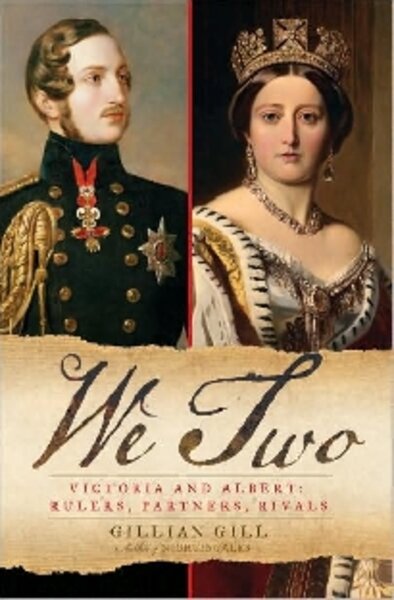

We Two: Victoria and Albert

Loading...

Once upon a time, Queen Victoria was amused. Besotted, captivated, downright smitten even. Her Prince Charming, fresh from a backwater German kingdom, made this hardy monarch go weak at her so-very-British knees.

He was gloriously handsome, deadly serious, and a bit of a prig. She was smart, vivacious, and the greatest catch in all of Europe. United as a royal we, the queen and her prince stood at the pinnacle of the most powerful country on earth for more than two decades, forever in love – and at odds.

It was a most remarkable marriage, and its story is told in a fascinating and tremendously readable double biography.

Victoria and Albert may seem like “unicorns among flowering meadows, irrelevant to our modern world ... but if we listen to their voices up close, we find to our surprise a forerunner of today’s power couple,” writes Gillian Gill in We Two: Victoria and Albert, Rulers, Partners, Rivals.

Gill, who received raves for her biographies of Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy and nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, is an expert at creating vivid portraits from the disparate puzzle pieces of long-ago lives. Here, the historian finds clues to the character of the royal couple in their often-miserable childhoods.

Victoria grew up in isolation, controlled by a devious mother and a high-born henchman bent on gaining power and influence through their child. She only realized her place in the succession at age 11 – famously declaring “I will be good!” – and became queen at 18.

Albert, meanwhile, came of age in the tiny German kingdom of Saxe-Coburg, where the monarchs dismissed morality and monogamy as simply unnecessary. Oddly enough, however, he was raised as an exception to the rule of dissolution as those around plotted to marry him off to the high-minded Victoria.

As an adult, Victoria reigned among powerful men – most notably her husband – who thought women had no business in power.

For his part, Albert was a judgmental moralist who often looked the other way as his own brother led a dissolute life. He criticized his wife for being vain, neurotic, and self-absorbed, “yet, ironically, these were more his faults than hers,” Gill writes.

In some of the most intriguing sections of “We Two,” Gill explores the home lives of those in the English court. We read about chilly castles, endless gossip, and stoic ladies-in-waiting who had to walk backward in high heels and trains to avoid turning their backs on the queen.

In fact, during her whole life Victoria never had to open a door or dress herself. A royal life didn’t translate into a happy one, however: Victoria and Albert were destined to spend much of their lives with few if any friends, and “the intimate friendship they had for each other could not quite suffice.”

But they made do with their relationship, and it was one for the ages. A bounty of letters between Victoria and Albert help Gill to examine their marriage in depth, and she finds signs of their deep physical connection in the words of a woman whose supposed Puritanism gave the name to an entire age. Victoria herself wrote that she “felt, when in those blessed Arms clasped and held tight in the sacred hours at night, when the world seemed only to be ourselves, that nothing could part us. I felt so v[ery] secure.”

Gill goes a bit overboard with her speculation about their wedding night, but fortunately her theories about the emotional lives of the royal couple are anchored in reality, not psychobabble.

Over time, their dynamic became volatile, pushing them into parts in a play: the preoccupied, distant husband and the unappreciated, nagging wife. “From the beginning, she had been the lover and he the beloved,” Gill writes. “As time went on, her love and need for him only grew, while he seemed to feel her love almost as a burden.”

Gill could have spent a few more pages examining how the queen and prince handled the social and geopolitical issues of their day. But she does reveal Albert’s brilliant editing of a note that helped avert catastrophic British involvement in the American Civil War.

“We Two” ends not long after the agonizing death of Albert. He passed away in his early 40s and left his wife to reign alone. She found new men to provide companionship, if not physical intimacy, and devoted herself to preserving and whitewashing her husband’s reputation, creating ever-lasting myths that stubbornly refused to vanish until now.

We can see them both more clearly thanks to Gill’s perseverance as a scholar and skills as a gifted writer. A committed and endlessly complicated couple, they indeed seem as if they’re products of our own time. At the least, they still have much to teach us after all these years.

Randy Dotinga is a freelance writer in San Diego.