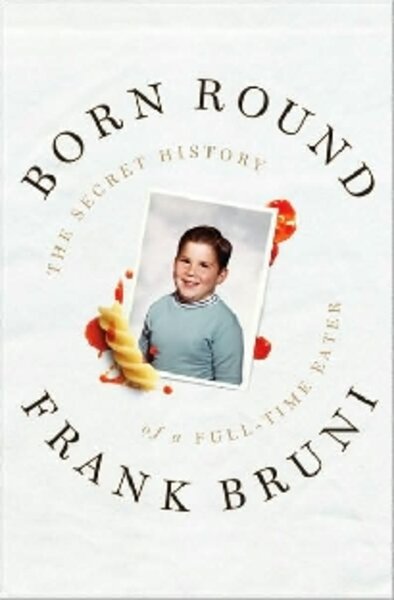

Born Round

Loading...

Frank Bruni’s memoir is all about food – and yet not in the way most readers would expect. Bruni, who just left his post as restaurant critic for The New York Times, does devote a small slice of Born Round to the glamorous attractions of the critic’s life.

He delivers some restrained dish on the territory immortalized by another former Times critic, Ruth Reichl – the credit cards issued under false names and the wig he wore for one review, the crab consommé and the potato-crusted cod.The book’s unflinching focus, though, is on Bruni’s lifelong love-hate battle with overeating. The meat of the story, rather than luxe dinners, is his bingeing journey through bulimia, speed, Metamucil, crash diets, and other ways he fought to control his weight from childhood onward. Food is also the heart of the book’s candid and loving account of his family life, an Italian grandmother who saw food as “a currency and a communicator like no other,” a mother who made turkey sandwiches as a shorthand message that “she was rooting for, and watching over, me.”

Bruni is entrapped in a “tropism toward calories,” and every life event is a thread in that web. The 2000 presidential campaign, which he covered for the New York Times, is a siren song of overwhelming stress and bad food, a hotel buffet giving off “the heady, greasy, piggy perfume of an unhealthy breakfast for the taking.” He writes a book, and feels compelled to digitally distort his author’s photo to appear thinner. He takes on a new posting in San Francisco, in part, in hopes it will catalyze him to exercise.

By the time Bruni explains to a friend that he is declining a date because he can’t delay it long enough to lose a few pounds, we welcome her bemused response: “You do know, by the way, that the company medical insurance provides partial reimbursement for therapy?”

“Born Round” keeps the reader engrossed, though, also rooting on Bruni’s team and touched by his struggle. That is partly because, after all, he is a talented storyteller – famed, he tells us, for what’s known in the newspaper business as good color. He writes, for instance, that his extended breakup with a boyfriend “put me off the very idea of sex or romance the way being stung by a jellyfish puts a toddler off the ocean.”

But the book mainly wins readers because of Bruni’s enlightening, painfully sharp perceptiveness. He has worked through most of the insights that a therapist might bring; he is aware of the self-deluding part of the brain that “keeps your disappointment in yourself at a manageable level”; he sees “a strange mercy in being fat,” an easy scapegoat for all his problems.

Bruni’s all-encompassing relationship with food, familiar to many women, is rarely heard from a man’s perspective, a fact a less personal book might research more deeply. He does wonder if he and his sister (though not his brothers) share the struggle because both seek out men as romantic partners, and American culture demands that “if you wanted your pick of men, beauty was your best weapon, and beauty began with thinness.”

He is refreshingly human in his ascendancy to restaurant critic, feeling that his reporting abilities and enthusiasm would make him “a better proxy for consumers” than a critic more immersed in the culinary world. (Bruni may be the only veteran of the post to admit to scarfing precooked Tyson chicken parts and Nutter Butter cookies.) And the job, which seems so ironic given his history, proves to be “the ultimate dare” once he masters his weight and his demons, as he ultimately does.

The book will speak to anyone who has taken a full pint of ice cream from the freezer and eaten it to the bottom, anyone who has burned with self-loathing while throwing the container in the trash. Those numbers encompass a far greater audience than just avid foodies.

Rebekah Denn writes at www.eatallaboutit.com.