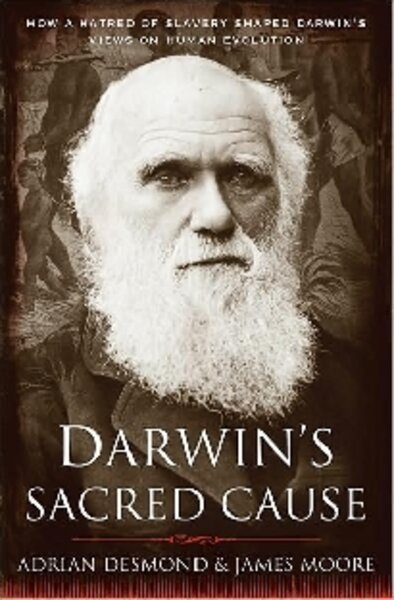

Darwin's Sacred Cause

Loading...

Who would have guessed it? The bogeyman actually had a heart of gold. Two hundred years after his birth, and 150 years after the publication of his book that would appall much of the Christian world, Charles Darwin is a specimen under a microscope himself, the subject of a slew of new books and articles.

A candidate for the most insightful, and perhaps the most radical, is Darwin’s Sacred Cause. In this thorough and highly researched, yet readable and even entertaining book, Darwin scholars Adrian Desmond and James Moore seek to humanize the father of evolutionary theory. His drive to uncover a single common ancestor for humans, they say, was prompted squarely by his opposition to the great social evil of his day: slavery.

Darwin, ironically, shared that passion with abolitionist Christians, with both declaring the brotherhood and essential equality of all humans, regardless of race. While Christians found their justification in the Bible – all humans as the children of one God – Darwin sought evidence in nature, gleaning it from years of collected data in the field and piecing together the meaning, a process that persuaded him that humans were indeed a single species derived from a common ancestor.

Those ideas were not universally held in the mid-19th century, either among Christians or scholars. Darwin’s scientific contemporaries were proposing that mankind was made up of from two to 63 distinctly different species: Louis Agassiz at Harvard University, one of the most respected scientists of the day, thought there were eight.

Such conclusions led some to the belief that human rights didn’t extend to Africans, who could be treated as lesser beings.

“Destitute of morality, incapable of civilization, black people were hardly above the ape themselves,” was a common planter attitude in the US South and Latin America, the authors say.

A compassionate upbringing

During Darwin’s boyhood, his devoutly religious older sisters “taught him respect for life and sympathy for God’s creatures,” Desmond and Moore write. He learned to dip worms to be used as fish bait in brine, a humane killing that would spare them suffering on the hook.

“Compassion and anti-cruelty were paramount in the family,” the authors write. Darwin “devoured” antislavery pamphlets and expressed great admiration for the American abolitionist agitator William Lloyd Garrison.

The great naturalist later saw the slave trade firsthand in his years of travel. He probably met more dark-skinned people in places such as South America and Cape Verde than had almost anyone he knew back home in England.

“I was told before leaving England, that after living in Slave countries all my opinions would be altered,” Darwin wrote.

“[T]he only alteration I am aware of is forming a much higher estimate of the Negros [sic] character, – it is impossible to see a negro & not feel kindly towards him....”

In Brazil, Darwin was deeply affected after hearing the screams of a slave being tortured on the other side of a wall and realizing with anger and frustration that he had neither the ability, nor legal standing, to interfere. After that, the sound of any distant scream “would always bring back memories of that tortured slave,” the authors say.

Darwin never publicly campaigned for abolition, granted in 1833 in the British empire and in the US by Abraham Lincoln at the height of the Civil War in 1862. He’s been seen as a cool recluse, more fascinated with the lives of butterflies, beetles, and orchids than those of fellow humans.

But once you look for them, his views on the brotherhood of man permeate his work, Desmond and Moore conclude. For example, phrenology, or craniology – the reading of skull shapes and bumps to determine racial origin, as well as caste or social position – was a scientific fad of his time. (Phrenologists always managed to put their ideal of Anglo-Saxon skull shapes at the top of the pecking order of human species.)

Darwin and the brotherhood of man

This attempt to stratify humanity through physical differences never appealed to Darwin. Unlike many scientists and explorers of his day, he never sent a single human skull home for examination.

By taking a fresh look at Darwin’s unpublished family letters, his notebooks and marginal scribblings, even ship’s logs and lists of books he read, the authors find a different Darwin emerging. “What a proud thing for England, if she is the first European nation which utterly abolishes [slavery],” Darwin scribbled early in his career.

This idea of the “brotherhood” of humans underpins Darwin’s work, write Desmond and Moore. “It was there in his first musings on evolution in 1837.” It was the “moral fire that fueled his strange, out-of-character obsession with human origins.”

The authentic Darwin, the authors conclude, is “a man more sympathetic than creationists find acceptable, more morally committed than scientists would allow.”

Gregory M. Lamb is on the Monitor staff.