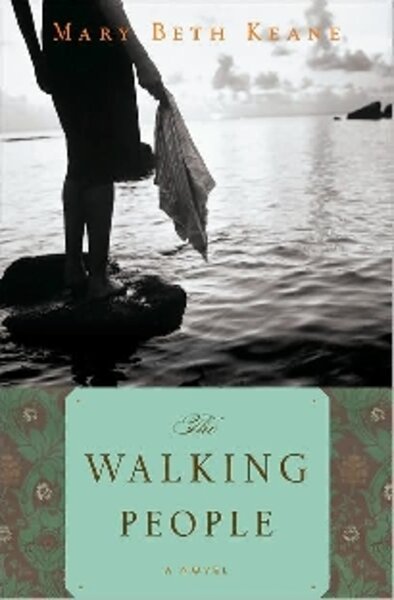

The Walking People

Loading...

This is the era of the immigrant, and if you’re seeking a tale of cultural assimilation, there is no shortage of excellent options. Junot Díaz gives us the jagged edges of the Dominican-American community (“The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao”), Edwidge Danticat writes of the wrenching dislocations of Brooklyn’s Haitians (“Brother, I’m Dying”), Jhumpa Lahiri portrays the suburban discomfort of Indian-Americans (“Unaccustomed Earth”), and Dave Eggers movingly tracks the “Lost Boys” of Sudan (“What Is the What”).

But if, after this multicultural feast, there remains room in your heart for a deliberately paced tale of European immigration, The Walking People, a debut novel by Mary Beth Keane may be your book.

Keane begins her story in the Ireland of 1956 – a land of verdant beauty and almost no opportunity. The Cahill family live in Ballyroan, where the air is whipped with salt, the rivers run silver with fish, and yet no one can make a living. Most of the villagers have already emigrated and so it’s not surprising that Johanna, the Cahills’ feisty elder daughter, wants to join them. But younger sister Greta, a lost, anxious child who spends her life “veering left when everyone else veered right,” seems an unlikely candidate for so large an adventure.

So does Michael Ward. Michael comes from a family of “walking people,” itinerant Irish despised by the rest of their more settled countrymen. Eager to escape the harshness of life on the road, Michael has won a place as the Cahills’ handyman and sees life in the deserted hamlet as the realization of a deep desire.

“All his dreams of settling had looked just like Ballyroan,” he thinks. “Every single thing about the place was right, down to the hawthorn trees and the rushes and the river stuffed with salmon.” But the village is fading and the neighbors are disappearing, and soon the twin forces of economic reality and Johanna’s restlessness have pushed even Greta and Michael onto a steamship heading for New York.

Once they arrive, however, nothing turns out as expected. Greta the goose (as the Cahills call her) begins to thrive, while the more ambitious Johanna stumbles. Emotions splinter and allegiances shift as the sisters scramble to adapt and, before too long, Greta and Michael are a couple with a baby while Johanna has struck out on her own.

There is a more complicated truth, however, to this seemingly simple arrangement, and the train of a shared secret not only drives the sisters apart but also serves to cut Greta off from Ireland altogether. She and Michael eventually add more children to their family and root themselves ever more deeply in the present. It is only in 2007 – as Michael retires – that their fully American children, now adults, eagerly push them back toward Ireland.

“The Walking People” will not be every reader’s cup of tea. Its pace is almost relentlessly low-key and the secret that Johanna and Greta share lacks the heft readers might expect from a novel’s central dilemma. Yet for readers ready to savor the solid comforts of a well-crafted, gently absorbing narrative, this story has much to offer.

Keane creates characters as believable as they are quietly decent and wise. Never heavy-handed, she allows us to journey with them as they slowly accumulate bits of life knowledge: Whether you stay or leave, everything changes. Even when you find a better place, some around you will still long to be elsewhere.

And as Michael, the ex-itinerant, comes to understand and wishes he could have explained to his restless tinker father, “We don’t settle in places. We settle in people.” The understanding that dawns on Greta is even more basic: “Love, it turned out, was disarmingly simple, straightforward.” And so, as it happens, are the muted charms of this thoughtful story.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor.