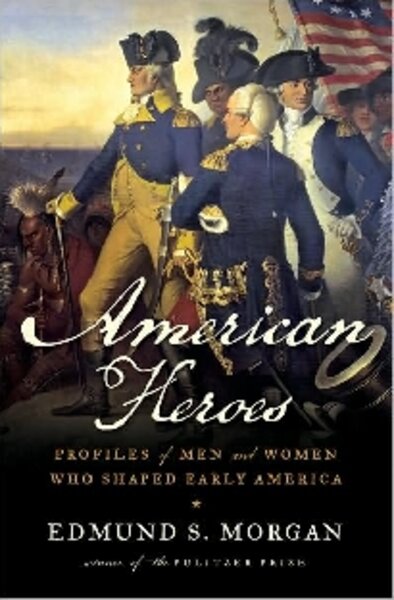

American Heroes

Loading...

Edmund Morgan is a historian – and one of the very best we’ve got. He is the author and editor of more than 20 books, produced over seven decades of scholarship, and is today regarded as a preeminent authority on Colonial America. American Heroes: Profiles of Men and Women Who Shaped Early America is a new compendium of his work, including essays on everything from Columbus’s landing to the Salem witch trials to a piece pondering the relative merits of two early presidents of Yale University.

In lesser hands, a comparison of Ezra Stiles and Timothy Dwight (those two Yale leaders) would hardly feel like a must-read piece. (The two men governed successively more than 200 years ago).

But when Morgan approaches the question, he does so with such curiosity and imagination that the topic feels vibrant and essential.

All historians care chiefly about context, but what makes Morgan’s work unique is that he pursues it along two tracks. He is first an exhaustive primary source researcher. One of the joys of the essays in “American Heroes” is the range of court transcripts, diaries, and letters that Morgan draws on in his analysis.

But Morgan also knows there are limits to what a historian can see if he thinks only about local evidence. In the case of the two Yale presidents, tradition records that Dwight was far more successful than Stiles. Morgan begins his inquiry by reading letters written by Yale College students at the time, and the first one he finds supports conventional wisdom.

Timothy Bishop, class of 1796, writes that “The character of Dr. Dwight is remarkable, he is the most fitted and the best qualified for the instruction and government of this college that could be obtained.”

But Morgan remains skeptical. “Students as a class are surely fickle,” he notes.

Researching further, he finds another letter from Bishop, this one dated three months later, in which Bishop’s enthusiasm has cooled. Bishop’s letters, considered along with similarly vacillating missives from other students, lead Morgan to conclude that historians have been perhaps unduly hard on Stiles and a bit too kind to Dwight.

“The most positive evidence will sometimes take on a different meaning when placed in its proper context,” Morgan writes. In this case, he gets closer to the truth because he considers Bishop both as a student embedded in 18th-century norms and values, and as a universal student, sharing the quality of caprice with all young people of any place and time.

Morgan repeats this creative analysis throughout “American Heroes,” often to delightful and illuminating effect.

In the essay “The Puritans and Sex,” Morgan steps back from the received wisdom about the Puritans (that they were prudes with a delusional view of desire) in order to “listen to what they themselves had to say.”

Consulting letters and sermons from the time, he finds the Puritans frankly extolling the virtues of an active marriage bed. “It is not good that man should be alone,” one minister wrote suggestively. In another case, poor James Matlock was expelled from his church congregation because “he denyed Coniugall fellowship vnto his wife for the space of 2 years [sic].”

The Puritans are among Morgan’s favorite subjects. (He wrote the definitive biography of John Winthrop.) He’s drawn to them in part due to the challenge of parsing the particulars of their worldview from more general characteristics of human beings anywhere.

In “The Puritan’s Puritan” he wonders of the famously priggish Michael Wigglesworth “did [his] concern with other people’s sins represent merely the tedious petulance of a busybody, or was it the expression of some fundamental part of the Puritan belief?”

It is this attempt to sift the universal from the particular that defines Morgan’s work.

He notes, for example, that while Puritan law recommended adultery be punished with death, village libertines were more often sentenced to a whipping, a fine, or symbolic time in the gallows. Such lenience was compelled by the sheer number of adulterers (it would have been impractical to execute them all) and the unrealistic design of the law.

As Morgan puts it, “Though the Puritans established a code of laws that demanded perfection – they nevertheless knew that frail human beings could never live up to the code.”

If there is something missing from much history writing today, it is the very same quality that makes Morgan’s writing so great. He is able to situate the past in dual contexts, both human and historical, and to use each to elucidate the other.

The result is history of a rare kind, written with bravado, intelligence, and imagination.

Kevin Hartnett is a freelance writer in Philadelphia.