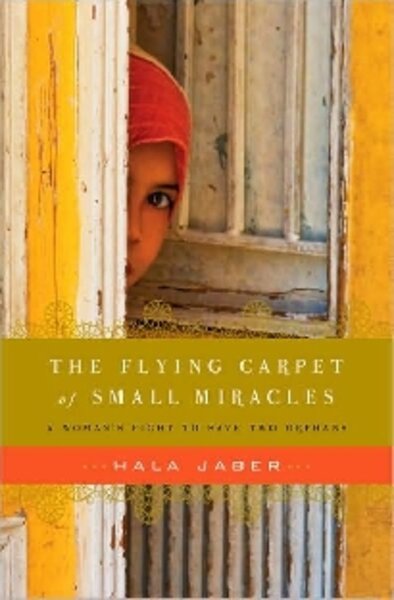

The Flying Carpet of Small Miracles

Loading...

By any measure, Hala Jaber is a courageous woman. An award-winning foreign correspondent, she is one of that rare breed that hastens into the vortex of war, calamity, and danger just as others are rushing out. As a reporter for first the Associated Press and later the Sunday Times of London, she covered Baghdad during the 2003 United States invasion and its aftermath.

Jaber flew in and out of a city under siege, dodged bombs to visit victims, traversed heavily armed neighborhoods, and set up meetings with the sort of shadowy characters from whom most of us would instinctively flee.

But if she developed a rawhide exterior when it came to her professional life, she was anything but hardened in the personal realm. Unable to conceive a child (for reasons that doctors could only label “unexplained”), her unfulfilled desire for motherhood seemed an ever-aching hurt. And when she encountered frightened, injured, and confused children in and around Baghdad, it was all she could do to keep her emotional compass from spinning wildly out of control.

Such is the background and baggage that Jaber brings to The Flying Carpet of Small Miracles, her memoir about covering the Iraq war even as she dreamed of adopting two young orphans she met while on assignment. Hers is an often harrowing tale, but its conclusion offers an unexpected measure of redemption.

As a young woman growing up in a loving Lebanese family, there was nothing Jaber wanted more than to be a mother herself. She was content, however, to postpone that dream while she traveled the globe for her work and married a supportive English photographer. But when she finally decided it was time for children, she discovered that she might never be capable of conceiving.

Heartbroken, Jaber threw herself into her work. Then as the bombs rained down on Iraq in 2003, her editors asked her to look for an injured orphan. Not just any orphan, mind you – but “a wounded girl, between one and five years old, whose parents had died and whose pretty face was more or less unscathed.” It may have been a cynical assignment (photos of beautiful, expressive young war victims sell papers) but Jaber embraced it eagerly. Such photos, she knew, also serve to raise money for victims.

What she found, however, was a pair of orphans – young girls named Zahra and Hawra. Their father (a taxicab driver) and their mother (a homemaker) and their five siblings had all been killed in a missile strike. They were left in the care of their loving grandmother, but Zahra, the older girl, was badly burned and deemed unlikely to survive without massive medical intervention of the kind that she could only get in the West.

Suddenly Jaber had a life purpose. As she fought to get Zahra transferred to a Western hospital (persuading her paper to pick up the costs), she also conceived a desperate plan to adopt both girls and raise them safe in London. Their grandmother, she convinced herself, would understand. Quickly, Jaber allowed herself to be enraptured by her own fantasies, complete with images of cozy domesticity and a pair of safe and happy daughters.

But nothing occurs as Jaber had dreamed, and her struggle to make things right becomes hopelessly intertwined with the sufferings of Baghdad itself.

Jaber skillfully weaves together the different strands of her story. She does not attempt to equate the devastation of war with her own woes. But she does allow a reader to feel the way that one fueled the other in her own experience.

This is a story that brings readers face to face with the horror of war and the suffering of the Iraqis. Sometimes it feels almost unbearable. Fortunately, however, Jaber also writes of the familial love that sustained her and the occasional heroes who inspired her.

Jaber is a deeply emotional person and at times her urgent, desperate quest for motherhood is exhausting. But if she is sometimes grating, Jaber’s conclusion is graceful indeed. “The Flying Carpet of Small Miracles” gives credence to the adage that wisdom eventually comes to those who wait.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor.