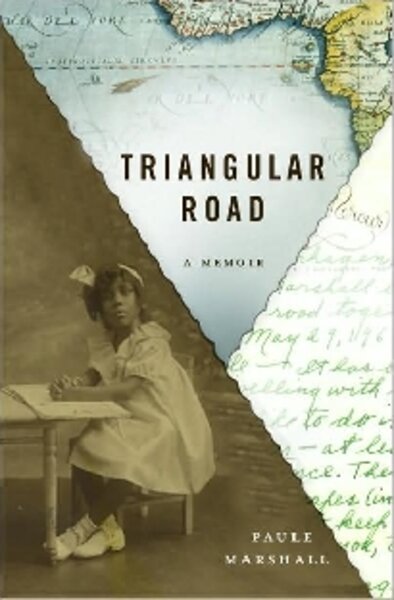

The Triangular Road

Loading...

Paule Marshall is best known as a novelist who explores issues of Caribbean and African-American identity. Throughout a five-decade career she has produced novels like “Brown Girl, Brownstones” and “The Fisher King,” populated with characters inspired by her own experience as the Brooklyn-born child of West Indian emigrants.

Now, she untangles facts from her half-century of fiction, recounting powerful first-hand stories of her family and travels. Ultimately, though, her new memoir, Triangular Road, is at least as much about Marshall’s work as it is her life. The 79-year-old’s approach to her past is a nonlinear collection of essays.

This may frustrate those who expect the biographical breadth of a traditional memoir. But those who can accept her less personal approach will find that parts of this work are as rewarding as a richly drawn novel.

Marshall maintains a certain cautious distance from her readers. She writes poignantly and at length of the slave trade that came through Richmond, Va., for instance – but divulges only a few impersonal comments about her own only child. Her first marriage and eventual divorce warrant a few paragraphs; her second marriage, none. She tells us parenthetically that she decided to change her name at age 13 (she was born Valenza Pauline), but never tells us why.

For selected turning points, though, Marshall provides the illuminating depth that helped establish her fame. She writes of the imposing “M’ Da-duh,” the grandmother she met once at age 7 and immortalized “in one guise or another, in every book I’ve ever written.” Her writing shouts with fury at a one-time editor’s ignorance of an ugly side of Southern history. Even the random woman she once saw on a Barbados road earns a sharply etched place in Marshall’s personal history, sending her on a mental riff to the characters who inspired her second novel.

Marshall’s own story can’t be told, she makes clear, without a larger framework around it. Once she even cures a case of writer’s block by packing away prized notebooks full of factual research, “finally understanding, fledgling that I still was,” that she is a storyteller, responsible first and foremost to the story, and that historical truths will come through if she crafts her tale honestly and well.

Luckily, Marshall is as evocative as a nonfiction writer as she is as a novelist or crafter of short stories. She relies on a descriptive, unhurried delivery that builds up elaborate scenes rather than rushing between plot points. She vividly reincarnates even the rock she once used for a makeshift seat, “a large, somewhat flat stone that calls to mind the oversized ottoman to an easy chair,” lodged under a “canopy-wide willow oak tree that with each breeze seems to transform itself into a huge East Indian punkah fan over our heads.”

“Triangular Road” is adapted from a series of lectures Marshall delivered at Harvard University on “specific rivers, seas and oceans – and their profound impact on black history and culture through the Americas.” It includes an affectionate, still half-awed homage to poet Langston Hughes, an early and steady supporter of Marshall’s work, describing the government-sponsored cultural tour of Europe he invited her to join in 1965.

The book then skips forward to an account of a Labor Day spent by the James River in Richmond in 1998, a city where Marshall gave herself a crash course in “unvarnished” Southern history.

The triangular road of the title, though, is the path of Marshall’s life, which she describes as “a thing divided in three,” between her childhood in Brooklyn, the Caribbean islands that became her on-and-off home, and, in a surprisingly abrupt account at the book’s end, her introduction to “ancestral Africa.”

The book’s soul is Marshall’s description of her childhood in the “tight, little, ingrown immigrant world of Bajan Brooklyn,” particularly her pained, closely observed account of her parents, both born in Barbados and separately making their way to America.

Hearing her mother and friends “ol’talk” in the kitchen, with their Bajan proverbs and colorful stories, she wrote, was her first lesson in the art and craft of writing. She flatly describes her status as “a grievous and permanent disappointment” to her mother, a daughter rather than the hoped-for son, “and one, at that, who was nothing as pretty as her first.”

Her hopeful account of her parents’ courtship, as well as other accounts in the book, are couched in terms of maybes – conversations that might have occurred, emotions that might have been felt. Even her mentor Hughes, she writes, “might have been remembering his own trials and tribulations” as he sat silently, or “might well have been instrumental” in Marshall’s receiving an award for her work, “perhaps recommending the collection” to those he knew on the selection committee.

At first, these suppositions nag like uncut threads. But by the end, drawn in by Marshall’s rich tapestry, it is enough for us to know that this is the story she sees as the best-crafted and most likely.

Rebekah Denn is a Seattle-based freelance writer.