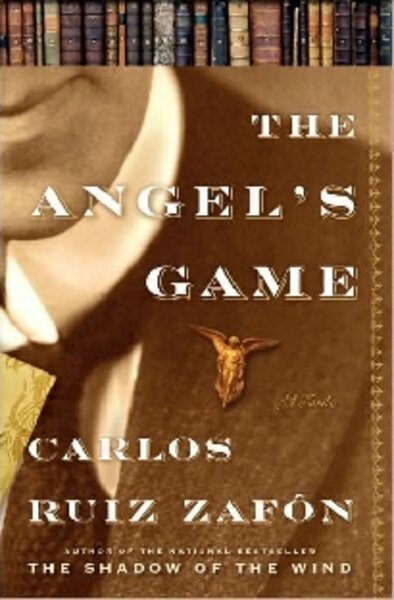

The Angel's Game

Loading...

Carlos Ruiz Zafón specializes in bookworm fantasies. For his breakthrough thriller five years ago, “The Shadow of the Wind,” the Spanish novelist conjured up The Cemetery of Forgotten Books – a vast underground catacomb filled with books that no one alive has ever read. (Here are the keys to my car. Come and get me in a year or so.)

Now, in his sort-of prequel to that bestseller, The Angel’s Game, he offers a Faustian bargain that anyone who ever thought, “Gee, I’d really like to write a book,” would be signing so fast the fine print would be only a blur. For an obscene amount of money, a pulp fiction novelist gets to write a masterpiece that will change the world. Oh, and that nasty brain tumor that’s slowly killing him? Gone.

Of course it’s too good to be true. And David Martín finds himself trying to both meet his deadline and to find out what happened to the last poor sap who signed on to publisher Andreas Corelli’s payroll before he meets the same fate.

(Martín stumbles onto his predecessor’s existence in the Cemetery of Forgotten Books, where a first-time visitor is allowed to choose one – and only – one book. His choice is “Lux Aeterna,” by one D.M.)

But in addition to unexplained corpses, “The Angel’s Game” is brimming with fabulously dry writing advice. “Never underestimate a writer’s vanity, especially that of a mediocre writer,” is one of Martín’s bromides. Another time, when an aspiring novelist comments that “I thought [literature] was something that sprang from the artist, just like that, spontaneously,” Martín remarks, “The only things that spring spontaneously are unwanted body hair and warts.”

(Martín’s a big believer of “squeezing your brain” until it hurts and seeing what oozes out.)

But while Martín might be sarcastic about writing as a career, Zafón is nothing short of reverent about books. “The Angel’s Game” is bursting with homages to Dickens, Defoe, and Dumas, and is the kind of novel where librarians are witty sirens and the good guys are an antiquarian book dealer and a crusty newspaper editor “who did not suffer fools and who subscribed to the theory that the liberal use of adverbs and adjectives was the mark of a pervert or someone with a vitamin deficiency.”

Martín himself is a Pip-like orphan who’s used to having his great expectations dashed and whose mentors may have ulterior motives. He longs fruitlessly for the chauffeur’s daughter of the chief among them, a wealthy scion named Don Pedro Vidal. (Cristina isn’t quite as cold as Estella.) After his pulp career takes off, Martín winds up renting a cobweb-festooned monstrosity that could have been decorated by Miss Havisham. (And somehow, he never finds the time to discover the source of the musty smell in one of the closets – one of a few less than satisfying coincidences.) As his work for the mysterious Corelli progresses, Martín’s misgivings grow right along with the body count.

Zafón, while not entering the realm of metafiction, uses layers of dialogue to create a playful discussion about literature and the value of a good book. When the aforementioned librarian talks about the trouble she’s having with a Gothic plot, Martín’s good-natured suggestion sounds an awful lot like “Angel’s Game.” “I suggested she give it all a slightly sinister tone and focus the story on a secret book possessed by a tormented spirit, with subplots full of the seemingly supernatural.”

The result is a twisty, sarcastic ode to books, with a satisfying dollop of religious theory thrown in for good measure. On its surface, “The Angel’s Game” is a thriller laden with Gothic elements, but readers who need a traditional denouement with answers neatly laid out will come away disappointed. (I definitely had a little moment of “Wait! What? Huh???” at the end.)

But while the plot payoff may not be what readers are expecting, the novel itself is such a pleasure to read that the characters could have ended with a rendition of “The Sun Will Come Out Tomorrow,” played on cowbells and a zither, and I would have shrugged it off.

Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews fiction for the Monitor.