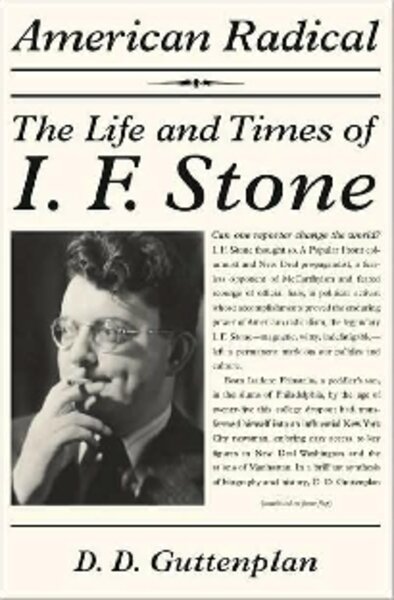

American Radical

Loading...

He was an activist, a radical – an impassioned, indefatigable, zealous idealist – in short, a man who believed that if he tried hard enough he could change the world. Twenty years after I.F. Stone’s death, D.D. Guttenplan offers American Radical: The Life and Times of I.F. Stone, an admiring biography that, fortunately, does not slide into hagiography.

It has only been three years since Myra MacPherson also published an admiring, high-quality Stone biography (“All Governments Lie!: The Life and Times of a Rebel Journalist.”) These two recent biographies of Stone (plus two others since his death) and an accessible anthology (“The Best of I.F. Stone,” 2006) provide a composite view of a journalist whose importance – especially during the current realm of government and corporate corruption and secrecy – cannot be overestimated.

Stone’s close reading of public, but often ignored, government documents as the foundation for his investigative journalism has influenced countless journalists and other researchers.

Born in 1907 and reared primarily in the Philadelphia area, Stone began writing about truth and justice as a teenager. As he matured, his newspaper reporting, magazine writing, book authorship, and public speaking helped to create a well-informed public. But his influence did not reach its zenith until the 18-year period from 1953 through 1971, when his self-published, modest-looking newsletter, I.F. Stone’s Weekly, made an unlikely impact across the nation, with an outsized impact on policymakers in Washington, D.C.

The newsletter gave Stone “a platform from which he [could] rally his fellow heretics, attack their persecutors, and, most of all, encourage resistance,” according to Guttenplan. Stone unmasked the repression of the 1940s and 1950s as symbolized by the lying, hypocritical yet powerful Sen. Joe McCarthy; exposed the government-produced myths of the Vietnam War; showed the thuggery of Soviet Union autocrats; cracked the pristine image of the power-hungry, law-breaking J. Edgar Hoover; shed light on the Israeli and Arab massacres in the Middle East; explained how the tragic meanness against African-Americans throughout the United States could be diminished; shattered the death-defying statements of nuclear-weapons zealots; explained how universal health- care could operate successfully in the nation he loved; and so much more.

Exposing official lies was Stone’s greatest legacy. He did it, however, from a stance of patriotism. He grasped completely that only in a nation with constitutionally based journalistic freedom could a career like his have been possible.

The word “troublemaker” is not often used as a compliment, but Guttenplan offers it as such when he writes that Stone “was a troublemaker all his life.” Amazingly, Stone escaped punishment in the metaphorical principal’s office most of the time. Yes, Stone struggled financially at times because his prickly ways did not always sit well in hierarchical newsrooms, and because trying to support a family on independent newsletter earnings has never been easy.

Still, he achieved notoriety and lived well materially much of his life, supporting his wife and children even while ignoring them way too often because of his long work days. Before his death, Stone became an elder statesman of sorts. Warding off deafness and near-blindness, in his 70s and 80s, Stone taught himself ancient Greek so he could address one of history’s most controversial characters in the learned, gripping book “The Trial of Socrates” (1988).

Biography is a difficult craft, whether the subject is Socrates or Stone. A bonus of Guttenplan’s book is that he confronts the numerous biographical dilemmas within the main text, helping readers grasp the difficulty of determining exactly what is true in any biography.

With Stone, however, it appears that what biographers find in his millions of published words can lead to something resembling truth. Research demonstrates that Stone really was what Guttenplan calls, “an independent radical who kept hold of his ideals, and kept faith with his comrades, without renouncing the freedom to speak his mind.”

It matters greatly, Guttenplan points out. Because the man we find in his words was a remarkable one, indeed. “But grant his credibility,” writes Guttenplan, “grant him the compatibility of his beloved [Thomas] Jefferson and his equally beloved [Karl] Marx – and I.F. Stone remains, even in death, a dangerous man.”

Steve Weinberg’s most recent biography is “Taking on the Trust: The Epic Battle of Ida Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller.”