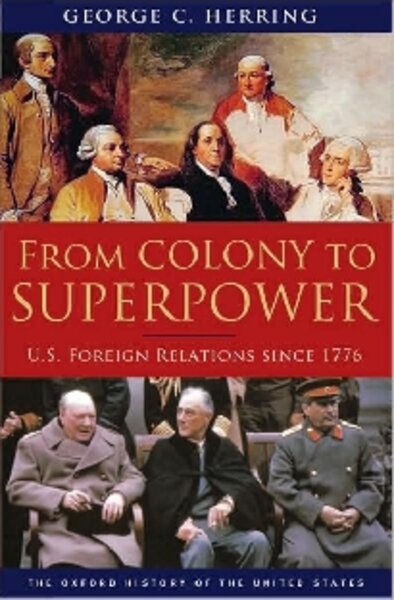

Those decisions are the focus of From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776, a sweeping and lucid history by George Herring, an emeritus professor at the University of Kentucky. This authoritative work is destined to grace the bookshelves not only of scholars, but also of nonspecialists who want to understand how the US has engaged the world from the American Revolution to the administration of George W. Bush.

But be forewarned: Those bookshelves had better be sturdy, for Herring’s book is more than 1,000 pages long.

Herring begins this volume, the latest installment in the “Oxford History of the United States” series, with a luminous chapter highlighting the way in which a variety of factors have shaped American diplomacy since the Republic’s founding.

Among the formative elements Herring discusses are the pursuit of economic self-interest; a belief in white supremacy; unilateralism; a democratic political system; and, finally, the American belief that the US was driven by a providential mission.

‘A city set upon a hill’

Indeed, Herring writes, Americans have long imagined themselves a “chosen people,” and have been convinced of their exceptional nature. As early as John Winthrop’s assertion that the Massachusetts Bay Colony was a “city upon a hill,” those who came to North America felt they were more virtuous than any other people on earth.

And lest one doubt the lasting power of this idea, Herring reminds us that Ronald Reagan regularly invoked Winthrop’s 17th-century words to convince Americans that they had a special role to play in world politics.

President George W. Bush has also often used such exceptionalist language to explain the zealous foreign policy of the past eight years.

In this authoritative study, Herring deftly blends narrative and analysis, and helps the reader understand what happened and why.

Particularly effective is the way he traces the trajectory of America’s emergence as a world power.

Herring carefully examines this unfolding story from the imperial impulse marked by the Spanish-American War in 1898 to the articulation of Wilsonian principles during World War I (Woodrow Wilson believed deeply in America’s special mission) on through the great transformation brought about by World War II.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the US would never again hesitate to become energetically involved in world politics.

If Franklin Roosevelt moved cautiously toward war before Dec. 7, 1941, his successor showed little reluctance to pursue an activist foreign policy that claimed virtually every corner of the earth as vital to the security of the US.

Whether confronting developments in Iran, Greece, Turkey, or Korea, Harry Truman expanded the notion of American interests dramatically and his foreign policy marked a fundamental break from what had come before.

Although even in its earliest days America was never isolated from the world, Herring points out that in the late 1940s, with the start of the cold war, the US assumed the mantle of global leadership.

Consumed by a pathological and, Herring believes, exaggerated fear of communism, America shed whatever tendency it once had for keeping the world at arm’s length.

The end of the cold war

In an incisive chapter on the conclusion of the cold war, Herring rejects the claim that Reagan was responsible for winning the conflict that had distorted world politics for nearly five decades. Reagan played an “important role” in ending the struggle, Herring notes, but Mikhail Gorbachev, the “remarkable” Soviet leader, took the “dramatic steps” necessary to conclude the global competition.

In 1862, amid a grave domestic crisis, a president from Illinois told the American people that it was necessary to “think anew, and act anew.”

As another man from Illinois prepares to become president and ponders how best to engage the world in the 21st century, he would do well to heed the words of Abraham Lincoln.

Jonathan Rosenberg teaches US history at Hunter College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.