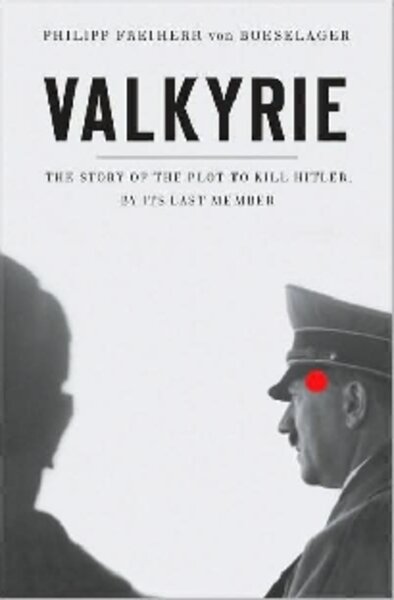

Valkyrie

Loading...

What if Hitler could have been eliminated and his tyranny stopped short? Anyone who has ever wondered will be fascinated by Valkyrie, the posthumous memoir by Philipp Freiherr von Boeselager, the longest surviving member of the assassination plot against Hitler. (Von Boeselager died last May.)

In von Boeselager’s concise account, every sentence contributes to one of two goals: either to educate readers about one of the most important resistance movements of our time or to deepen the understanding of the human lives at the heart of the story.

There are other histories of the conspiracy against Hitler that offer greater detail of the events in which von Boeselager wasn’t directly involved. But in his memoir, with precise language, concrete memory, and impressive metacognitive skill, von Boeselager adds an invaluable element of personal perspective.

The first seven chapters are devoted to background on von Boeselager and his closest brother, Georg. The brothers grew up, joined the Army, and served in France and Russia, even as Nazism was undermining the Germany that their family had loved for generations. Von Boeselager defends German patriotism and separates it from Hitler’s agenda. “We had no more cause to be ashamed of wanting to restore Germany,” he writes, “than had the French who, in 1914, wanted to return Alsace and Lorraine to France.”

Only gradually did von Boeselager become convinced of the need to rebel, he writes. The news of Kristallnacht reached him as a young cavalryman, in his “hermetically sealed” training camp. But this one incident did not indicate to him or his comrades the extent of the criminality taking over their country.

In this respect, von Boeselager insists, he is telling the story of the majority of Germans, who did not “let” Hitler come to power, but who, rather, failed to comprehend the unimaginable in time to stop it. None of von Boeselager’s colleagues were Nazi sympathizers. His interactions with Nazis were always with high-ranking officials and each sped him to the conclusion that Hitler must be assassinated.

A “combination” of experiences led to the difficult decision to commit treason. When von Boeselager was wounded in Russia, he barely survived a deplorable three-week transport to hospital, and was left with “very pessimistic conclusions” about the competence of the military leadership. Finally he met with Nazi officer Erich van dem Bach-Zelewski, who told him of the intentional nature of atrocities carried out by the SS.

Previously, von Boeselager writes, he had imagined these were tragic mistakes made in the confusion of battle. Now he became convinced that the Nazi regime was committing genocide, in addition to killing German soldiers with its hubris and military ignorance. It had to be stopped.

The covertly rebellious von Boeselager was lucky to find himself among like-minded officers in Army Group Center, far from Berlin, on the Russian front. Maj. Gen. Henning von Tresckow, who organized the resistance and drafted the plan called Valkyrie – the system of orders that were to take effect after Hitler’s death – brought Boeselager into the conspiracy and is described with much admiration.

The great achievement of “Valkyrie” is to render a portrait of moral justice within the ranks of the 1940s German Army. Contrary to the common association of the Army with an inhuman regime, “Valkyrie” defends the honor of German military men. Even late in the war, when the military situation portended Germany’s defeat, Tresckow asserted the importance of the plot.

“The assassination has to take place, whatever the cost,” von Boeselager recalls Tresckow saying, “even if it doesn’t succeed, we have to try ... to show the whole world, and history, that the German resistance movement dared to gamble everything, even at the risk of its own life.”

The world’s longing to turn back time on Hitler’s reign of terror is only natural, and it is piqued by the nearness of project Valkyrie’s success – “Valkyrie” reminds us that Hitler was thrice in the presence of bombs designed to kill him, the last of which only missed its mark by a few feet.

But Boeselager’s book doesn’t tarry in the realm of might-have-been. Instead, it explores reality – the importance of making accessible to future generations the full truth of history.

Dan Fritz is a marketing coordinator for the Monitor.