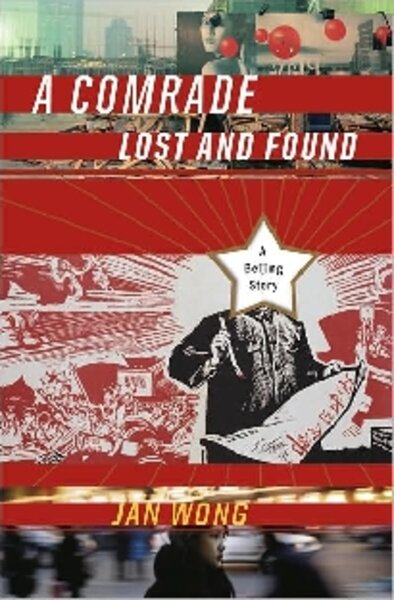

A Comrade Lost and Found

Loading...

In 1973, Jan Wong did a terrible thing. She ratted out a fellow student – perhaps ruining the girl’s life in the process. Then she forgot about the whole thing.

At least, for 21 years she forgot. When she finally remembered, she became obsessed with finding the woman and – if she was still alive and it were possible – making amends. So begins A Comrade Lost and Found, a sharp, keenly observed chase through China’s past and present that somehow manages to be poignant, comic, alarming, and informative all at the same time.

Key to understanding Wong’s story is grasping the fact that she was not malicious. But she was naive. An ethnic Chinese raised in Canada, in 1972 Wong was invited to become one of only two Western students to study at Beijing University.

The country was still in the grips of the Cultural Revolution and Wong thrilled to the ideals of Marxism. Quickly she became enamoured of the idea of China as a workers’ paradise. It did not occur to her that the students and teachers who surrounded her were carefully selected and then coached to conceal from her the country’s ills.

It was only years later that Wong grasped that, “I had been an enthusiastic participant in my own brainwashing.”

While still in thrall to Marxism, Wong was approached by a fellow student named Yin. Yin wanted to go to America and she asked Wong if she could help. Indignant that anyone would want to flee the socialist state that provided a free university education, Wong reported Yin to a party cadre.

Then she went on about her own life.

Fast forward to 1994. Wong is now a journalist finishing a six-year stint in Beijing for Toronto’s The Globe and Mail. She knows China inside out – and she understands China’s history well enough to realize how thoroughly she was once duped.

As she prepares to go home to Canada, she decides to reread diaries from her student days. She stumbles upon her own account of the incident with Yin. Suddenly, she says, “I knew with blinding clarity what I had done. At the age of twenty, I had thoughtlessly destroyed a young woman I didn’t even know.”

At that point, however, Yin seems unfindable. Wong learns that she was expelled from school but after that the trail grows cold.

For a decade, Wong frets over Yin’s fate and then finally realizes, “I’m fifty-three now and I am running out of excuses. It’s time to find Yin.”

So with her husband and two bored teenage sons in tow, Wong sets out for four weeks in China. Her goal is to find Yin and then “apologize and try to make amends.”

Almost nothing could be harder. All Wong has is a name (and even that scrap of information turns out to be uncertain). “How will I find a stranger in a country of 1.3 billion?” Wong wonders. “I have four weeks and no plan of action.”

Her only hope is to return to the people and settings she once knew. She visits Beijing University, meets up with some of her old teachers and fellow students, and asks as many questions as she can.

What she learns is that the Cultural Revolution has become a black hole in Chinese consciousness. There are almost no official records from the period – they either never existed or have since been destroyed.

And when she tries to raise the subject she discovers that most Chinese prefer not to remember too much about what they now call “the decade of disaster.”

“I want to apologize to her,” she tells a former roommate. “No one does that,” the roommate replies. “No one even talks about the Cultural Revolution.”

Answers to Wong’s queries on Yin are maddeningly vague and unhelpful and it’s never clear that anyone is actually telling the truth.

She went abroad, she hears from some. No, she’s back, say others. I see her often, volunteers one former teacher. But there’s no news of her and no way to reach her. “She recently changed her cell phone number,” he insists.

Wong spends much of her four weeks deeply frustrated. (A private detective she considers hiring tells her that, “It’s like looking for her in a vast ocean.”)

Fortunately for readers, however, this waiting period becomes a chance for Wong to share the dizzying disequilibrium she experiences as she chases through a China changing at the speed of light.

Where once Wong bicycled past curving willow trees and sleeping peasants, today an eight-lane highway thunders. The college friend whom Wong fondly remembers preferring a Mao jacket to a sweater (the sweater seemed too flashy) today craves plastic surgery and a top-of-the-line Mercedes.

Wang has a deft touch with an acerbic style of comic writing. She drags her husband and sons through boîtes with names like “Sex and Da City” and past housing developments called “Chateau Edinburgh” or “Rancho Santa Fe.” It’s all brand new, often very ugly, and – in Wong’s hands – quite entertaining.

(One of the devices that ups the humor factor throughout the book is Wong’s penchant for staying straight-faced while using literal English translations of Chinese names. As a result her book is populated by characters with names like Fat Paycheck, Bright Precious, and Spring Plum.)

En route to finding Yin, Wong touches on questions of environmental abuse, religious suppression, lax building codes, and censorship. In other words, it’s a wild ride through the modern Chinese landscape, taken at a gallop.

I won’t spoil the ending by revealing what Wong finally learns about her former comrade. Best perhaps to simply say that, for all of us, life is full of surprises – and that past woes do not necessarily predict the future courses of either nations or their citizens.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor.