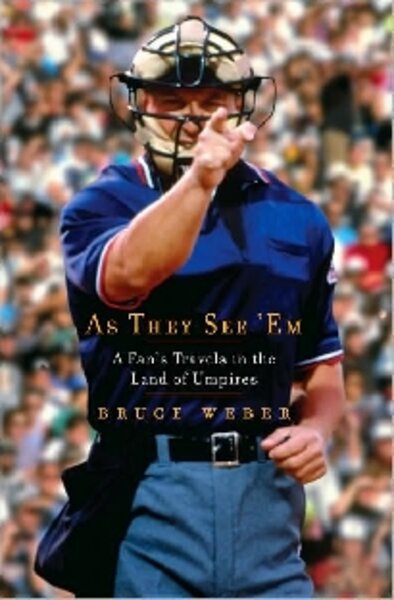

As They See ’Em: A Fan’s Travels in the Land of Umpires

Loading...

It is generally accepted that the best umpires are the ones you never notice. Which may explain why, in the vast and ever expanding literature of baseball, very little has been written about umpires.

They are ubiquitous, but invisible, even when in the thick of the action on the field. Where many players are celebrities, as are some managers, broadcasters, and even a handful of executives and coaches, umpires are almost entirely nameless and faceless.

Eight umpires have been enshrined in baseball’s Hall of Fame. How many fans can name even one?

As Bruce Weber points out in As They See ’Em: A Fan’s Travels in the Land of Umpires, umpires inhabit a parallel universe. On a given play – say a sacrifice bunt with runners on base – they are stationary while the runners and fielders are a frenzy of motion. If the same batter, instead of bunting, hits the ball to the deep outfield, the umpires scramble to get a good look while the players stay put.

Knowledgeable fans analyze, ponder, and consider; umpires are trained not to think, but to react. Players have fans, but umpires are isolated, with no partisans or supporters.

“I feel bad for them,” Jim Leyland, manager of the Detroit Tigers, told Weber. “They’re the only ones in the park who never play a home game.”

Like Margaret Mead among the Samoans, Weber traveled extensively in the “land of umpires” for the better part of three years and consolidated his field notes into an entertaining and highly informative new book.

For five weeks he was one of 120 students at the Jim Evans Academy of Professional Umpiring in Kissimmee, Fla. He visited umpires during spring training in Florida and Arizona, tagged along with two newly minted umps living a hardscrabble life in the low minor leagues, interviewed scores of current and past major league umpires, and even took a crack at umpiring some two dozen amateur youth and adult games.

“You want to know the truth?” he asks. “I didn’t like it. You wouldn’t believe the aggravation.”

It turns out there is a lot not to like. Competition for jobs in the majors is extreme. Only about one in a hundred umpire school students make it to the big leagues.

The pay and working conditions in the minor leagues, especially the low minors, is abysmal. The physical demands of the job are arduous, not to mention dangerous, and the mental pressures intense (Weber devotes most of a chapter to the hazards of umpiring in the glare of the World Series).

Where a player needs only to succeed in hitting the ball every third trip to the plate to be considered very good, the umpire is expected never to be less than perfect. Instant replays and other digital marvels have served to turn legions of couch potatoes into instant experts on the subtle art of officiating a game.

Worse, the umpire’s very workplace is steeped in hostility. Scorn and verbal abuse, including red-faced, nose-to-nose arguments with other grown men, are accepted as part of the job description. Even the lords of baseball aren’t too crazy about them. The owners reportedly regard the umpires in much the same way they regard the bases: as a necessary expense, but not something to which much attention need be paid.

Little wonder that umpires constitute a closed community of martyrs, with an us-against-the-world mentality. At least those who get to the majors make good money, fly first class, and stay in nice hotels.

Weber, a reporter for The New York Times, finds the land of umpires inhabited mainly by working-class men (only six women have umpired in professional baseball, none at the major-league level), mostly white, with a handful of minorities. They tend to be driven and aggressive, goal-oriented and highly competitive. Many take up the profession because of a desire to be around the game. A lot of happenstance also contributes to their career path.

And yet baseball needs umpires, more, I dare say, than most umpires need baseball. Weber sums it up this way: “Baseball ... needs people who cannot only make snap decisions but live with them, something most people will do only when there’s no other choice. Come to think of it, the world in general needs people who accept responsibility so easily and so readily. We should be thankful for them.”

David Conrads is a freelance writer in Kansas City, Mo.