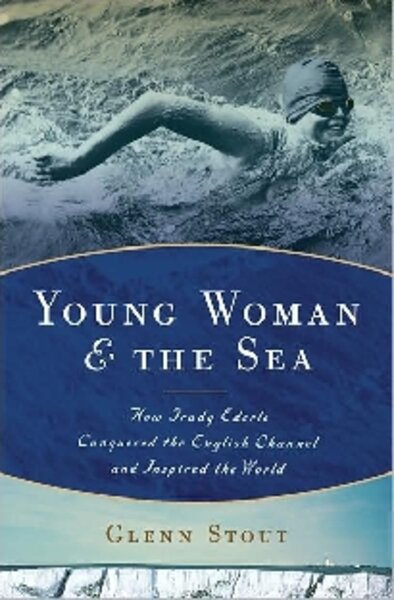

Young Woman & the Sea

Loading...

It’s hard to imagine a time when the Summer Olympics didn’t conjure up images of sharkskin-clad, chiseled athletes. Michael Phelps drew 31.1 million viewers in his hunt for eight gold medals in 2008. Dara Torres inspired countless middle-aged athletes when she captured the silver in the 50-meter freestyle at the same Olympics at the age of 41.

It wasn’t so long ago, however, that the thought of surviving in water – let alone swimming – invoked fear and trembling among ordinary citizens. Not until the turn of the 20th century did organized swimming take shape, and largely in response to the frequency in which people were drowning in open water.

The Manhattan Women’s Swimming Association (WSA), founded in 1917, aimed to teach women and children how to swim. And one of those youngsters was Gertrude “Trudy” Ederle of Atlantic Highlands, N.J., would not only go on to become one of the globe’s fastest swimmers but also the first woman to cross the English Channel. Glenn Stout does a masterly job of re-creating her feat in Young Woman & the Sea: How Trudy Ederle Conquered the English Channel and Inspired the World.

Ederle’s story mirrors a churning surf with its unpredictable rises and falls in athletic achievement; its massive public interest, which again and again vanished like a wave upon sand; and an ever-present silence. The young swimmer had lost most of her hearing in a bout of early childhood illness. Social encounters outside her large family, who were of German descent, were awkward and trying. She frequently misunderstood what was said to her and spoke too loudly in response. Swimming for hours on end became Ederle’s natural escape, a submerged world where she was neither required to hear or be understood.

Stout thoroughly presents several historic developments that were occurring as the reclusive teenage Ederle was gradually recognized as a standout swimmer in open-water races. One was the development of the American crawl, an overarm thrashing stroke known today as freestyle. Another was an expanded view of what women could achieve as women’s rights organizations grew more vocal and groups such as the WSA started producing results (in this case, exceptional swimmers). Further, the end of World War I left the public hungry for entertainment. “With the possible exception of the speakeasy,” writes Stout, “spectator sports suddenly became America’s favorite pastime.” And the English Channel itself, now freed from battleships, had become a stage upon which swimming adventurists tested their mettle – and upon which Ederle was the first to prove the strength of her sex.

Stout carefully plays out these forces so that by the time we are trailing Ederle in a tugboat from France to Dover the weight of her achievement and the world’s thundering response provoked a stream of tears from this reader.

It came as a bit of a surprise in the summer of 1922 when the previously unremarkable 15-year-old Ederle trounced the best female swimmer in the world, Hilda James, in an unexpected win in a long-distance race along Manhattan Beach. Despite the wind and rain that day, Ederle swam with utter enjoyment, thoughts of herself forgotten. “It was that simple. The other girls swam to get back to land, but Ederle swam, well, to get away from everything, and in doing so, out in the water, she found her own true self, the place where she felt most comfortable, where she did not think or worry but simply felt the water holding her up and pushing her along.”

Now, with the attention of her WSA coaches, Ederle turned toward mastering races in pools. Swimming her same, even stroke, whether in a 50-yard or 1-mile race, Ederle began to break record after record with the steadiness of a steamship vessel. Over the course of the next two years, Ederle’s dominance in the water held. As she bore down on the 1925 Olympics in Paris there was little doubt she would come home with gold hung around her neck.

But the Olympics became her greatest disappointment. “Agony” is the simple title of the chapter in which Stout chronicles the devastating results of Ederle’s performance due largely to lack of swimming facilities to maintain her fitness, poor nutrition, and crude housing and transportation in the days leading up to her events. Instead of gold, she came home with bronze in the 100- and 400-meter races.

For a time, her swimming career declined. Life after the Olympics “was like diving into a pool and finding out it was filled with only a foot or two of water.” Yet it wasn’t long before crossing the English Channel captured her imagination. She first sought the tutelage of an ornery Scotsman, Jabez Wolffe, who was obsessed with the Channel after his own failed two-dozen attempts to cross it. But their partnership was unpleasant from the start and resulted in an aborted Channel crossing attempt, and accusations that Wolffe had undermined Ederle’s efforts.

For her second attempt, Ederle and her father hired Wolffe’s competitor, Bill Burgess, the second man to swim the Channel, after Matthew Webb. It was under Burgess’s careful coaching and discernment of the tides, weather, and course that Ederle climbed from the sea onto England’s shores on Aug. 6, 1926, at 9:40 p.m. after 14 hours and 31 minutes, “more than two hours faster than anyone had ever done so before.”

In one of Stout’s more captivating passages, he recounts the drama that was being played out in the tugboats that carried Ederle’s father, sister, and coach, and reporters. As the weather worsened, Burgess began to fear for Ederle’s well-being even as she neared her goal. Her father, determined that another misguided coach not thwart his daughter’s efforts, held firm. Ederle would keep going. But someone finally called out, “Come out, girl, come out of the water!” Ederle, who somehow heard this plea above the engine of the accompanying boats, the whoosh of the waves, and through her thick cap, paused. “What for?” came her response, as she redoubled her efforts to swim toward England and into the history books.

The world responded with such a wave of interest and enthusiasm that Ederle, thronged by the press, was left utterly exhausted. A ticker-tape parade welcomed her in New York and thousands of fans trailed her every movement. But within weeks, it was over. Mille Gade Corson quickly became the second woman to cross the Channel, and even though Ederle’s record time held, by the end of August that, too, was gone, broken by Ernst Vierkoetter, who shattered Ederle’s record by nearly two hours.

For many swimming pioneers, once their remarkable feat had been achieved, there was little left besides strange exhibition tours that involved swimming in glass tanks and giving speeches. The same was true for Ederle. Her hearing eventually deteriorated completely and she lived out her life quietly and unremarkably, never marrying, and finally passing on in 2003 at the age of 98.

But in her wake has come a legion of women athletes unyielding in their efforts to push the boundaries of age and experience.

“Trudy didn’t need to be there for that to happen, at the front line, breaking down the doors herself time and time again, because she had already blown them away,” Stout writes. “All other women needed to do was force their way through the opening, to follow Trudy into the water, and when told they should stop, ask ‘What for?’ themselves.”

Indeed, whatever for?

Kendra Nordin is a Monitor staff editor.