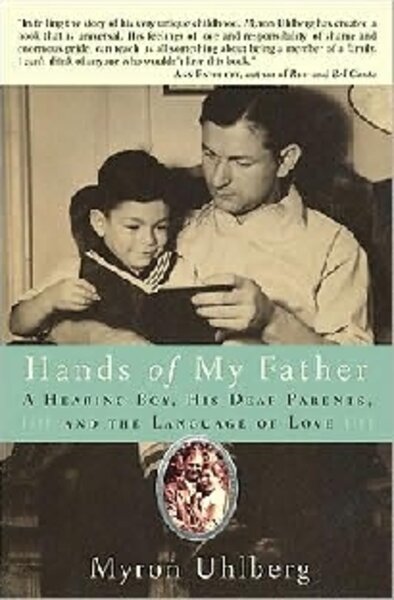

Hands of My Father

Loading...

Say “language” and most people think of the rich intricacies of written and spoken words. But Myron Uhlberg’s first language took a different form. Before he could speak or write, he learned American Sign Language, gesturing with his young hands to communicate with his mother and father, who were deaf.

His first message was “I love you.”

As Uhlberg explains in his deeply moving memoir, Hands of My Father, he straddled two worlds as he grew up in the 1940s and 1950s – one profoundly silent, belonging to his parents, the other rich with sound. From the age of 6, he functioned as a miniature adult, becoming his parents’ designated ears and voice as he communicated with neighbors, merchants, doctors, and waiters.

At the poultry shop near their Brooklyn apartment, for example, his father, Louis, would sign to the little boy, “Tell Mr. Herman we want a fat chicken today.”

His grandmother defined the child’s role reversal bluntly, saying, “You must always take care of your parents.” Only by escaping to the roof of their apartment building, away from family duties and taunting playmates, could he dream of being a “normal kid.”

In high school, football became his passport to normalcy. Instead of being identified as “the deaf man’s son,” he was known as a football player.

Life as the deaf man’s son carried daily indignities for both generations. One day his father took him to the New York Daily News, where he worked in the pressroom, to show off his son.

To Myron’s face, co-workers would say, “Nice to meet you, kid. How come you can hear?” “How do you like having a deaf father?” “Did your father become deaf because his mother dropped him on his head?”

Behind the boy’s back they would comment, “Look at the dummy’s kid. He looks normal.”

Neighbors were equally insensitive, referring to the family as “dummies” and “the deafies in Apartment 3A.”

But public indignities faded inside the protective walls of their four-room flat, filled with love. Louis bought toys and made four-cornered newspaper hats for his sons.

After dinner, while Uhlberg’s mother, Sarah, washed dishes, his father sat with the two boys at the kitchen table, reading the news about World War II to them in sign. “I could watch the war every night of the week on the human screen of my father’s hands,” Uhlberg writes.

Watching his parents and a group of deaf friends gather every Saturday on a patch of beach at Coney Island, the young Uhlberg was fascinated with the “wild diversity” of their silent language. Men, he observed, signed more aggressively. Shy people made smaller, more guarded signs.

A couple from Georgia signed with a drawl, their silent words flowing “from their hands like syrup, thick and slow.” Together, the friends painted a panorama of word pictures in the air, their hands “fluttering wildly like the wings of a flock of geese taking flight.”

Obsessed with the nature of sound, Uhlberg’s father assumed that colors could be heard.

“What does black sound like?” he would ask. “A hammer,” his son finally responded. “Hard.”

An avid baseball fan, Louis saw parallels between Jackie Robinson and himself. He told his son, “Very hard for a deaf man. Very hard for a black man. Must fight all the time. No rest. Never. Sad.”

Sad, yes. Yet Uhlberg avoids pity or self-pity, interspersing sorrow with humor.

At the age of 9, he faced the ultimate challenge – playing intermediary during a parent-teacher conference. When the teacher explained that Myron was a good student but a severe discipline problem, the mischievous boy signed to his parents, “The teacher says I’m a pleasure to have in her class.”

His father was not fooled.

What shines through this book is the abundant affection and courage that sustained the family through hardships, insults, and shame. Little wonder, perhaps, that when Uhlberg left for college and gave up primary responsibility for his parents, he experienced both relief and an inexplicable sense of loss.

Uhlberg’s poignant story of devotion and responsibility is a love letter of sorts to his late parents. It opens a window into a world of isolation and “eternal silence” unimaginable to most people. Calling sign a language of the heart, he elevates it to something approaching an art form, saying, “It is for me the most beautiful, immediate, and expressive of languages, because it incorporates the entire human body.”

Paying tribute to his father, Uhlberg writes, “I loved the stories his hands contained.” So does a reader, savoring a warm family chronicle as instructive as it is inspiring.

Marilyn Gardner is a Monitor staff writer.