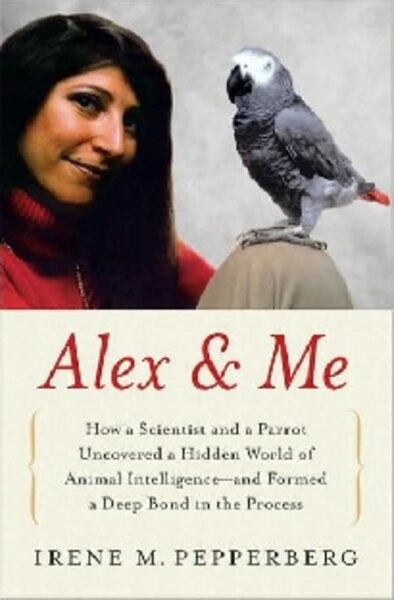

Alex and Me

Loading...

The day that Irene Pepperberg went to buy a bird to use for her experiment in avian language, she was determined to be very objective. So much so, in fact, that she refused to choose the bird herself.

Instead, she asked a pet store employee to pick one of the eight African Grey parrots in his store for her. As Pepperberg recalls in her memoir Alex and Me, the man “picked up a net, opened the cage door, and scooped up the most convenient bird he could reach.”

So began Pepperberg’s life with Alex, the avian genius who would help her to shatter human notions about the limits of animal intelligence.

During his 31 years with Pepperberg, Alex learned the words for more than 50 objects. He could identify seven colors and five shapes. He understood concepts like bigger or smaller, same or different, and he even grasped the more abstract notion of absence or “none.”

He also learned to use words to express his wants and needs, stating clearly, “Wanna go back” when he craved the quiet of his cage, or “Want a banana” when he was hungry. (And if you gave him a grape when he wanted a banana, Pepperberg recalls, he was likely to hurl the grape back at you.)

His feats were featured in magazine articles and on TV and Pepperberg, who is an associate research professor at Brandeis University near Boston and a teacher of animal cognition at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., wrote about Alex in papers presented at academic conferences.

But it was only when he died unexpectedly at the age of 31 (African Grey parrots generally live at least 20 years longer) and tributes sprang up around the world that Pepperberg fully grasped what she and Alex had achieved together.

As Diane Sawyer put it on “Good Morning America” as she announced Alex’s passing, Alex and Pepperberg opened “new vistas on what animals can do.”

It all began, however, much more quietly.

Pepperberg starts her book with her lonely childhood in New York City. Her father was often too busy for her but, fortunately, he did manage to find time to buy her a parakeet. That “little bundle of green feathers” became Pepperberg’s most beloved companion.

As she grew, Pepperberg excelled at school, particularly in the sciences. Eventually she went off to study at MIT, where she shared her dorm room with (of course) a pet bird. Theoretical chemistry became her field and she went on to graduate studies at Harvard.

Then, one night she and her husband saw a television program on public TV about animal intelligence. Suddenly, Pepperberg had a “Eureka” moment in which she knew this was meant to be her field.

But she had chosen a difficult path. At the time, she writes, “received scientific wisdom ... insisted that animals were little more than robotic automatons, mindlessly responding to stimuli in their environments.”

And throughout her career, Pepperberg has struggled both for funding and respect for her work. “You might think that an MIT- and Harvard-trained scientist working at various universities would be given a certain amount of deference, but as a woman working with a bird, I found it was sometimes the opposite,” she writes.

Despite the obstacles, however, Pepperberg spent three decades working with Alex, using a dual-trainer system for teaching Alex (his name meant “Avian Language Experiment”) human language.

It wasn’t all work. Pepperberg and Alex spent eight hours a day together and, as much as she strove for scientific detachment, the two developed a high degree of intimacy. Alex, who had a mischievous, assertive personality, yearned to have his head tickled (and blushed pink when Pepperberg would do so.) He also loved to tear paper, eat cake (which he named “yummy bread”), and dance to The Mamas and the Papas. (He adored classical music as well – only Haydn’s cello concerto could calm him during a storm.)

When Pepperberg acquired other African Greys and began teaching them language as well, Alex became a bossy older brother, shouting out the answers before they could, or admonishing them, “You’re wrong.... Say better!”

Alex died “at the height of his powers,” writes Pepperberg. His powers, apparently, had included his ability – despite her quest for detachment – to win Pepperberg’s love.

“The sense of loss, grief, and desertion that tore viscerally at my heart and soul at the passing of my one-pound colleague and companion of three decades was of a degree and intensity I had never anticipated,” she writes. “I had never felt such pain nor shed more tears. And hope never to again.”

“Alex and Me” may bring you to tears as well but it will also charm and amaze you. As soon as you close its covers you’ll be on YouTube hunting out video clips of Alex at work. For the moment, that’s all we have of Alex – at least, until the next bird comes along able to pick up where he left off.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor.